Is the Iran nuclear deal dead and buried?

- Published

The Iran Nuclear Deal explained

In theory, the Iran nuclear deal is still in existence. But only just.

The country has announced that it will no longer be bound by any of its restrictions in terms of the numbers or type of centrifuges that can be operated or the level of enrichment of uranium that it can pursue.

But Tehran insists that all of the steps it has taken to breach the agreement - formally called the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) - are reversible. Other parties have to honour its terms, which presumably means that the US must abandon its crushing economic sanctions and endorse the deal once more.

It is very hard to imagine President Donald Trump abandoning his "maximum pressure" campaign and lifting the sanctions, so that may well be a non-starter.

At the very least, the Europeans must find some payment mechanism to make up for the damage that is being done to the Iranian economy. They have tried to do this but so far to no great effect.

Governments can posture from the sidelines but it is up to individual companies to decide if they want to trade with Iran and risk the weight of US sanctions. The evidence so far is that they do not.

So is the nuclear agreement dead and buried, or could it be revived? If it is well and truly defunct, then why not simply acknowledge this fact? And who exactly killed it?

The last question is the easiest to answer. For in a purely technical sense, looking at the agreement and its implementation, the Iranians have a point when they blame the US.

The deal has effectively been on life support ever since the Trump administration abandoned it in May 2018. Donald Trump has consistently railed against former President Barack Obama's "bad deal". But all of its other signatories - the UK, France, Russia, China, Germany and the EU - still believe it has merit.

The JCPOA was never designed to be a perfect deal - there is no such thing. Its purpose was to constrain Iran's nuclear programme for a set period in a largely verifiable way.

Iranian President Hassan Rouhani (R) previously threatened to restart uranium enrichment

There was a hope that as economic benefits came to Iran, its wider disruptive policies might change. By the time the constraints of the agreement finally expired, perhaps there would be an altogether different Iran from the one we know today.

But the deal's main rationale - a particularly significant one given the current crisis - was that it helped to avert war. Before its signature, there was mounting concern about Tehran's nuclear activities and every chance that Israel (or possibly Israel and the US in tandem) might attack Iran's nuclear facilities.

Iran has always insisted that it does not want the bomb. But at one point it certainly had a military nuclear programme. The specifically military aspects of its nuclear programme were halted some time ago, but its enrichment effort, the hardening of its facilities against attack, and its developing missile programme, all stoked fears that Tehran would one day get to a point where it could "break out" and dash towards a bomb.

The whole point of the 2015 deal was to make this "break-out" time sufficient to ensure that any military-related activities would be spotted in time for international action to be taken.

The deal went into force. But then along came President Trump and he wanted the agreement gone. Sanctions were re-imposed. Iran condemned this as a breach of the whole deal and thus determined to take action itself.

It should be noted that prior to the US withdrawal, the international nuclear watchdog, the IAEA, was clear: Iran was living up to its side of the bargain.

Since the US withdrawal, Iran (albeit after some delay) has successively breached some of the key constraints of the deal. Now it appears to be throwing these constraints over altogether. What matters now is precisely what it decides to do.

Will it up its level of uranium enrichment to 20%? This would significantly reduce the time it would take Tehran to obtain suitable material for a bomb. Will it continue to abide by enhanced international inspection measures?

Much has been made in Washington of Iran's wider regional behaviour. Signing the nuclear deal made no difference to this. Indeed, the initial relaxation of sanctions may have provided funds for Iran's expansive regional campaign of influence.

But that is not what the agreement was designed to constrain. It was a nuclear agreement alone and according to most of its signatories it was working up until the US walked away.

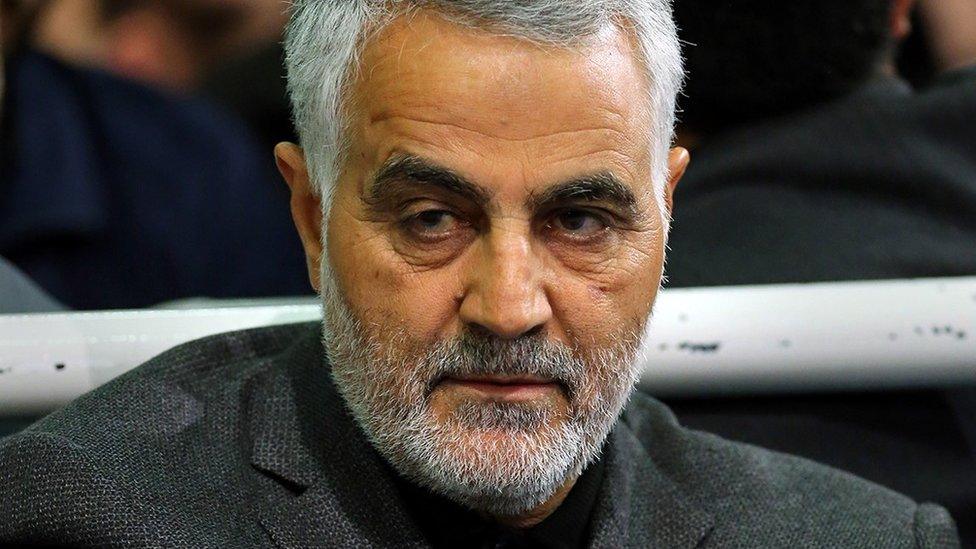

We are now at the destination the Trump administration clearly hoped for in May 2018. But the major powers, while deeply unhappy about Iran's breaches of the deal, are also shocked at the controversial decision by Mr Trump to kill the head of Iran's Quds Force - a decision that has again brought the US and Iran to the brink of war.

The tensions between the US and many of its European allies complicate things no end. Nobody other than President Trump wants to declare the agreement dead. Once it is gone and Iran is breaching its terms, the Europeans will have to decide whether to renew nuclear-related sanctions themselves.

Accepting the deal's demise might make a difficult situation even worse and Iran clearly sees value in holding to the empty shell of the agreement - a least, to differentiate itself from Washington.

- Published3 January 2020

- Published3 January 2020

- Published16 November 2021

- Published23 November 2021