Iran nuclear deal: Shadow of sabotage hangs over critical talks

- Published

The US and Iran are talking in Vienna through intermediaries

A shadow war between Israel and Iran hangs ominously over the resumption of critical talks in Vienna on Wednesday, aimed at returning Iran and the US to the 2015 nuclear agreement.

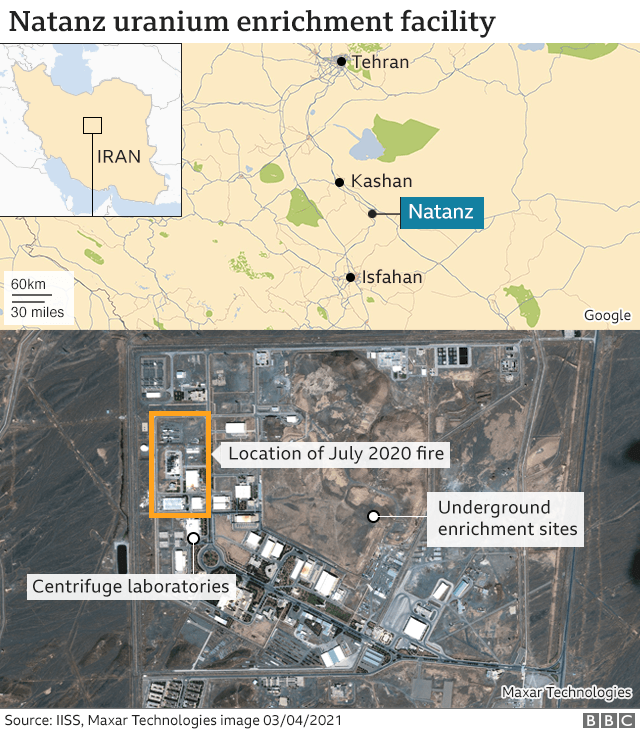

The talks come just three days after a sabotage attack at a key Iranian nuclear plant near Natanz, where an explosion cut off electricity to the whole site. The attacked damaged an unknown number of centrifuges - sophisticated machines that make uranium usable for nuclear purposes - and has stopped work at the facility for now.

A day earlier, President Hassan Rouhani had officially opened an assembly plant at the site, designed to develop centrifuges which can work much faster. The old assembly plant was mysteriously blown up by unnamed "enemies" in July last year.

Iran's nuclear programme: What's been happening at its key nuclear sites?

Israel's Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu has said a return to the 2015 nuclear deal is an existential threat to his country, which Iran considers its arch-foe. Speaking last week on the eve of Holocaust Remembrance Day, he said Israel would defend itself with its own resources.

In Vienna, the latest sabotage attack, which Iran described as "nuclear terrorism" and for which it blamed Israel, is a reminder to all sides that there is urgency, and that any outcome of the talks will have to satisfy not only Iran, the US and other world powers, but also Israel and Iran's neighbours.

The attack has also blown a hole in Iran's negotiating strategy of rapidly expanding its nuclear programme to gain leverage at the talks.

Iran nuclear crisis: The basics

World powers don't trust Iran: Some countries believe Iran wants nuclear power because it wants to build a nuclear bomb - it denies this.

So a deal was struck: In 2015, Iran and six other countries reached a major agreement. Iran would stop some nuclear work in return for an end to harsh penalties, or sanctions, hurting its economy.

What is the problem now? Iran re-started banned nuclear work after former US President Donald Trump pulled out of the deal and re-imposed sanctions on Iran. Even though new leader Joe Biden wants to rejoin, both sides say the other must make the first move.

In response, Iran announced that as of Wednesday it would increase its enrichment of uranium to a significantly higher level of 60% purity - a step closer to the 90% needed for a nuclear bomb, something Iran says it is not seeking. The announcement threatens to derail the talks: such a step is a serious proliferation risk which is not acceptable even to Iran's allies, China and Russia.

The talks are aimed at bringing Iran and the US back into compliance with the deal, which would mean putting a stop to Iran's march towards advanced nuclear capability, and the lifting of US sanctions that have crippled the Iranian economy, hitting a nation of nearly 85 million people hard.

Shuttle diplomacy

The talks are being held between the US and Iran indirectly, with Britain, France, Germany, Russia and China acting as conduits under the chairmanship of the EU. The Iranian delegation is under strict orders from Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei not to talk to the US face-to-face.

The Iranian and the US delegations are holed up in separate hotels that are situated about 100m (330 ft) across the street from each other. The EU's deputy foreign policy chief is doing the shuttle diplomacy. Valuable time is being wasted, say American officials who remain open to direct talks.

Donald Trump pulled the US out of the deal, which he said was flawed

Last week, all sides agreed to the establishment of two working groups of experts to hammer out exactly what steps Iran and the US will have to take to return to compliance with the 2015 deal. Former US President Donald Trump abandoned the agreement in 2018 and Iran has increasingly breached it since then.

The administration of President Joe Biden, Mr Trump's successor, has said it is willing to go back to the accord and lift nuclear-related sanctions only when Iran returns to the strict limits set out for its nuclear activities under the deal.

Iran on the other hand, according to the Supreme Leader, will only honour the agreement once the US has verifiably lifted all sanctions.

More than 1,500 sanctions were imposed on Iran after President Trump withdrew from the agreement, many of them related to Iran's nuclear activities. But a good number are also related to other issues - from alleged terrorist activities, to human rights violations, to Iran's support for militias in neighbouring countries, and Iran's development and testing of ballistic missiles.

Iran insists that many of the US sanctions under different headings are in essence nuclear-related and will have to go.

As for Iran rolling back its violations of the deal, President Rouhani has said this would take no time at all, and that it would be a matter of loosening a few screws and tightening a few more. The signs are, though, that it is much more complicated than that. The head of Iran's Atomic Energy Organisation, Ali Akbar Salehi, has said the process could take two to three months.

Looming 'deadline'

And then there is the question of whether 2015 deal is still as robust an agreement as it was when it was signed six years ago. A lot of water has passed under the bridge, according to the UN atomic energy agency.

"I cannot imagine that they are going simply to say, 'We are back to square one', because square one is no longer there," IAEA Director General Rafael Grossi has said.

In the past two years, Iran has developed, tested and installed new, advanced centrifuges that have altered the calculation on which the limits set by the 2015 deal was based.

Ahead of these talks, President Rouhani made it clear that ending the US sanctions against his country would be a top priority in the four months that is left of his government. Presidential elections are due on 18 June and President Rouhani will hand over to the new government on or around 5 August.

This creates a psychological deadline for the talks to produce results, as signs are that the elections will return a hardline president - most likely a former, or even a current, member of the ideologically-driven Revolutionary Guard.

The general view, both in Tehran and in Washington, is that with the new government in Tehran it will be much harder to resolve the nuclear issue. The hardliners in Tehran are concerned about the haste with which they say President Rouhani has embraced the talks in Vienna - talks that they say will again sell out Iran's nuclear achievements - just like in 2015.

Related topics

- Published12 April 2021

- Published16 November 2021

- Published19 February 2021

- Published19 January 2021

- Published12 April 2021

- Published6 April 2021

- Published4 January 2021