Iran's presidential election: Four ways it matters

- Published

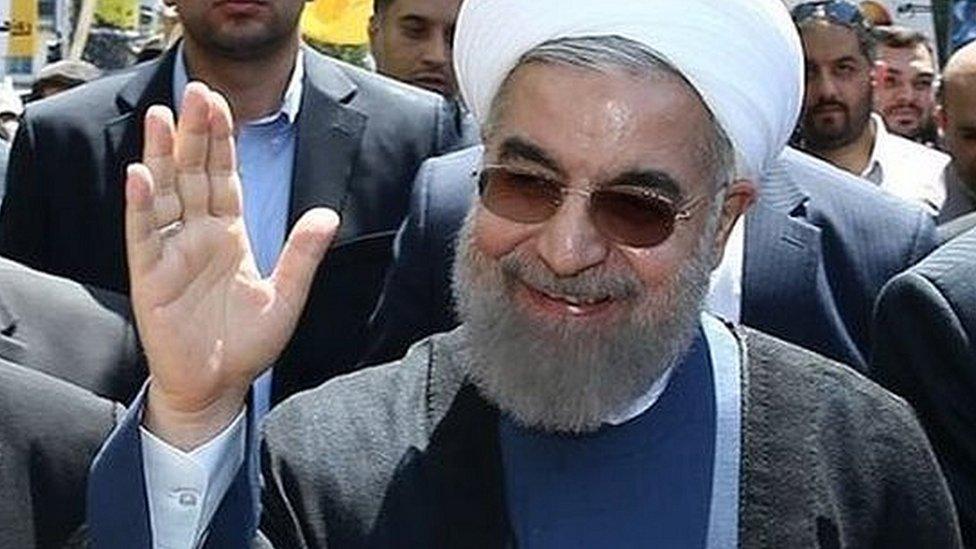

Most of the candidates who have been allowed to stand are hardliners

Iranians are due to choose a new president this month at a pivotal time for the country, both at home and abroad. Much has changed in the four years since the last election - and here are key reasons why this one will be closely watched.

Growing dissatisfaction

Since the last presidential election in 2017, a series of events has drastically changed the Iranian political landscape. They include deadly crackdowns on anti-government protests; arrests of political and social activists, executions of political prisoners; the shooting down of a Ukrainian airliner by Iran's Islamic Revolution Guard Corps (IRGC); and a severe economic crisis as a result of US sanctions.

The repercussions among ordinary Iranians are having a significant impact on the upcoming election. Perhaps the most substantial blow to Iran's rulers would be low voter turnout, as dissatisfaction among the electorate is at its peak.

The cost of living in Iran has soared since the last election

Although it is widely believed that Iranian elections are by no means free and fair (mainly due to the vetting of candidates by a hardline body known as the Guardian Council), Iran's leaders still need high turnout to prove the legitimacy of the political system. It is this legitimacy that has been seriously challenged by the events of the past four years.

However, polls by the government-aligned Iranian Students Polling Agency (Ispa) show a 7% drop in expected turnout to just 36% since the list of candidates was announced on 25 May, while the hashtag "No Way I Vote" is now a trend on Persian social media.

In previous elections, low voter turnout has usually given the upper hand to the hardliners and conservatives.

All eyes on hardliners

Since 1997, presidential elections have been polarised, with contenders belonging to hardline and reformist/centrist factions.

But a recent directive from the Guardian Council practically barred most reformist or centrist candidates from standing this year.

Out of tens of prominent political figures who registered, only seven were approved by the council. Just two of the seven are reformist/centrist candidates, and both are considered low profile.

Ebrahim Raisi is considered the favourite to win

Iran's judiciary chief, Ebrahim Raisi, who was the runner-up in the 2017 election, is the best-known contender, and according to some state polls he is the favourite candidate among the hardliners.

Some observers believe the others who have been allowed to stand are only really supporting candidates to help Mr Raisi's bid.

Economy in crisis

The economy has always played a key role in the Iranian elections and it is high on the agenda of every candidate. Due to the precarious economic situation, Iran is now in one of its most critical phases since the 1979 revolution.

The impact of sanctions, exacerbated by the coronavirus pandemic, has caused one of the worst economic crises in the country's history, with the inflation rate reaching 50%.

BBC Monitoring's Kian Sharifi explains why Iranians have been queuing for chicken

When the government arbitrarily increased the price of petrol in November 2019, thousands of people took to the streets in more than 100 cities.

According to Amnesty International, within a few days more than 300 unarmed protesters were killed by security forces. Protesters demanded the resignation of members of Iran's ruling elite and the government. Similar protests could erupt again.

Rare anti-government protests were held across the country in 2019

Although many believe that radical change is necessary and only possible through protests and strikes, there are those who believe that gradual change is more peaceful and feasible through the ballot box.

The political climate is volatile and things can go one way or another, right up to election day.

Relations with the US

The victory of Joe Biden in the 2020 US presidential election raised the prospect of reviving diplomatic negotiations with Iran, after tensions between the two countries soared under his predecessor Donald Trump. Although most hardliners within Iran's political establishment regard talks with the US as pointless, reformists and centrists are in favour.

Tensions between Iran and the US have deepened in recent years

The latter two also support joining international anti-money laundering organisations such as the Financial Action Task Force (FATF), reconciliation with regional rival Saudi Arabia, and reducing rhetorical aggression towards Iran's arch-foe Israel.

Such measures would significantly reduce friction in the region and also create an opportunity to revive Iran's ailing economy.

However, as the overall policies of the Islamic Republic, including its foreign policy, are determined by the Supreme Leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, those who intend to boycott the upcoming election believe whoever is the next president has little power to change the status quo without his consent.

And even then, normalising relations with the US or recognising Israel as a state is currently unthinkable.

Related topics

- Published20 May 2017

- Published30 April 2021

- Published29 April 2021