Karachi's tit-for-tat ethnic river of blood

- Published

At least 40 people died in violence that started on the eve of a hotly-contested election

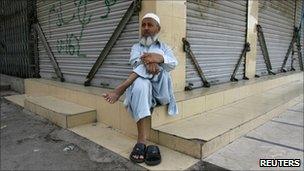

The shutters are down and the gates are padlocked at the spare-parts market in the southern Pakistani city of Karachi.

Thirteen people - shopkeeper and customers - were shot dead here in cold blood on 18 October.

But the massacre was not the work of criminal thugs or self-styled Islamic holy warriors.

It began as a turf-war between two political parties, but has evolved into tit-for-tat ethnic cleansing.

Imran, a shopkeeper, escaped the slaughter by hiding in his shop when the shooting started.

But not everyone was so lucky: Imran heard his neighbours - Anees Rahman and his two sons - being gunned down.

"They also tried to hide inside - but the gunmen saw them," said Imran.

"Mr Rahman made his sons stay inside the shop and came out himself to negotiate with the men.

"He said, 'You have me; let my sons go.'

"But the gunmen shot him and then pulled up the shutters and opened fire."

Imran and all other eyewitnesses to whom the BBC spoke at the Rahman family funerals were in agreement about the gunmen's identities:

"They were Baloch and they came from Lyari," Imran said.

"I heard them asking, 'Who is Urdu-speaking here?'"

The Rahmans, along with the rest of those killed, belong to the Urdu-speaking community.

The mourners were peaceful, but they were also angry at the government.

"The government has failed to keep the peace in Karachi," Asim, a mourner, told the BBC.

"If they can't deal with these people, they should give us a free hand. We will take care of them ourselves."

Politician murdered

The shootings at the Shershah market, which sells mainly mechanical parts, followed two days of targeted attacks.

At least 40 people died in the violence, which was prompted by a Karachi by-election

At least 40 people died in the violence, which started on the eve of a hotly-contested election and culminated in the Shershah market slaughter.

The vote was for a seat in the provincial parliament, after the former incumbent was murdered in August.

The MQM political party, which dominates Karachi, won the election, as expected.

It is supported by the city's majority Urdu-speaking community.

Their rivals in the campaign were the ANP, which is dominated by Pashtuns.

Pakistan's ruling PPP political party decided to back the ANP in the poll.

Partners and enemies

The ANP and MQM are minority partners in the PPP-run central government.

But in Karachi, the two parties are sworn enemies.

Each side accuses the other of killing rival party activists.

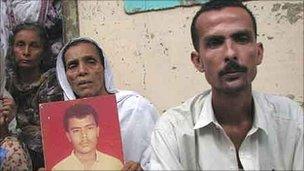

Jaan Bibi's son, an ethnic Baloch, was shot dead in retaliatory killings after the Shershah market attack

It's not just the Urdu-speaking community that has been targeted.

In fact, most of those killed belong to the Pashtun and Baloch communities.

One of these is Rahman, a day labourer.

An ethnic Baloch, he was shot dead in retaliatory killings that took place after the market attack.

"My son was a hard-working young man," said Jaan Bibi, Rahman's ailing, widowed mother.

"He had no political connections; he was the sole breadwinner for our family."

His brother, Imran, says Rahman was stopped with two other men as they were returning from work.

"They let the Urdu-speaking man go, but shot my brother and another man because they were Baloch," said Imran.

Rahman's family lives in Lyari, where the men who attacked the spare-parts market are said to be based.

Security agencies have said that the massacre was the work of the Lyari-based People's Amn (Peace) Committee.

Urban powder keg

But Shakeeb Baloch, a leader of the group, strongly denies this.

"Everybody knows the agencies act on the behalf of the governor here," he said.

Karachi's residents say they no longer trust the government to protect their lives

Dr Ishrat-ul-Ibad, the governor of the southern province of Sindh, where Karachi is located, is an MQM member.

He offered to resign recently, citing loss of control over security agencies.

"We are not a political party; we are just a social group and want to make our voices heard by the government," he said.

"We have never been involved in attacks on anyone, but we reserve the right to defend ourselves."

The Urdu-speaking community is not one to let things lie.

Karachi is the country's business capital and only operational commercial port.

Huge concrete apartment complexes dot the skyline, cheek by jowl with some of the poorest slums in the world.

It is this disparity which underpins almost all the problems in this mega-city of about 18 million people.

People come here from all over the country in the hope of making it big.

But the increasingly limited resources mean greater competition.

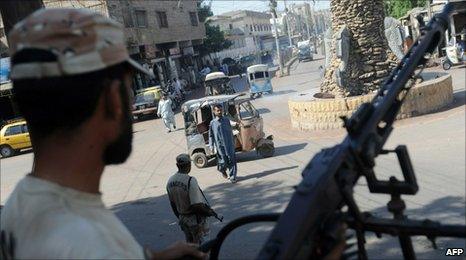

Ethnic groups are increasingly armed with sophisticated weapons; the city is a powder keg.

All of those involved have political connections.

Karachi's residents say they no longer trust the government to protect their lives.

Increasingly, there are calls for the army to take charge.

- Published17 September 2010

- Published20 October 2010

- Published19 October 2010

- Published18 October 2010

- Published17 October 2010