The world of India's anti-graft campaigner Anna Hazare

- Published

Anna Hazare is leading India's anti-corruption movement

Indian activist Anna Hazare says he will begin a new hunger strike on Tuesday in protest against a new anti-corruption law which he and other campaigners say does not go far enough. The BBC's Sanjoy Majumder visited the western Indian village of Ralegan Siddhi to find out more about a movement that is unsettling the government.

Ralegan Siddhi is perched on the hills of the western Indian state of Maharashtra, a small, immaculate village surrounded by lush green vegetation.

In the main village square, groups of elderly men sit around sipping tea and discussing the day's news.

It is an idyllic scene not unlike that found in villages across this country of 1.2 billion people.

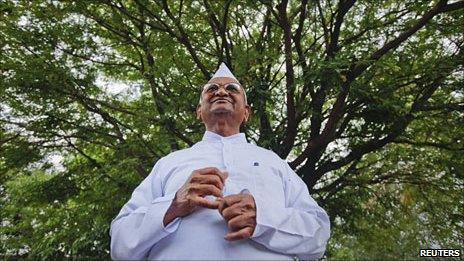

But the tranquillity is shattered by an event that is taking place just a short distance away, next to a Hindu temple and under the shade of an enormous, ancient banyan tree.

A small-built man in his seventies, dressed in white cotton and with a white cap perched on his head, is addressing an impromptu news conference, surrounded by a gaggle of journalists, television cameras and microphones.

Passive resistance

Nearby television satellite trucks beam the conference live around the country.

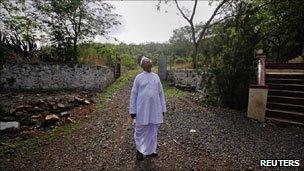

Mr Hazare has launched a number of development projects in Ralegan Siddhi

This is Anna Hazare, the man leading India's anti-corruption campaign and, increasingly, a thorn in the government's side.

His call for passive resistance has struck a chord among millions of Indians, disgusted by unprecedented levels of corruption, and has earned him the sobriquet of a modern day Gandhi.

"It's time to do or die now, just like during our struggle for independence," he tells us wagging his finger.

"Either we succeed in our mission or we make the ultimate sacrifice.

"The government is trying to fool the people of this country - we will not let that happen."

Ralegan Siddhi is where Mr Hazare is from and it is from here that he is directing his campaign, supported by an ever increasing group of volunteers.

It is also where you get a sense of his vision for India.

Model village

Once impoverished, plagued by drought and other problems found in large swathes of rural India, it is now described as a model village by the World Bank after a series of conservation and development projects launched by Anna Hazare over the past decades.

I meet Chaya Manori, a mother of two, as she cooks dinner for her family in her little hut.

"It used to be a terrible place. Crime levels were high, nobody had any jobs and alcoholism was high," she says.

"It's got so much better now."

Thousands turned up to support Mr Hazare's campaign

But while Mr Hazare's efforts may have worked wonders here, bringing about change can be a lot more challenging elsewhere, especially when taking on powerful interests.

Over the past few years, dozens of Indians have been killed or badly injured while trying to expose corruption.

Chandraval is a village more than 200km (125 miles) north of the Indian capital, Delhi.

I visit the family of Jagdish Sharma in their home. A man in civilian dress keeps watch outside, armed with an automatic rifle - inside, the family sit on wooden cots as they speak to me.

Earlier this year they took the village council leader to court, for allegedly siphoning off money from a pension scheme.

Mr Sharma tells me what happened the very same day.

"We were having dinner when a group of men drove up outside the door and started shouting and abusing us.

"We went out to confront them and an argument followed. Hearing the noise, my daughter-in-law rushed out. They drove their vehicle over her and killed her - my leg was crushed under the wheels."

The village head is now in prison facing trial on charges of murder.

Corruption is not unknown to Indians - but many are wondering if it is now beginning to undermine India's emergence as a global power.

Ralegan Siddhi used to be an impoverished village

"It's quite evident that the optimism surrounding India, say a decade ago, has diminished," says Patrick French, a historian who has written extensively on India.

"Many people involved in business, particularly from overseas, complain of having to pay bribes and then don't quite get what they paid for.

"But I do believe that this is the point at which Indians are beginning to sit up and fight back."

It is the reason that the Anna Hazare has received support across the social spectrum and also why it has left the Indian government feeling considerably insecure.

- Published4 August 2011

- Published7 June 2011

- Published13 June 2011

- Published18 April 2012

- Published15 March 2011

- Published3 March 2011

- Published18 January 2011

- Published18 November 2010