Homeless alcoholics drink in comfort at 'wet houses'

- Published

In Minnesota, wet houses allow alcohol addicts the chance to consume alcohol under supervision. One of five facilities statewide is Anishinabe Wakiagun, a Native-American run wet house in Minneapolis.

In Minnesota, some chronic alcoholics are offered a roof over their heads without being ordered to stop their drinking.

Critics call Anishinabe Wakiagun a place of death, but to its 45 residents, one of whom has been here 11 years, it is more like a lifeline.

One resident of the People's House wheels a bicycle down an upstairs corridor, cursing as he goes.

A few doors along, drinking buddies get rowdy over a bottle of cherry vodka. And downstairs, a sign on the outside security door warns against bringing firearms inside.

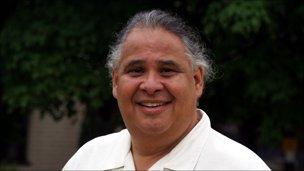

Jesse Beaulieu's mother died of cirrhosis of the liver. Now he struggles with alcoholism

The Minneapolis area's three wet houses vary in approach but all share one common - and controversial - feature: within these walls, no-one stops you drinking.

There are rules. Drinking has to be in the privacy of your room. Don't abuse the staff. And mouthwash, which contains high concentrations of alcohol and is a cheap favourite among chronic alcoholics, is banned.

But if you want to drink yourself into a stupor, or even to death, then go ahead.

While some have, most do not, says Michael Goze, chief executive officer of American Indian Community Development Corp, external, which runs the centre.

Saving money

According to People's House research, its residents indulge in fewer, shorter binges between stays than alcoholics who have not spent time at the centre. (The average stay is 21 months, the centre says).

Residents can drink together, but only in a resident's room

The centre says it saves the county more than $500,000 (£312,441) per year by reducing detox admissions, emergency room visits and jail bookings.

But Mr Goze says the centre reinforces a more fundamental point: you don't have to be sober to have a home.

"There's a lot of subsidised housing throughout the city," he says.

"Are there rules about whether people drink or don't drink? There are not."

At Wakiagun (the name is Ojibwe), residents are well fed and have access to on-site medical advice.

'I crave it'

Jesse Beaulieu, 28, says it represents the difference between life and death.

Herb Sam drinks cheap cherry vodka

"If I wasn't here right now," he says, "I wouldn't be alive."

Death and alcohol have shaped Mr Beaulieu's life since he was a child.

His mother died of cirrhosis of the liver in 2004. His aunt, also an alcoholic, died of exposure on waste ground behind a drug store. His brother found her body and committed suicide. Mr Beaulieu threw himself off a bridge in an attempt to follow suit.

He says he is trying hard to shake the habit, but it's hard. Temptation literally comes knocking on the door most evenings, in the shape of fellow residents looking for someone to drink with.

"Sometimes," he admits, "I just crave it."

But there lies the challenge of the wet house. Unlike other, more prescriptive treatments, it gives you choices.

Options

For Joe Mihalik, an alcoholic since age 18, that is what matters.

Joe Mihalik says after six years in wet houses, he may almost be ready to resume life outside

"When someone tells me I can't do something, I'm going to do everything in my power to do that," Mr Mihalik, now 54, says.

"That's kind of vanquished here. They're saying 'go ahead and drink', and all of a sudden the options fall in my lap."

The People's House doesn't provide alcohol - residents must buy their own.

It is not hard to find them on the nearby streets, scraping together a few dollars by holding up "homeless" or "hungry" signs at traffic intersections, or collecting cans for recycling.

'Cures, not indulgence'

A couple of residents, most of whom are Native Americans, make decorative dream catchers and sell them on the street or at craft fairs.

County Commissioner Jeff Johnson says tax dollars should go to cures, not indulgence

Wet houses are not without their critics. Hennepin County Commissioner Jeff Johnson finds the whole concept deeply flawed.

"We really do enable behaviour that is destroying these people's lives," he says. "And we have the taxpayers' help with that. And I just think that's wrong."

In difficult economic times, Mr Johnson says, tax dollars should go towards cures, not indulgence.

Mr Mihalik disagrees.

"I've been in and out of 12 treatments," he says.

"I can sit at the head of the class. I can graduate with flying colours. But I'm drinking two weeks after I graduate. Alcoholism is terminal. It's not curable."

One last drink

Mr Mihalik has been in wet houses for the past six years and thinks he may just be ready to move on. He looks healthier and more determined than most residents of the People's House.

Chief executive officer Michael Goze says sobriety should not be a condition for housing

Jesse Beaulieu is still some way behind. But as he sits in the safety of his own room, drawing and writing poetry, and occasionally falling off the wagon, he's working on his demons.

"My life is now on the brink," he writes in a poem entitled One Last Drink.

"Do I let my boat float or sink?

"I don't care what anyone thinks.

"I got to answer the question: do I take one last drink?"