Obama's rhetorical balancing act

- Published

- comments

President Obama had publicly opposed a war in Iraq before it began

Mark Anthony said: "I come to bury Caesar, not to praise him."

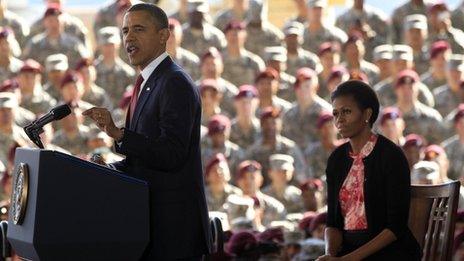

US President Barack Obama's speech at Fort Bragg, North Carolina, was trickier. He had to praise the troops but bury a war he had once called "dumb".

Americans hold their military in very high regard, even as they are much more doubtful and divided about the 10 years of foreign wars.

Many feel lessons had to be learnt from Vietnam, where some think the veterans were treated with contempt because they had the bad luck to fight in a war judged a mistake and a failure.

So Mr Obama could not simply announce the war over without going out of his way to thank those who fought.

He said they had "shown why the United States military is the finest fighting force in history".

Papering the cracks

The superlatives fell thick and fast.

Of course, logically, you can show courage and resolution in a foolish cause. But no-one wants to be told their sacrifice was for nothing. So Mr Obama listed the merits of a war he has always opposed.

He said "everything that American troops have done in Iraq - all the fighting and dying, bleeding and building, training and partnering, has led us to this moment of success.

"Of course, Iraq is not a perfect place. But we are leaving behind a sovereign, stable, and self-reliant Iraq, with a representative government that was elected.

"Iraqis have a chance to forge their own destiny."

Indeed, he seemed more explicit in his praise for the principles behind the war, not just its outcome.

He told them: "Never forget that you are part of an unbroken line of heroes spanning two centuries.

"From the colonists who overthrew an empire to your grandparents and parents who faced down fascism and communism, to you: men and women who fought for the same principles in Fallujah and Kandahar and delivered justice to those who attacked us on 9/11."

This is more than a little awkward, intellectually.

Mr Obama comes close to agreeing with those who backed the invasion in the first place. That for all the fantasy about weapons of mass destruction, all the mistakes and lack of preparation, the world is a better place for the war.

But it is not politically awkward. Few will notice; few are talking about it.

It looks more like fair-minded generosity than hypocrisy.

But he is papering over the cracks between what he has always thought and what he has to say to the country.

Mark Anthony goes on: "The evil that men do lives after them; the good is oft interred with their bones."

Maybe it is different for wars.

It is an irony that Mr Obama, in one sense elected for his opposition to the Iraq war, has drawn a line under the conflict stressing its virtues, not its vices.

- Published14 December 2011

- Published14 December 2011