Trayvon Martin's death puts Sanford, Florida on edge

- Published

In Sanford, Florida, the shooting death of an unarmed teenager has tapped into decades of resentment and put the town on edge.

Seventeen-year-old Trayvon Martin was killed by a self-appointed town watch patrolman more than three and-a-half weeks ago. But for residents of Sanford, Florida, the crime still feels fresh.

When Martin was killed on 26 February, police declined to charge the shooter, George Zimmerman, who claimed he fired in self-defence and in accordance withFlorida's "Stand Your Ground" law.

But in the past week, that decision has attracted the attention of both the global media and outraged activists, who claim Mr Zimmerman got away with murder.

Since the story of Mr Martin's death appeared in the New York Times on Saturday, over a million people have signed an online petition seeking George Zimmerman's arrest.

Protests have taken place in New York and Miami, and Sanford has been inundated with attention and visitors, including a planned rally on Thursday led by the civil rights activist Rev Al Sharpton.

'Age-old pattern'

When Rev Sharpton gets here, he'll find a town brooding with resentment over what most African-Americans regard as the local police department's inexplicable failure to arrest Mr Zimmerman.

The city's belated efforts to explain why Florida law might actually prevent such an arrest probably come too late to change this.

In part, this is because too many local people regard the death of Trayvon Martin as part of an age-old pattern of abuse and discrimination.

At a Methodist church in a poor black neighbourhood on Wednesday, ceiling fans stirred the warm, muggy air as one resident after another took the microphone to tell tales of police beatings, deaths in custody and official lies.

Martin was walking home after purchasing sweets and a tea when he was shot by Zimmerman

The stories, solicited by Benjamin Jealous, president of the African-American rights group the NAACP, came thick and fast and were impossible to verify. Some rang true, others seemed incoherent.

It felt like an event from another era.

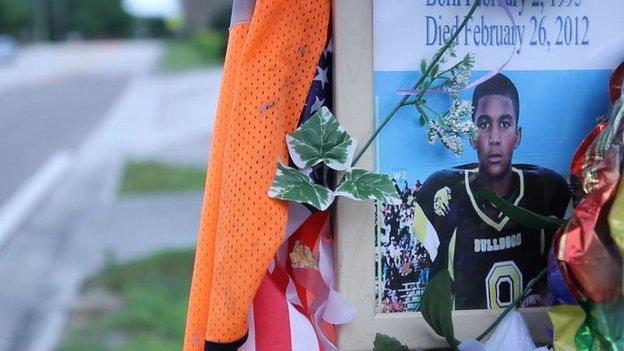

Across town, near one of the entrances to the gated community where Mr Martin was shot, a makeshift memorial threatens to smother a road sign.

There are flowers, balloons, teddy bears growing soggy in the rain and, inevitably, a can of iced tea and some Skittles - the items Mr Martin was carrying when he was shot by George Zimmerman, who had earlier called 911 to report the youth as suspicious.

Nearby, a neighbourhood watch sign reads "Program in Force: We Report All Suspicious Persons and Activities to the Sanford Police Department."

Stocking up

Is there tension in Sanford? Yes. As I open the gate into The Retreat At Twin Lakes, hoping to find someone to talk, a woman in a black SUV angrily threatens to report me for trespassing.

Another couple, out for an evening walk, tell me that everyone is on edge and they worry about what might happen.

And in a gun shop back in the run-down part of town, the staff - who won't be interviewed on the record or identified - say that on Tuesday they refused to sell weapons to two black men who seemed to be spoiling for a fight.

Customers are stocking up on ammunition, the staff say. Self-protection seems to be on people's minds: from the vague threat of danger but also, probably, because they fear, rightly or wrongly, that somehow this tragedy will cause the government to think again about gun control.

For all the anger and the frustration evident here, Sanford doesn't feel like a powder keg, waiting to explode.

There is resignation here, too. People sense that with the justice department involved and a Florida grand jury set for next month, the wheels of justice are turning, however slowly.

Rev Al Sharpton still thinks he needs to be here, despite the death of his mother. As he addresses a community in crisis, how carefully will he choose his words?

- Published22 March 2012

- Published20 March 2012

- Published20 March 2012

- Published20 March 2012

- Published20 March 2012