Can Washington learn from Californian budget compromise?

- Published

California has imposed tax rises and spending cuts to turn round its budget deficit

Four years ago, the state of California was on the brink of bankruptcy.

It had been hit hard by the financial crisis. Unemployment was higher than the national average, as was the rate of mortgage repossessions.

Tax revenues were in steady decline, while expenditure had ballooned.

California's budget deficit stood at $11.2bn (£7bn) and in the state legislature Republicans and Democrats were at loggerheads over whether to cut services or raise taxes.

A budget was finally signed off by Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger three months late.

That included tough measures. State employees were asked to stay at home without pay for two days each month to reduce expenditure.

State offices were closed on the first and third Friday of each month.

But the situation did not improve. By the middle of 2009, the state government began issuing IOUs to meet its short term financial obligations. The rating agencies downgraded its bond-rating.

Arnold Schwarzenegger was forced to pass emergency legislation in 2008 and 2009

Yet four years on, California is projecting a budget surplus of more than $1bn for the 2014-2015 fiscal year.

Employment is rising faster than the national average and a report by the state's Legislative Analyst's Office, external said California had reached "a promising moment: the possible end of a decade of acute state budget challenges".

Balanced budget

How did the state manage such a turnaround in its fortunes?

Firstly there have been swingeing cuts in state expenditure. Education has been hardest hit, with many lay-offs and a 30% rise in university fees.

State salaries have been cut and there have also been reductions in spending on healthcare and prisons.

Secondly, the political deadlock has been broken - Democrats now have a "supermajority" in the state, controlling the governorship and both houses of the state legislature.

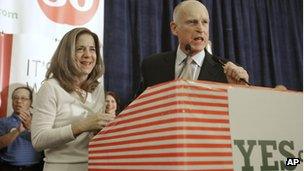

Even so Governor Jerry Brown went directly to the electorate with a plan to achieve a balanced budget, something he has called a moral imperative.

Proposition 30 has been called the "Millionaires Tax" - except that in its final form it will affect everyone who earns more than $250,000 a year.

Four new tax brackets have been created for incomes above that threshold. Those who earn more than $1m will have to pay significantly more tax, backdated to the beginning of 2012.

Governor Brown's proposition was overwhelmingly approved on election night in November and combined with an increase in state sales tax, this is hoped to generate an extra $6bn in revenue.

Democratic California State Assembly member Bob Blumenfield, who chairs the Assembly Budget Committee told the BBC: "California clawed its way free from budget deficits through balancing tough cuts with new revenues and reforms that capture greater efficiency in government."

"After years of financial instability, we now have our best budget forecast in over 10 years. Every Californian can take great pride in this."

Overtaxing

But there are critics. Californian Republican Representative Darrell Issa, is one and told the Financial Times newspaper: "Dramatically increasing taxes on entrepreneurs and small business owners, as Prop 30 does, is going to hasten the exodus of employers from California to other states, and the jobs and tax revenue will go with them."

Others say the new tax thresholds will increase budget uncertainty in the state.

Governor Jerry Brown worked hard to secure passage of his programme of tax rises, Proposition 30

Ross De Vol of the non-partisan Milken Institute in Santa Monica, California believes the tax rises make the state too reliant on the highest earners and the national economy.

"After Prop 30, the top one percent of income earners end up paying, by my calculations, north of 50 percent of personal tax revenues," he says.

"The folks in (the state capital) Sacramento have made themselves more susceptible to fluctuations in the markets. Governor Brown has, in effect, bet it all on black."

Mr Blumenfield agrees that much now depends on what happens in the capital: "My concern is that our hard-gotten gains can be undone if partisan gridlock prevails in Washington and our nation goes off the fiscal cliff."

Republicans and Democrats in Congress are unable to agree whether the budget deficit is best tackled by cutting expenditure or raising revenue.

Changing landscape

In the recent past, only expenditure was up for negotiation, but as Mr Blumenfield points out, in California both sides of the equation were addressed and Ross De Vol says there is a new willingness to examine revenue.

"There's a changing political landscape, which Republicans are beginning to recognise," he told the BBC.

Mr Obama scored a decisive re-election victory in part campaigning for raising taxes on higher incomes.

Since the November election, the president's approval ratings have risen, and opinion polls have shown a strong majority not only favouring his tax position, but saying they will blame Republicans for a failure to reach a deficit deal.

Mr Obama had originally called for rises, as in California, for those earning more than $250,000. In negotiations with House Speaker John Boehner, that threshold had risen to $1m.

"People are happy to see taxes go up for millionaires," Mr De Vol says. "And the Republican leadership are willing to allow higher tax rates - let's not call it a tax increase."

But Mr De Vol warns that over-reliance on revenues cannot work in the long term. "If you carry on milking the cow, eventually the yield's going to go down. There has to be a trade-off."

That a minority of Republicans continue to block any compromise and oppose tax rises of any kind may yet lead to the US walking off the fiscal cliff.

That would bring about deep cuts in expenditure and sharp tax rises to slash the budget deficit, a correction that analysts say could cause a new recession.

But some economists, including former White House economic adviser Jared Bernstein, argue that if temporary measures are put in place to avoid an economic downturn, there is a greater chance to work out a long-term solution that necessarily will follow some of the methods chosen by California.

- Published15 May 2012

- Published27 June 2012