Calling time on America's blockade of Cuba

- Published

The Castro government has long blamed the embargo for its shortcomings, arguing that it has served to keep ordinary Cubans cut off from the world

On 19 October 1960, less than two years after Fidel Castro swept into Havana, the United States announced its economic embargo of Cuba. It has been in place ever since but now it is under scrutiny again.

In a recent editorial, the New York Times called for the embargo to be lifted.

The newspaper outlined a host of ways in which it says the measure had been counter-productive to US interests and those of the long-suffering Cuban people.

"Over the decades, it became clear to many American policy makers that the embargo was an utter failure," the editorial said.

Could they soon see a world where relations with the US become more cordial?

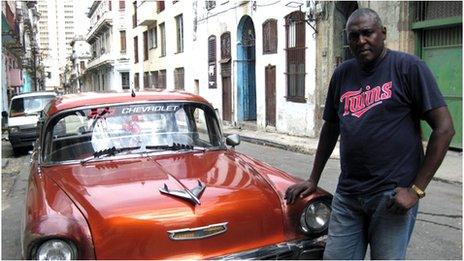

Old-fashioned vehicles plying the streets of Havana are one interesting off-shoot of the embargo

It is argued that sanctions have been harmful to the long-suffering Cuban people as well as being counter-productive to US interests

Among the legislation through which the measure is enforced is the Trading with the Enemy Act of 1917 as well as the inclusion of Cuba on a US state department list of state sponsors of terrorism, alongside Syria, Iran and Sudan.

Although the embargo cannot be ended without the backing of Congress, the newspaper argued there was much President Barack Obama could do unilaterally - from removing Cuba from the list of state sponsors of terrorism to lifting caps on remittances.

"Mr Obama should seize this opportunity to end a long era of enmity and help a population that has suffered enormously since Washington ended diplomatic relations in 1961," it said.

It certainly caught the attention of Fidel Castro who wrote an article of his own in the state newspaper, Granma, extensively quoting the New York Times editorial, external.

'Cold War product'

Michael Shifter, director of the Inter-American Dialogue think-tank in Washington DC, believes the New York Times editorial was a "sound appraisal" and "cogent case".

"The embargo was a product of the Cold War and a very intense moment in the Cold War," he says.

"I'm not sure it even made sense then, but certainly it just doesn't make sense today. It is anachronistic.

The Cuban government says that the costs of the embargo to the economy have been astronomical - about $117bn

Cuba may have the raw materials, but the embargo has made it harder for them to be exported

"Its double standards and hypocrisy are so glaring - the United States has closer diplomatic ties and trade relations with many governments that are far more authoritarian than Cuba's."

But he still does not expect the embargo to be lifted any time soon: "There are some strong, powerful Cubans in Congress that can make life difficult for the administration at a time when it needs as much support as it can get.

"I think this is not something that really occupies a lot of time at the highest levels - especially given what else is going on in the world."

'Injustice'

Most ordinary Cubans are simply exhausted by the impasse.

"It's unjust," says electrician Juan Carlos, as he waits in a long queue outside a government bank in central Havana.

"They have condemned a whole population no matter what our political views might be. We don't deserve this. It's obsolete."

Some argue that the embargo is a relic of the Cold War and should not still be applied in the 21st Century

The government has taken tentative steps to liberalise and diversify Cuba's tightly controlled economy

His view is echoed by the next person in the queue. "Enough already!" says retiree Orlando Garcia. "So many years of this. Everything in life should have a start point and an end - I hope we're nearing the end of this."

Of course, the New York Times's call for change also came in for heavy criticism, particularly from Cuban-Americans online and on Twitter.

Much of the criticism focused on the fact that it had said in one breath that the embargo had "forced Cuba to make reforms", while also describing the embargo as an "utter failure".

It cannot be both things at once, its supporters say.

Yet many argue that the relatively recent economic reforms do not justify the past five and a half decades of restrictions on Cuba.

'A gift'

The Cuban government delivered its latest report on the effects of the embargo, or "the blockade" as they call it, inside a school for children with learning difficulties.

Their inference was clear: these are the kinds of places that suffer because of Washington's policy towards Cuba.

But Shifter believes its effects can be seen another way. The embargo has presented the Castro government with "its rationale for the way it conducts itself".

"The embargo has given Fidel and the regime a gift," he says.

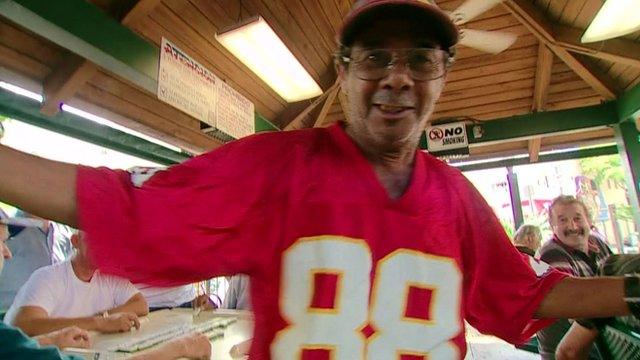

The embargo is supported by many Cubans in the US

Either way, the economic impact has undoubtedly been huge. The Cuban government says that the costs of the embargo to the economy have been astronomical, about $117bn (£72.6bn).

It is not just in the economic sphere that the embargo is felt either.

"A distant relationship with the United States is always difficult for any country but is particularly tough for a country like Cuba," acclaimed Cuban writer Leonardo Padura told the BBC in Havana recently.

"For example, during the Bush administration, cultural exchange programmes practically disappeared."

Over the years, the United Nations' General Assembly has voted 22 times on the embargo, and every time member states have voted overwhelmingly in favour of lifting it.

In general, only the US and Israel oppose the proposal.

Later this month, the UN will hold vote Number 23. There is little to suggest it will be any different.

It will then be down to the Obama administration to decide whether to consign the longest trade embargo in modern times to history.

- Published19 May 2014

- Published20 May 2014

- Published11 October 2012

- Published7 February 2012