Will Iran and the US shake hands in 2017?

- Published

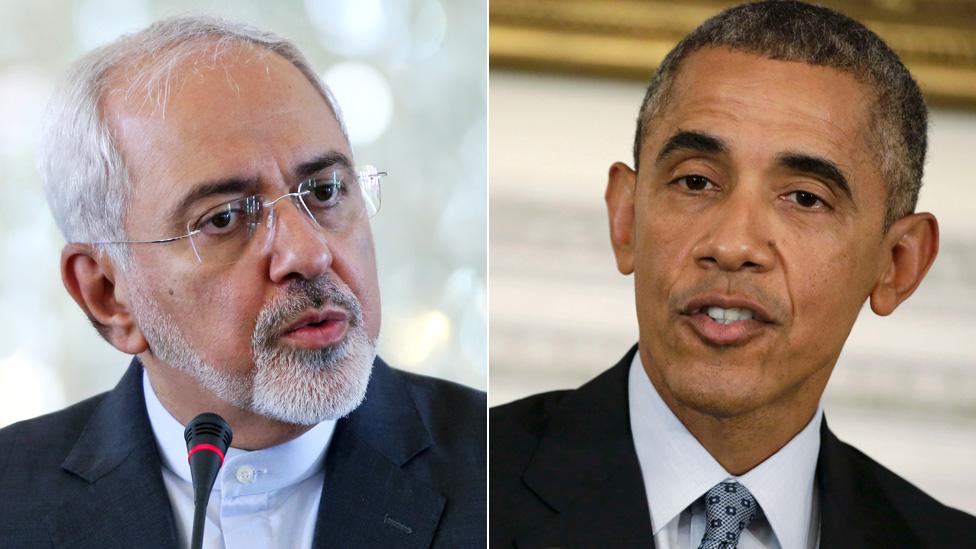

Javad Zarif has been criticised for shaking hands with President Obama

When he addressed, external the UN General Assembly last week, Iran's president Hassan Rouhani struck a mostly positive note, proclaiming a new era of engagement with the outside world.

But there was no handshake with President Obama, not even a phone call like the one in 2013.

Perhaps Mr Rouhani was eager not to attract the ire of hardliners back home at a delicate moment in Iranian politics, and while a parliamentary review of the nuclear agreement was still under way.

His foreign minister on the other hand, Javad Zarif, did shake hands, external with the US president and was duly denounced as a traitor in Tehran by hardliners.

He will be hauled in front of parliament to answer questions about crossing a red line with the enemy.

It is certainly not enough to sign a nuclear agreement to end four decades of enmity, but the political process in both countries is now also a key element in how the ties evolve.

Both countries are entering an election cycle that will set the tone of the unfolding relationship after 2017.

Iranians want to know who Mr Obama's successor will be in the White House.

The Americans are wondering how long they will be dealing with a centrist like Mr Rouhani.

Iran will hold parliamentary elections in February and reformers are hoping they can regain the majority they lost in 2004.

It is a tall order - but in a BBC interview in August, one of Iran's Vice Presidents, Massoumeh Ebtekar made clear that Mr Rouhani believed that the nuclear agreement gave him leverage over the other political parties.

Economic change key

The reformers' success depends on the president's ability to deliver tangible economic change to the country, including those possible thanks to the expected lifting of sanctions following the implementation of the nuclear deal.

This will, in turn, determine whether Mr Rouhani has any chance of being re-elected in 2017.

The US and Iran have been mirroring each other in their political handling of the nuclear deal.

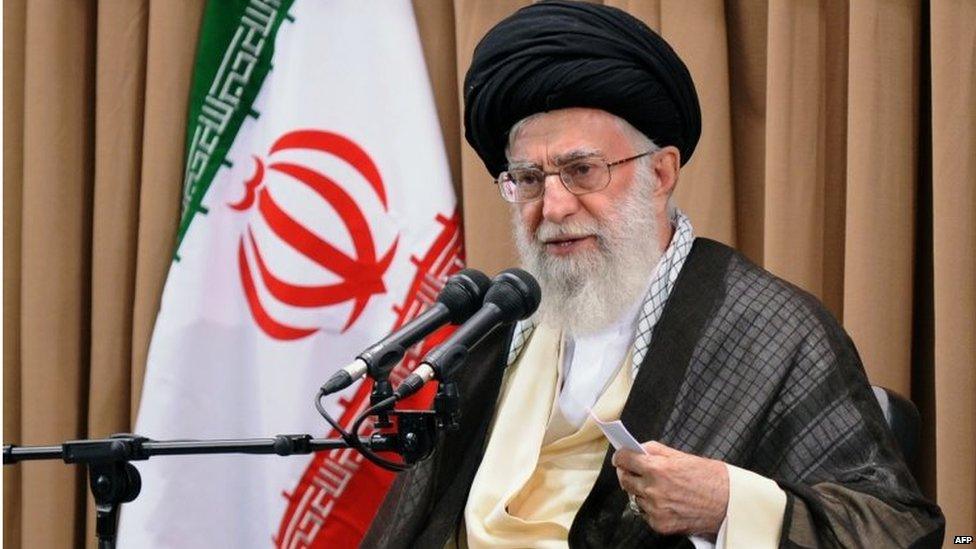

Ayatollah Khamenei will have the final say over whether to accept or reject a nuclear deal

Republicans in Congress tried to sink the agreement by voting on a motion of disapproval in September.

But the Democrats gathered enough votes to block the motion and handed Obama a political victory.

In Iran, the Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei ordered a vote in parliament on the nuclear deal and a special parliamentary committee took its time before finally issuing its recommendations, external on Sunday.

It was always unlikely that the Iranian parliament would reject the deal outright, but the process helped hardliners keep their options open while they waited for the outcome of the tussle in Congress.

The continuing debate is also a way to keep Mr Rouhani's toes to the fire.

The committee approved the deal with caveats - no foreign inspections of military sites and no curbs on the missile programme.

This will again allow Iran to remain nimble as it watches the presidential race unfold in the US.

Republican opposition

In the US, several Republican candidates have promised to abandon the controversial agreement on day one of their presidency, even though it was a multilateral accord.

Ted Cruz has even made an oblique threat to kill , externalthe Supreme Leader.

Jeb Bush has been more pragmatic, saying that tearing up the agreement was not a policy, though he didn't exactly endorse the deal either.

Hillary Clinton, who was secretary of state when the back channel with Iran was established, gave a robust endorsement of the agreement during a speech in September.

Hillary Clinton has backed the deal

But she made clear the success of the deal depended on verifying Iran's implementation of it and she emphasised that Tehran should be confronted about its aggressive behaviour in the region.

Iran's hawkish foreign policy will not soften while Tehran feels it has the upper hand in the region.

But while the core national security interests of countries don't change based on who is president, personal relations between leaders can set a different tone.

The contrast is stark, for example, between the relationship President Obama had with his Russian counterpart when it was Dimitri Medvedev and the glacial one now with Vladimir Putin.

So what combination of American and Iranian presidents will the elections in Iran and the US deliver as the election cycle takes off in both countries?

A match of hard-hitting rhetoric with Marco Rubio and a hardliner in the vein of Mahmoud Ahmadinejad?

A mismatch of a moderate and a hardliner could also be a missed opportunity for the two countries, for example with a Ted Cruz and a Hassan Rouhani.

Ted Cruz has taken a hard line against the deal

In both those cases, the nuclear deal could still survive if it is being properly implemented, though the relationship would stagnate.

Mehdi Khalaji, an Iran analyst at the Washington Institute for Near East Policy, cautions that the Supreme Leader still runs the show and controls the state apparatus so he will set clear limits on how much further president Rouhani can go in a rapprochement with the US if he is re-elected.

But if the US and Iran, once allies, but separated by a revolution and a hostage crisis 36 years ago are to make more steps towards an entente, a handshake between a reformer like Mr Rouhani and a Democrat like Mrs Clinton at the UN General Assembly 2017 could set the tone.

Or at least an in-person meeting since Mr Rouhani, a cleric, wouldn't be able to shake hands with a female president.

Key areas of the nuclear deal:

Uranium enrichment: Iran can operate 5,060 first generation centrifuges, configured to enrich uranium to 3.67%, a level well below that needed to make an atomic weapon. It can also operate up to 1,000 centrifuges at its mountain facility at Fordow - but these cannot be used to enrich uranium.

Plutonium production: Iran has agreed to reconfigure its heavy water reactor at Arak, so that it will only produce a tiny amount of plutonium as a by-product of power generation, and will not build any move heavy water reactors for 15 years.

Inspections: International monitors will be able to carry out a comprehensive programme of inspection of Iran's nuclear facilities.

Possible military dimensions: Iran will allow foreign inspectors to investigate the so-called "possible military dimensions" to its programme by December. This should determine whether the country ever harboured military ambitions for its nuclear programme - a claim it has always strenuously denied.

Sanctions: All EU and US energy, economic and financial sanctions, and most UN sanctions, will be lifted on the day Iran shows it has complied with the main parts of the deal.

- Published8 September 2015

- Published2 September 2015

- Published23 November 2021