Should we give every homeless person a home?

- Published

The Canadian city of Medicine Hat recently became the first city to end homelessness thanks to a surprisingly simple idea: giving every person living on the streets a home with no strings attached.

Unlike many other homelessness initiatives, the so-called "Housing First" approach doesn't require homeless people to make steps towards solving other issues like alcoholism, mental health problems or drug addiction before they get accommodation.

Four experts talk to the BBC World Service Inquiry programme about how and why the approach works and some of its limitations.

Sam Tsemberis: The light bulb moment

Dr Sam Tsemberis is a clinical psychologist who founded Pathways to Housing in New York City in 1992, and developed the Housing First model.

"In the 1980s I was working at Bellevue Psychiatric Hospital on the east side of Manhattan, and I walked about 30 blocks to work.

"I began to walk past people that I recognised, people I had treated when I was working on the inpatient service at the hospital. They had gotten discharged, and were on the street, sometimes literally in the pyjamas that they had been discharged with from the hospital. It was quite disturbing.

"Many of them told me over and over again, 'I need a place to stay, a simple, decent, affordable place of my own like I had before I became homeless'.

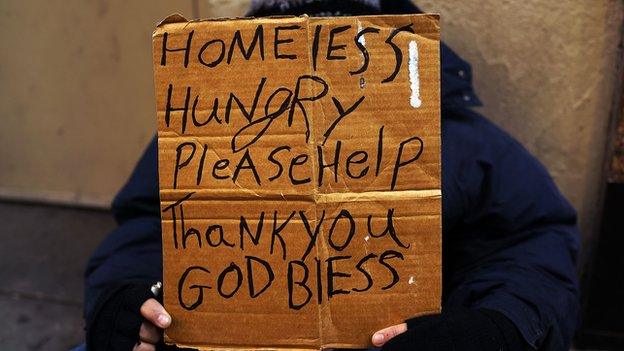

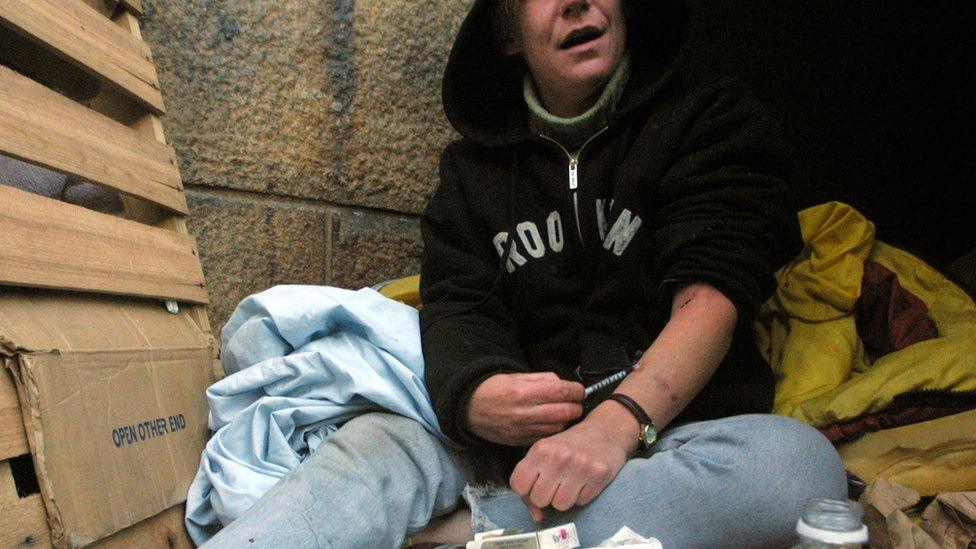

Many homelessness projects demand that people stop taking drugs before receiving help

"People had to participate in psychiatric treatment or be clean and sober in order to get housing. That was a precondition. And curing addiction or curing mental illness is still something we don't know how to do, and that was exactly what was being asked of people. It was an impossible hurdle to jump over.

"We began to do something that no-one had really done before, which was to take people on the street and offer them a place to live, no conditions other than sign the lease and pay your rent.

"The other breakthrough was to offer normal housing. We rented housing from community landlords on the open market, and people lived in apartments with families, older people, younger people, students, people of all types, including some people who had just the day before been homeless, but were homeless no longer.

"In that first year we had 50 people. The rule-of-thumb in most treatment programmes is a third do better, a third do worse and a third stay the same.

"At the end of the first year 84% were still housed: 84% of people who had been on the street for years. We knew we were onto something very important.

"At first it was misunderstood, and I think people were very uncomfortable because they thought of it as enabling something that should be earned, but if you back up from moral judgments, homeless people are already suffering and providing them with a house actually gets us much closer to the goal that we all want.

"We all want people off the streets and living a productive, meaningful life. This is just a much quicker, more effective and cost-saving way of getting to exactly that goal."

Philip Mangano: The conversion

Former music executive Philip Mangano was inspired to start helping homeless people after watching a film about St Francis of Assisi. He left his job to volunteer at his local church. Twenty years later he was appointed President George W Bush's homelessness czar, where he came across Sam Tsemberis' work.

"We had some very good research that indicated that a certain portion [20%] of homeless people were experiencing what was termed 'chronic' homelessness; they were homeless for a year or more and had a disability or concurring disabilities. So as a policy decision in Washington, we decided that we would focus specifically on that population of homeless people.

"I heard about a guy in New York who was placing people directly into housing off the streets and frankly, I was completely agnostic that that could be done, but I thought if that works, we better know about it.

"He took me to a number of people that had been housed, and it looked as though Sam had uncovered something that was in a blind spot for the entire issue for a quarter of a century. So I was interested in the tangible aspects of it, but I really wanted to look at the data. Was there confirming data and research that indicated that this approach worked? Yes there was. So I was a convert to Housing First.

"One of the key questions became how can we possibly afford housing for all these people?

"How much did homeless people cost when they were randomly ricocheting through very expensive health and law enforcement systems, the emergency room of the hospital, police interventions, court costs, and incarceration costs? How much did that cost, versus how much did it cost for people when they were placed in housing?

"Every single study we did revealed that it was less costly to provide the housing and the services than it was to have those people randomly ricocheting in expensive health and law enforcement systems.

"So you could spend up to $150,000 (£103,000) enabling a person to be homeless because you're not providing them with the solution. Or you could invest up to $25,000 (£17,000) and people would be in housing, stable, secure and safe [with] hardly any police interventions or utilisation of emergency rooms. You didn't need to be Warren Buffet to figure out which of those was the better investment.

"More than 1,000 communities got involved from around the United States, and we set the goal that we could end chronic homelessness - the homelessness of the most vulnerable, the most disabled, the most likely to die on the street. We could end that form of homelessness in our country in 10 years.

"We saw in the first five years about a 40% decrease in chronic homelessness around the country. Some cities achieved 67-70% decreases.

"But at this point, right now, I can think of only a couple of cities in the country that have actually ended chronic homelessness. The recession hit; administrations changed. Some of the attention got dissipated. That led to resources being dissipated. You didn't have that same concentration and so you didn't have the same outcomes and results.

Dr Josh Bamberger: Trouble in the Tenderloin

Dr Josh Bamberger is the former medical director of housing, San Francisco, and implemented Housing First in the city, providing homes to more than 10,000 homeless people, mainly in an area called the Tenderloin.

"Like every other city in the United States, we had a ten-year plan to end homelessness and, as I'm sure you're aware, homelessness still exists in San Francisco.

"It's disappointing that it doesn't really feel like there's been much shift in the number of people who are lying on the streets in the Tenderloin, which is the inner-city portion of San Francisco, in 15 years.

"The Tenderloin is a densely-populated area. They're small apartments, 300 square feet, sometimes the bathrooms are down the hall. There are probably 1,000 or 1,500 of these buildings with 150 small apartments in them. It's loud, there's a lot of activity going on and there's a lot of drug dealing that goes on in the streets,

"I think if you're struggling with sobriety and people are offering you drugs and alcohol on a regular basis, it's harder to make progress.

"In San Francisco, we are in this very challenging conundrum where the cost to rent an apartment is beyond the means of low-income people. The average cost of a studio apartment in San Francisco is something like $2,500 a month (£1,700) and if you're getting benefits from the government, the most you can make is about $950 (£650) a month, so that's a huge gap that is never going to be overcome.

"We housed the wrong people. When you have such great demand for limited resources, then you need to be very exact and very courageous in only offering housing to the people who need it the most. We used our very limited local resources for people who are just low-income. We didn't focus on the highest users of the healthcare system first.

"What we should have done from the beginning is only offered housing to the 20% of people who are chronically homeless, and then used that opportunity to disclose that the government isn't investing in expanding the affordable housing sector adequately."

Jamie Rogers: Miracle in Medicine Hat

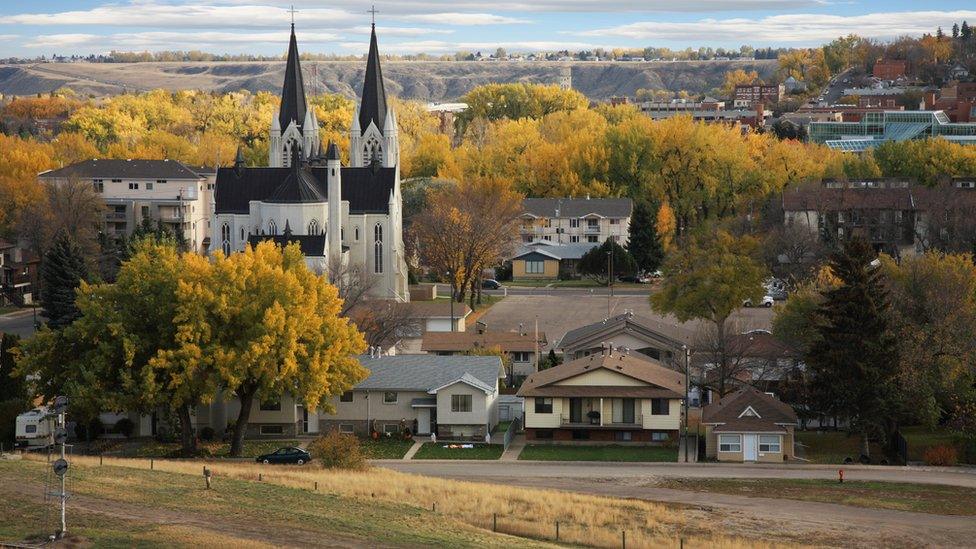

Jamie Rogers ran the Housing First programme in the Canadian city of Medicine Hat, which has eradicated all homelessness, defined as meaning no-one will have to sleep rough for more than 10 days before they have access to stable housing.

"Medicine Hat is in South Eastern Alberta, a community of about 63,000 people. It's a very family-focused community.

"I first heard about Housing First from a trip that I took to Toronto. I have to be really honest: I was probably one of the biggest sceptics that it would actually work.

"Since April 2009, this community has collectively housed 1,013 individuals; 705 adults and 308 children.

Medicine Hat's experience of Housing First is being closely followed by other cities across the world

"We take an extremely targeted approach to look at those that are in greatest need or closest to death, which typically are those who are chronically homeless, and are living in places that are unfit for human habitation.

"We did not have to build housing per se. We have a very limited number of units strictly for housing the homeless. What we do very well is build relationships with landlords and property management and communities, and use market housing.

"[Initially] landlords were extremely sceptical. They were worried about bed bugs, increased violence and drug dealing, so we worked really hard to present factual information about who we actually serve. And we've seen progress. We have 175 different landlord and property management companies on board with us and we now have landlords calling us.

"If you ended up on the streets of Medicine Hat tonight, you could spend one night in the shelter and be speaking to a worker within three days. And you could be on a wait list for a house as quick as tomorrow.

"Rather than just introducing programmes like Housing First, we have restructured our entire system approach to ending homelessness.

"We take the stance that people are worthy of a home and it is a fundamental human right to have shelter and a roof over one's head. Of course it is recovery-oriented, and we help and support people in making different choices in their life, but we don't withhold housing because of who they choose to be.

"Housing First works. I cannot say it enough: it absolutely works."

The Inquiry is broadcast on the BBC World Service on Tuesdays from 12:05 GMT. Listen online or download the podcast.

- Published14 April 2016

- Published10 February 2016

- Published8 March 2015

- Published16 October 2013