CIA taps huge potential of digital technology

- Published

Technology is revolutionising the work of the CIA

At CIA headquarters in Langley, the office of the director of digital innovation sits next to the agency's in-house museum filled with artefacts from its history.

Featuring heavily are gadgets such as early secret cameras and bugging devices that would not appear out of character in a Hollywood film.

The line-up makes the point that even though the CIA is an intelligence agency whose central mission has been to recruit people to provide secrets, technology has always had a crucial role.

Andrew Hallman - who runs the recently created Directorate of Digital Innovation - has the job of making sure that the new digital world works to the CIA's advantage rather than disadvantage.

A major focus of Mr Hallman's effort is to use data to provide insights into future crises - developing what has been called "anticipatory intelligence".

This means looking for ways in which technology can provide early warning of, say, unrest in a country.

"I think that's a big growth area for the intelligence community and one the Directorate of Digital Innovation is trying to promote," Mr Hallman says.

The volume and variety of data produced around the world has grown exponentially in recent years - a process about to accelerate as more and more items as well as people are connected up in the so-called internet of things.

The ambition is to take this wealth of data and combine it with analytical models fine-tuned with insights from social sciences to spot where an issue such as food scarcity might be emerging and might, in turn, lead to instability in a region.

This might also involve looking at social media to perform "sentiment analysis" that can help understand if the mood in a population is turning sour.

The CIA hopes to be able to anticipate major events, such as the so-called Arab spring

The idea would be to spot a major change, such as the so-called Arab spring, as early as possible and provide policymakers with the kind of advanced warning they often crave and which intelligence agencies are sometimes criticised (fairly or unfairly) for failing to deliver.

These are often the kind of events not susceptible to the traditional intelligence gathering spies normally carry out - the emergence of protest groups in the Middle East was not a secret locked in a safe or in the mind of a leader that could be stolen or enticed out.

But the techniques of big data, some believe, may offer answers.

Mr Hallman, crisp in both words and appearance, is careful to explain this will not provide a crystal ball that can predict "point events" - for instance that the breakdown of order will happen on a particular day - but, instead, will point to a social or economic system becoming more fragile than might be superficially apparent.

More broadly, the directorate aims to change the culture as well as the structure of the CIA - bringing in technology and integrating it into every part of the agency's work.

The CIA has 10 mission centres where analysts and operators work together on either parts of the world or issues (with centres for Africa, the Near East, Counterterrorism, and Weapons and Counter-proliferation).

Digital officers will integrate into these and bring with them expertise in cyber-techniques, data sciences and software development.

The aspiration is that where some new technological innovation is pioneered in one mission centre, the Directorate for Digital Innovation will see if it can be pushed out to other centres.

Developing expertise in open-source (publicly available) information is another priority - in the past this was something of a sideshow at an agency that focused on "secrets" - but such information can often help focus on what really is secret and what can be obtained by other means, especially as the definition of open source expands rapidly from the past, when it largely meant foreign news and media.

This might involve understanding how a group such as so-called Islamic State (IS) uses social media and working out what options there are to address it.

Alex Younger says there is an arms race in intelligence technology

Data is also changing the sharp end of human intelligence.

The head of Britain's MI6, Alex Younger, has described a high-stakes arms race in technology.

Spy agencies can use data to improve the way they find the secrets and people they are after.

But foreign security services can also use data to track down intelligence officers and identify them, using the digital exhaust we all leave in our wake in the modern world (one reason for the neuralgic reaction within the US government to the cyber-theft of vetting information from the Office of Personnel Management last year, which could be used to identify spies).

This poses fundamental challenges to the old concepts of operating clandestinely and "undercover".

"It is an existential challenge, which we are looking at very closely," Mr Hallman says.

He stresses though that the issue of how far data enables or restricts spy agencies will ultimately depend on their ability to adapt.

"That's entirely on us and how aggressively we can pursue both avenues," he says.

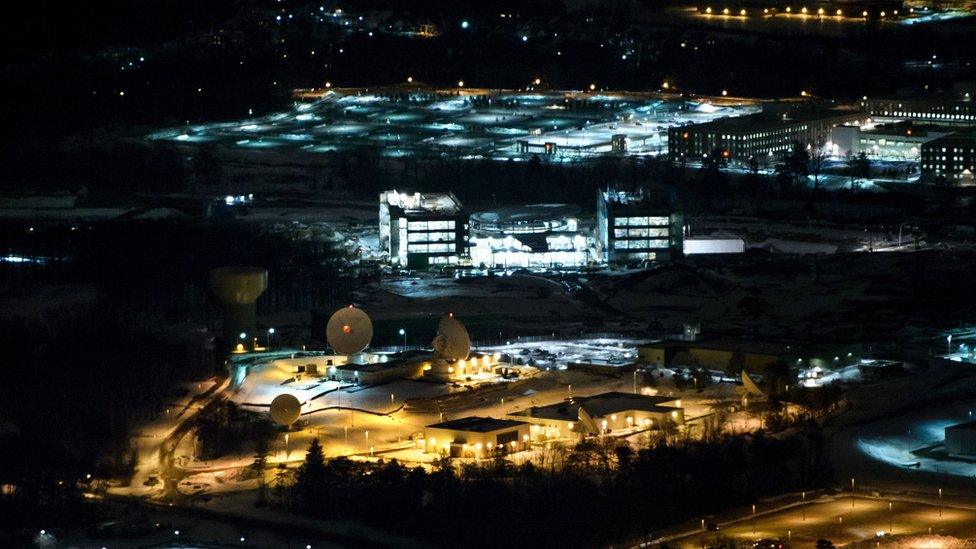

The CIA will be working closely with the National Security Agency

Intelligence officers in the field will need to become much more technologically adept rather than relying on the kind of human wiles and guile so highly prized in the past.

"Operators have to figure a way to enable them both to operate clandestinely and have at their fingerprints with them the digital capability to extend their reach," says Mr Hallman.

Human intelligence and cyber-espionage are increasingly merging.

This means agencies such as the National Security Agency (which focuses on cyber-espionage) and CIA (which focuses on human intelligence) will need to work together much more, something the US intelligence community has sometimes struggled to do.

This new world of digitally enabled espionage will also require a different model of working with the private sector where cutting-edge technology is being developed (the private sector pioneers many of the big data analytics to try to extract value or sell advertising from the information they collect).

Previously, by the time a company brought in a product to meet a need at CIA, it might already be out of date.

"We used to try to make long strides to catch up with the state of the art," Mr Hallman says, "but we need instead to ride a crest of innovation."

The relationship with Silicon Valley, he acknowledges, has been affected by the allegations of former NSA contractor and whistle-blower Edward Snowden.

Edward Snowden:

Ed Snowden explains why he became a whistleblower (Video courtesy of The Guardian, Glenn Greenwald and Laura Poitras)

A business partner of Twitter recently said it would no longer provide services to the US intelligence community.

But Mr Hallman says the levels of suspicion are not uniform.

"There are a lot of great parties in Silicon Valley who understand our values well, but there are some sectors that do not understand the intelligence world," he says.

Part of his job is to change that.

"I'm an optimist - I think we will eventually build that trust," he says.

He points to the working relationship between the intelligence community and Amazon Web Services to provide cloud computing as an example of what the relationship could look like.

Back out in the corridor are historical examples of technology developed initially for espionage - early photocopiers and tiny Minox cameras - all once cutting-edge but now ubiquitous.

Now, spy agencies are learning that maintaining the edge on which they rely will require new ways of working.

- Published8 February 2016

- Published3 November 2015

- Published26 November 2014

- Published17 January 2014