Deconstructing Comey's testimony on Clinton emails

- Published

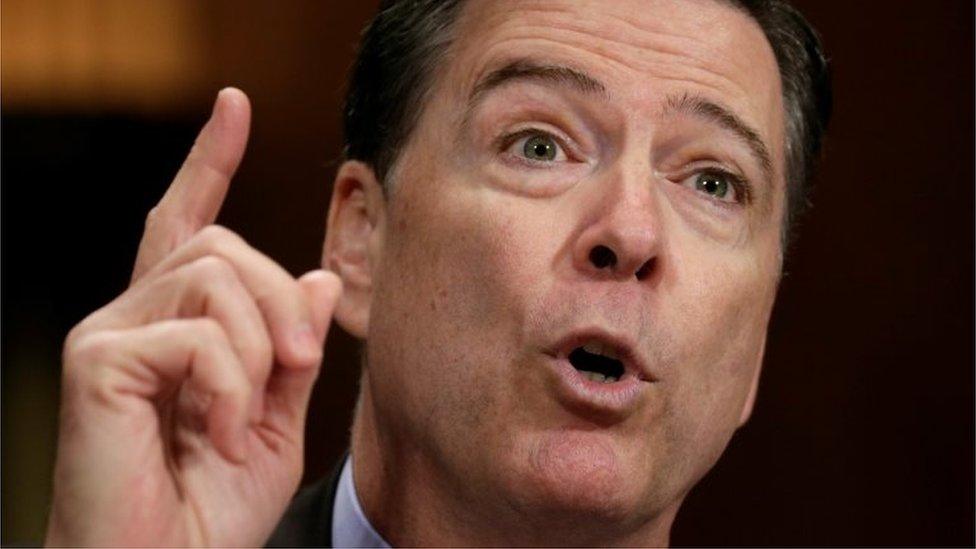

Comey explains why he went public reopening Clinton email probe

FBI Director James Comey has revisited his fateful decision to write a letter informing Congress that he was reopening the investigation into Hillary Clinton's private email server less than two weeks before November's presidential election.

According to, external political analyst Nate Silver, the Comey letter "probably" cost the former secretary of state the presidential election - a view recently endorsed by Mrs Clinton herself.

Mr Comey's Wednesday remarks were in response to a question from California Democratic Senator Diane Feinstein during a Judiciary Committee hearing, and it was one for which the director was clearly prepared. His seven-minute answer was measured yet forceful; polished yet seemingly sincere.

Here's a closer look at what he said - and what it may mean.

Clinton advisor Huma Abedin forwarded some Hillary Clinton emails to her then-husband, Anthony Weiner.

"October 27, the investigative team that had finished the investigation in July ... laid out for me what they could see from the metadata on this fellow, Anthony Weiner's, laptop... What they could see from the metadata was that there were thousands of Secretary Clinton's emails on that device, including what they thought might be the missing emails from her first three months as secretary of state."

Mr Comey first sets out why he thought the emails on the laptop of Mr Weiner, husband of Clinton adviser Huma Abedin, could be so important. There was the possibility that these never-before-seen Clinton messages could be a potential smoking gun - "evidence that she was acting with bad intent," in Mr Comey's words.

If Mrs Clinton, or her aides, had set up her private email server not because of convenience, as they asserted, but to avoid open-records requirements or intentionally break the law, then Mr Comey could have cause to bring a criminal case against the former secretary of state.

"I've lived my entire career by the tradition that if you can possible avoid it, you avoid any action in the run-up to an election that might have an impact, whether it's a dog-catcher election or president of the United States."

Mr Comey is echoing an unwritten rule in the US Justice Department, of which the FBI is a part, that investigators should avoid taking actions that could affect the outcome of an election that is less than 60 days away.

A memo first distributed by the Justice Department in the George W Bush administration and subsequently recirculated by Obama Attorney General Eric Holder instructs government employees to "never select the timing of investigative steps or criminal charges for the purpose of affecting any election or for the purpose of giving an advantage or disadvantage to any candidate or political party".

Following Mr Comey's letter to Congress, members of the Clinton team, including campaign manager Robbie Mook, suggested, external Mr Comey was violating this rule.

"I sat there that morning, and I could not see a door labelled no action here. I could see two doors, and they were both actions. One was labelled speak. The other was labelled conceal."

Here is the heart of what Mr Comey describes as his "painful" dilemma. Once he decided to reopen the investigation, he believed that doing nothing would effectively be active concealment.

In the ensuing days and months, Mr Comey's critics have said silence would not only have been in keeping with Justice Department policy, it would have been the prudent move given that the director did not know what the Weiner laptop contained.

Mr Comey - perhaps because he knew the investigation would leak to the press anyway or possibly because he feared the emails could reveal Clinton misdeeds after she had won the presidency - decided otherwise.

"I stared at 'speak' and 'conceal'. Speak would be really bad. There's an election in 11 days. Lordy, that would be really bad. Concealing, in my view, would be catastrophic, not just to the FBI, but well beyond. And honestly, as between really bad and catastrophic, I said to my team we got to walk into the world of really bad. I've got to tell Congress that we're restarting this, not in some frivolous way, in a hugely significant way."

Media coverage of Mr Comey's statement has focused on the "catastrophic" versus "really bad" dichotomy he constructed. The director tacitly acknowledged that he knew the impact his letter would have on the presidential campaign, but he wanted to let everyone know that the alternative was much, much worse.

If silence meant active concealment, he argued, then the prudent move was disclosure.

Diane Feinstein's question prompted James Comey's detailed answer about his controversial letter to Congress

The last line of this passage, however - that the investigation was being restarted in a "hugely significant way" - is equally important.

At the time of Mr Comey's letter to Congress, many pundits and analysts were saying that the FBI must have found some very critical evidence, given that the director had to have known the monumental impact of his action.

It turns out the evidence wasn't there, of course. That left Mr Comey with the task on Wednesday of convincing the senators, and the public at large, that - knowing what he knew in October - his actions were still justified.

"Look, this terrible. It makes me mildly nauseous to think that we might have had some impact on the election. But honestly, it wouldn't change the decision."

Mr Comey arrives at this conclusion after recounting how his investigative team had found thousands of new Clinton emails, including some that were classified, on Mr Weiner's laptop, but did not discover anything that indicated criminal intent.

He then decided, two days before the election, to send another letter informing Congress that he had ended the investigation with no change in the FBI's original determination not to bring charges against Mrs Clinton.

The entire saga probably leaves Mrs Clinton's supporters more than just "mildly" nauseous.

For Mr Trump's backers, on the other hand, it's much ado about nothing - an attempt, according to the president, to shift blame for electoral defeat away from the Democrats and onto the FBI.

Mr Comey says he wouldn't change his decision, but it's one that will be second-guessed and scrutinised for a very long time to come.

- Published3 May 2017

- Published3 May 2017