How a University of Washington researcher discovered an "information war"

- Published

Comet Ping Pong restaurant has been the target of fake news and malicious gossip on the internet.

University of Washington researcher Kate Starbird's research into online rumours lead her to an information war being waged through a web of highly politicised conspiracy theories.

In 2013, in the time between when two homemade bombs detonated near the Boston marathon finish line and when police cornered and caught bomber Dzhokhar Tsarnaev, a conspiracy theory began to spread online.

Internet sleuths, analysing pictures released by the FBI, said they saw evidence of a false flag attack - proof that the bombing had been staged or carried out by the US government.

University of Washington professor Kate Starbird and some of her research team noticed these accusations on Twitter, since they were studying how rumours spread on social media during events like mass shootings and terror attacks.

While other online rumours would gain traction and die away as facts became clear, the Boston false flag speculation did not abate, even after Tsarnaev and his brother Tamerlan were identified as the bombers.

At the time, Starbird and her team saw the conspiracy theory as something of a curiosity.

"We didn't want to go there," she says. "It just seemed messy."

But after taking a closer look at those rumours, she now says her research suggests there is an "emerging alternative media ecosystem" that is growing in reach, and that may have underlying political agendas.

Researcher Kate Starbird first began exploring social media rumours during the 2013 Boston Bombing

Starting in January 2016, she and her team began mapping sites generating conspiracy theories.

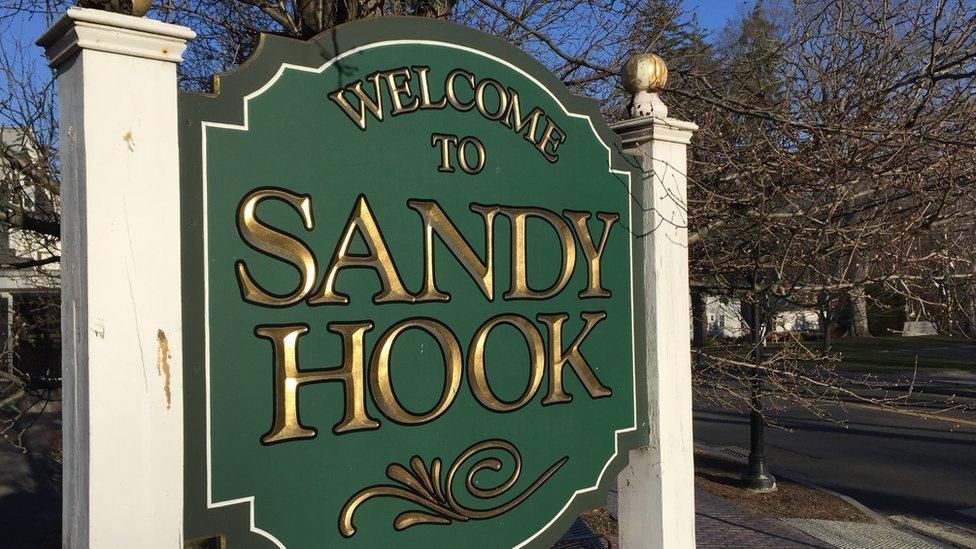

They tracked Twitter reaction to shootings along with references to terms like "false flag" and "hoax" and the websites that used them.

Starbird has dubbed what they discovered the "the information wars, external".

The work, external is nominated for best paper at an international web and social media conference, external in Montreal this week.

Highly politicised alternative narratives to events were being spread by a mishmash of websites: anti-mainstream media sites, anti-corporatist "alt-Right" and "alt-Left" sites, conspiracy-focused White Nationalist and anti-Semitic sites, Muslim Defense sites and Russian propaganda.

"There are different actors," she says. "Some are (acting) for financial motives, some are for political motives. Some people are true believers."

Calling her finding an "information war" is not a nod towards talk show host Alex Jones' alternative news website Infowars, which focuses on Alt-Right and conspiracy theory themes. His site rose to mainstream prominence during the 2016 American election.

But she has written tongue-in-cheek that "this work suggests that Alex Jones is indeed a prophet".

Looking back on their older research, they found hints of similar conspiracy activity around the 2010 BP Deepwater Horizon oil spill, which devastated the Gulf Coast of the US.

In 2016, the university researchers found sites that helped propagate these conspiracy theory tweets were often so-called "alternative media" domains like VeteransToday.com and BeforeItsNews.com.

The researchers also found sites like TheRealStrategy.com, which appeared to be generating automated conspiracy theory tweets with "bots" in order to propagate politicised content.

Many of the tweets had a political element. For example, a mass shooting might be blamed as a "false flag" by the US government, with speculation that the attack was planned to to gain support for gun control.

Tweets also included hashtags linked to online political conversations like #obama, #nra, or #teaparty.

While belief in certain conspiracy theories, external can be sometimes linked political beliefs, Starbird's research suggested that political content on sites pushing the alternative narratives was less about left-wing versus right-wing - no political leaning was immune - but instead had a broad anti-globalist bent.

There was also plenty of anti-vaccine, anti-GMO, and anti-climate science content, as well conspiracies about the world's wealthy and powerful citizens.

Starbird's research points to an intentional use of disinformation to muddle thinking and "undermine trust in information just generally".

She says big questions remain, like who might be behind any possible intentional disinformation campaigns and to what extent these messages are coordinated.

But she says she is concerned that as these fringe theories gain traction in the public sphere "it is not healthy for society

"When there's no shared reality, there's no set of facts, society at large can become easily manipulated," she says.

- Published2 April 2017

- Published21 February 2017

- Published31 October 2016