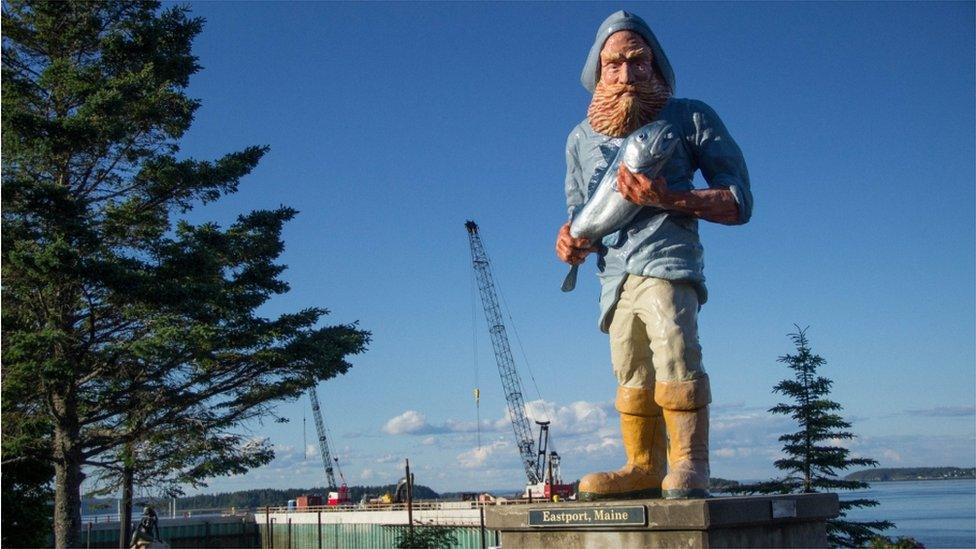

The coastal Maine town that shipped cows to Turkey

- Published

Eastport in Maine has survived for more than 200 years by changing how it lives off the sea. Its next act is no different.

Just a three-minute boat ride from Canada, Eastport earned its name because it's the easternmost port, and city, in the US,

From a peak population of just more than 5,000 in the year 1900, the city has dwindled to about 1,300 residents. Today, a handful of restaurants dot its tiny downtown. During winter, they're mostly closed.

Eastport also sits in Washington County, one of the poorest parts, external of the United States, with high unemployment and opioid abuse.

"We've had a lot of deaths from overdoses. Five people that I knew last year died or their kids that I know died," says local ship pilot, Captain Bob Peacock. "It's horrible."

A century ago, it was a different story in Eastport. It was the sardine capital of America. Regular ferries ran from here to Boston.

The Tides Institute & Museum of Art, external in downtown displays striking photos by Lewis Hine from that era, including of three boys, ages seven to nine, standing in front of a pile of sardines.

"They would be pulled out of school. There would be a whistle blown, and there would be whistles for different factories," says Kristin McKinlay, who co-founded the Tides Institute with her husband.

"They'd hear their whistle and then they would run down the hills, downtown with the knives with them and then work until the fish were gone."

Downtown Eastport

By the 1980s, Eastport's sardine industry was diminished but still flourishing.

"They were also making cosmetic glitter from the colourful slime off the back of the scales, it's called pearl essence. There were three pearl essence factories here," says Chris Bartlett, a commercial fishing specialist with the University of Maine who moved to the area in the late 1980s.

Eventually, sardines, and other fishing businesses dried up, external. And the town did, too. "Our elementary [primary] school was built to house 250 students," Bartlett says, "We now have 86."

The area still does have salmon farming and lobster fishing.

And, crucially, the city has its port.

A few years back, the Eastport Port Authority got an unusual phone call. A Texas company was looking for a place from which to ship cows to Turkey. Pregnant cows.

"I said: 'They want to ship pregnant cows out of Eastport? How are they going to do it?'" says Chris Gardner, the port's director.

The answer - cows would be shipped in boxes that can hold 14 at a time.

"At this point in time, I honestly thought it was half a joke. But I realised it wasn't," Gardner says,

The port said yes, without fully knowing how they'd manage to do it.

For three years, the city was booming again. Then in 2014, cow exports collapsed when southern Turkey became too unstable.

"It's funny, in an international situation when you're a port like this, what happens anywhere in the world affects you," says Peacock. "And you figure that out pretty quick when your income comes from piloting ships, and all of a sudden there are no ships because of a war in Syria."

Ship pilot Bob Peacock guides vessels into the port of Eastport. His business was hurt when the shipment of cows to Turkey stopped in 2014

So, what is Eastport going to do? Build off the cows.

"The cows... illustrated that new things can happen," says Gardner. "Here we have, literally, the deepest natural seaport, not in our county, not in our state, but in the nation - in the continental US there isn't a port any deeper.

"And with all the changes that are taking place in global shipping, for a rural county who is just looking for a way out, well why couldn't this be that way out?"

Eastport is also the closest American port to Europe, and already ships a lot of wood pulp from Maine to Europe and Asia, about 40 ships a year. Many locals are looking for more activity at the docks.

But the city is also isolated, tucked away in the extreme north-east corner of the country. And some residents aren't convinced by the sales pitch.

"I'm not sure that it's realistic," says retired teacher Gregory Noyes. who runs the Kilby House Inn, one of three bed-and-breakfasts in Eastport.

"There's no way, as far as I can tell, to get goods out of Eastport. There's not a major highway, there's not a rail service. There needs to be a way to get goods and services in and out easily. And I don't see the practicality of that, I really don't."

Many here share that concern, including people working around the port. Then came Donald Trump and his talk of rebuilding America's infrastructure. Peacock liked that.

"I believe, when he [Trump] talked about infrastructure, I think most people in this area understood exactly what he was talking about," says Peacock.

That's because one of Eastport's piers collapsed three years ago. "It created a tsunami in the harbour," he says, pointing at the windows of nearby buildings that got hit by the wave.

Eastport gets some vacation traffic, but not much partially due to its remoteness - it's the last city along the northern Maine coast

It happened in the middle of the night, and only one person was injured. But it's costing more than $15m (£11.6m) to fix. The federal government is picking up roughly half that tab, and locals hope Washington will keep investing in their community.

"We're going to be pushing on that," says Gardner. "Because quite honestly, with the deepest natural seaport in the United States of America, how do you not connect that to a railroad? Especially when it's in one of the poorest counties this nation has."

"This asset exists, there is the political will and climate to see this port grow, and all we need is that infrastructure," he says.

But the question is, are Washington politicians, and President Trump, willing to invest?

The World is a co-production of the BBC World Service, PRI and WGBH. This piece is part of the PRI's The World series 50 States: America's place in a shrinking world. Become a part of the project and share your story with us, external.