My Canadian immigrant story: From Chile to Montreal

- Published

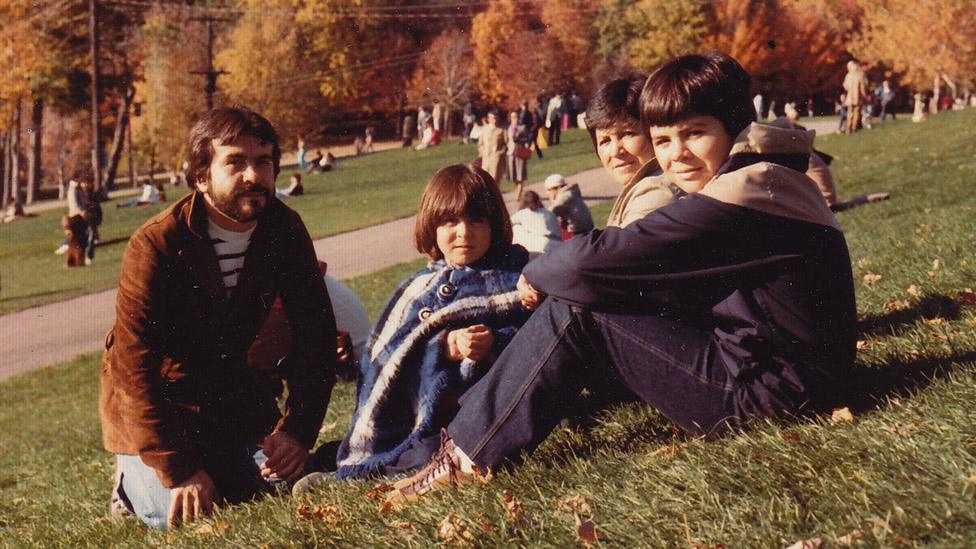

Karin Arroyo and her family in Montreal

The BBC is running a series looking at the immigrant experience in Canada and the ties immigration creates between nations. In this third story, we look at growing up in a new country.

Karin Arroyo's family arrived in Montreal in 1979 from Valparaiso, Chile.

The young family was fleeing the Pinochet dictatorship in the South American country, though politics were lost on the three-year-old who was just excited to see her father. He had landed in Canada six months before.

Edmundo Arroyo-Fuentes had travelled to Montreal in October 1978, telling his extended family he was heading to Spain and not Canada, where he would seek political asylum.

Chileans who opposed Augusto Pinochet had learned to be cautious when seeking asylum after the brazen 1976 assassination of Orlando Letelier.

Letelier, a prominent opponent of military rule in Chile, was killed in a car bombing on the streets of Washington DC by agents linked to the Pinochet regime, suggesting his power extended beyond Chile's borders.

So the Arroyo family - Karin, her mother and her eight-year-old brother - waited for news. A call finally came. They were to join their father.

Montreal felt like a welcoming city in the 1980s

For three-year-old Karin, there was the excitement of taking her first flight, of seeing the new apartment and its high ceilings - "it seemed almost magical" - and fridge full of food.

She recalls her father wanting to show his two children snow for the first time but that most had melted by that spring.

He'd found a patch of it behind a local church in a corner where the sun never hit.

That patch wasn't much - icy and granular, patched grey with pollution.

"And my dad is so happy and so proud to show us this little thing of snow and it's like the dirtiest thing I've ever seen in my life," she recalls.

"Of course when it finally ended up snowing several months later - oh my god it's fantastic. It's white and fluffy."

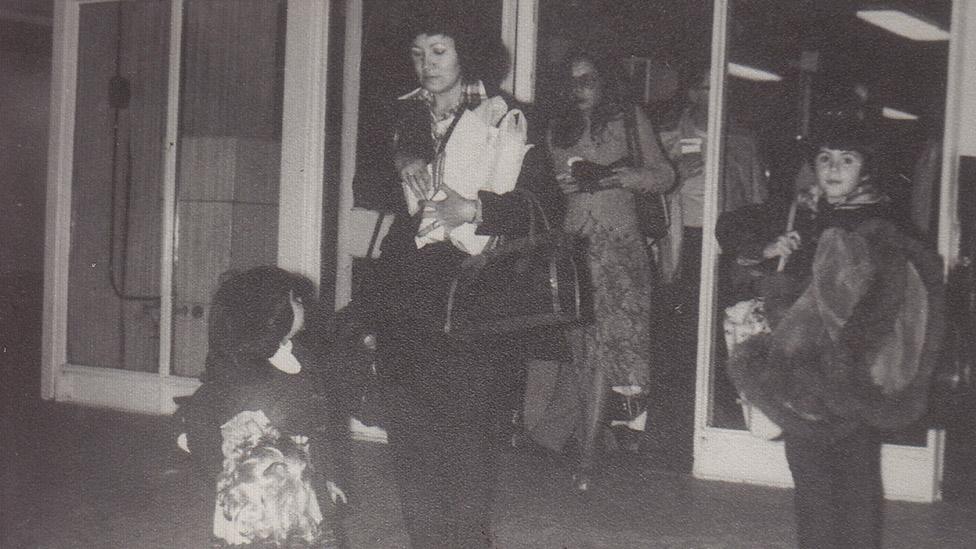

The family arrives in Montreal in 1979

In Montreal in the 1970s, the Chilean expat community was booming. Thousands of Chileans came to Canada after General Pinochet toppled President Salvador Allende's Marxist government in a 1973 military coup.

Three years after Pinochet's death, the city's Chilean community helped fund a monument, erected in 2009 in a city park, commemorating Allende.

Karin recalls the community "just kept going as if they were still living in Chile, fixing the world still".

"Fixing the political situation in Chile although they weren't really living there anymore.

"They'd always talk about the dictatorship and what can be done and how they could regroup and try to fight it from the outside".

Edmundo Arroyo-Fuentes was the only family member who had been involved in politics in Chile.

But he and his wife kept a certain distance from other Chilean expats, though they had some close Chilean-Canadian friends.

"In my view it was necessary and important to learn French, to assimilate into the new society into which we had to blend," he says.

In the first months, they went to now defunct immigration and orientation centres run by the provincial government - known by the French acronym Cofi - which Arroyo-Fuentes calls "fantastic", saying it was a rich cultural experience that eased their integration into Quebec society.

Karin says: "They would take them to the Old Port to go to the 'boite a chanson', they'd put on these plays.

"I mean, they'd listen to things like Gilles Vigneault, Paul Pichet and all these musicians from the folk era of the 70s".

Karin Arroyo's family fled the Pinochet regime in Chile

Chileans weren't the only new arrivals in that era.

In the late 1970s, 60,000 refugees from Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia were resettled in Canada, many moving to large cities like Toronto and Montreal.

Some 20,000 Ecuadorians also came to Canada in the early 1970s, joined by many others from various Latin and Central American countries.

"It was just a mix of kids from all over the place," Karin says.

She remembers the cultures mixing along one of the city's main thoroughfares, St-Lawrence Boulevard, once a symbolic, unofficial dividing line between Montreal's French- and English-speaking populations.

"It was one of these things - 'oh, you're an immigrant as well, where are you from, when did you arrive?'" she says.

"It was that curiosity. It didn't matter where you came from, you always had that story to tell and people were curious, which was one of the great things about Montreal."

"It's a big town but at the same time it's a small town and everyone wants to know your story, and that's something I didn't see elsewhere."

Her father remembers how difficult it was to get news from Chile and family there in the early years without the internet and with the exorbitant cost of long-distance calls.

"Since we started returning to Chile, traveling as visitors, we realized we were strangers in our own country, both with our families and among our friends," he says.

Karin says despite her positive experience, she felt uprooted, not knowing whether she belonged in Montreal or Chile.

She was envious of friends who didn't appear to struggle with their dual cultural identities and told herself she wouldn't do the same when she had her own children.

Now, she says: "Chile is where my roots are, but my heart belongs to Montreal.

"I now live in France, with a family of my own, forcing immigration upon my children even though I had promised myself to never do it."

- Published16 December 2016

- Published8 June 2017

- Published18 August 2017