Trump's 'new' Iran policy and the difficulties ahead

- Published

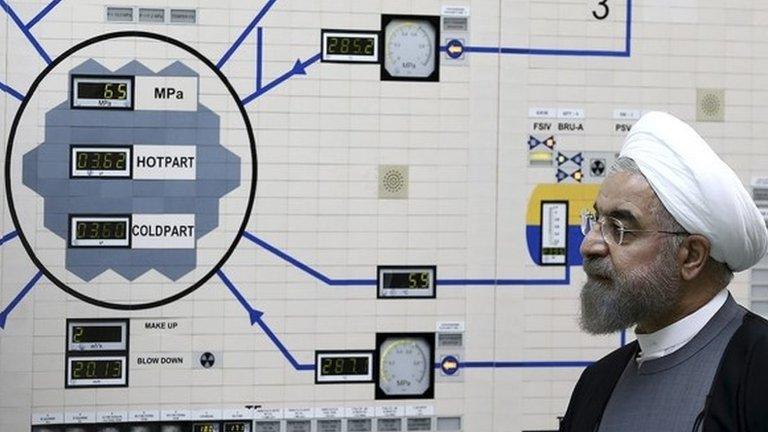

After railing against it for years, President Trump announced he would refuse to recertify the Iran deal

In setting out his new Iran policy, President Trump painted a stark picture of Iran as a brutal and manichean power, driven by a revolutionary ideology and eager to confront the US and its allies at almost every turn.

In contrast to what he clearly sees as the lax approach of the Obama administration, Mr Trump wants to double-down on Iran - enforcing the nuclear deal more effectively and countering its growing regional influence.

But beyond the tough rhetoric intended to please his own political base, what actually is new about Trump's new Iran policy? To what extent is it a departure from the Obama years? And what might its likely consequences be?

Given Mr Trump's vehement opposition to the Iran nuclear deal - the JCPOA as it is known - it is surprising that, for now at least, the US is not walking away from the agreement. The president could so easily have restored nuclear-related sanctions without having recourse to Capitol Hill.

Instead he has placed the fate of the nuclear agreement in the hands of Congress.

He is clearly seeking - and key Congressional leaders are already working on - amendments to US law that would automatically restore sanctions if Iran took specific actions known as trigger points. There is even a strong suggestion that he wants Congress to make the expiry of certain restrictions under the agreement - the so-called sunset clauses - irrelevant by again using trigger points to automatically restore sanctions should Iran re-start activities once the JCPOA restrictions have been lifted.

What if anything may be agreed in terms of US legislation is a future story. But just how extraordinary such a step would be needs to be noted now. The US would effectively be using its domestic law to try to re-write a multilateral agreement. There could be diplomatic difficulties ahead. It could create a potential rift between the US and its allies, and further tensions between Washington on the one hand, and Moscow and Beijing on the other.

It also raises questions about how far a US administration's word can be trusted when it concludes an international agreement. What sort of signal does it send to a country like North Korea that is being encouraged to return to the negotiating table by Mr Trump's own secretary of state?

Mr Trump painted a bleak picture of the nuclear deal's value, asserting at one point that it was enacted, and nuclear-related sanctions were lifted, "just before what would have been the total collapse of the Iranian regime". Few will recognise this situation as reality. Instead the deal was negotiated at a time when there was a very real possibility of a war between Israel, and possibly the US, on one side and Iran on the other. The nuclear deal averted this and placed constraints on Iran's nuclear activities.

Certainly Mr Trump was fair to cite the agreements shortcomings. Ballistic missiles were not covered and Iran's missile programme continues apace. Many of the agreement's restrictions will indeed expire in time. Several countries hoped to address some of these problems at a later date but it is far from clear that this moment should be now.

Iranian technicians at the Isfahan Uranium Conversion Facilities, south of Tehran, in 2005

Mr Trump cited violations of the agreement by Iran but failed to mention that when concerns have been raised under the JCPOA's dispute mechanisms Iran has pulled back on its questionable actions.

The decision to keep the nuclear deal in place for the time being raises a question over whether Mr Trump is creating an opportunity to strengthen the deal or weakening it.

Of course, nuclear matters are only one of the problems between the US and Iran. Many of the advocates of the nuclear deal would agree with Mr Trump about Iran's wider activities in the region.

Mr Trump speaks as though the Obama administration had not sought to impose sanctions against Iran for a variety of misbehaviours - support for terrorism, infringement of its own people's human rights and so on. He says that sanctions will be stepped up, especially against Iran's ideological and military elite, the Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC). But the newness of the Trump policy seems to be a matter of rhetoric and degree, rather than substance.

Mr Trump seeks to make an explicit link between what he sees as the failing nuclear deal's relaxation of restrictions on Tehran and its wider activities in the region. It certainly has more money at its disposal. And here too he has a point.

Just before Mr Trump's speech a former state department official, Jon B. Alterman - now at the Center for Strategic and International Studies - explained to me the previous administration's thinking: "They focused on what they saw as the most strategically threatening piece, the nuclear one. This is in part because they had other tools to deal with other aspects of Iranian behaviour, and in part because they thought that a gradual opening to Iran would empower domestic constituencies there that wanted Iran to act like a more normal state in the region."

That didn't really happen. Some would argue that Iran does indeed have a more moderate government today, in part due to the economic benefits of the nuclear deal. But few would say that the hard-line elements of the IRGC have significantly moderated their behaviour abroad.

President Trump and Iran's President Rouhani traded insults at the UN

And this brings me to a more fundamental issue, the changing role of Iran in the region. The US inadvertently set this process in motion by removing Saddam Hussein's regime in Iraq, which had always been a strategic counter-weight to Tehran. Since then, Iran has taken every advantage of the chaos in the region to further its own ends. Was this all malign intent on the part of Tehran or simply the furtherance of its strategic goals? Where is the line to be drawn?

This matters, because the region is now entering a critical and even more dangerous phase. With the so-called Islamic State close to defeat, a battle is under way in Iraq and Syria for a distribution of the spoils. In Iraq, Iran has significant influence over the Shia-dominated government and many militia forces loyal to its point of view. In Syria, it is among the chief backers of the Assad regime, which puts it and its proxies in direct opposition to US-backed groups. Is this really the time to be provoking even greater tension between Washington and Tehran? Or is it a moment to combine firmness with at least the opportunity of dialogue?

Diplomacy - in the much over-used phrase - is the art of the possible. The nuclear deal, with all its imperfections, was the only one that was possible at the time.

The deal limps on, perhaps weakened but not yet fundamentally undermined. The parameters of Mr Trump's wider effort to contain Iran are yet to be spelt out in detail. His speech represents above all an uneasy compromise between the views of the president and those of his most senior officials and military advisers - all of whom want to see a tougher stance towards Tehran, but who, equally - to a man - have backed the nuclear accord despite all its imperfections.

- Published13 October 2017

- Published3 October 2017

- Published17 May 2017

- Published22 May 2017