Has the US forgotten about World War One?

- Published

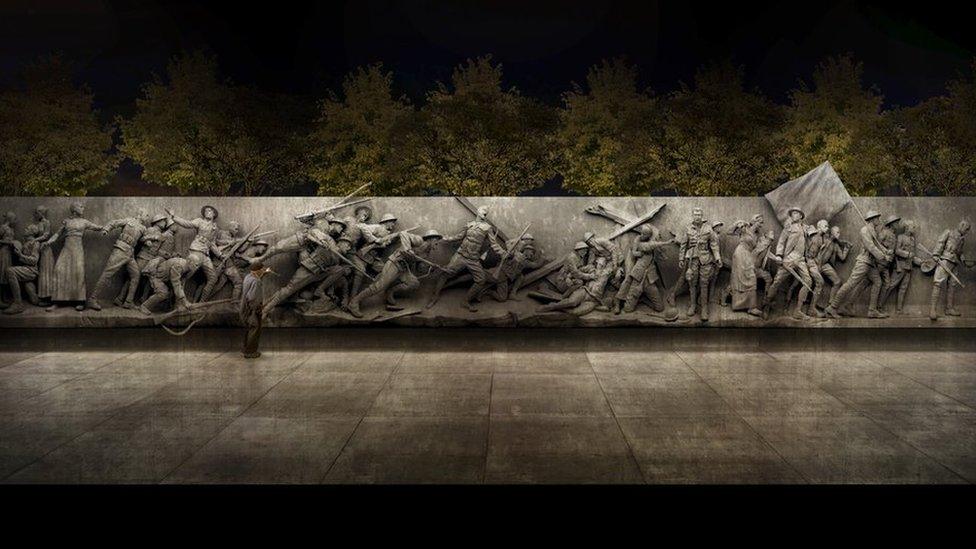

An illustration of the WW1 memorial concept, scheduled to be completed by late 2018

There are no World War I veterans left alive in the US, but a century after the conflict that reshaped the world, ground has broken on a new monument in Washington, DC, to the 4.5 million Americans who served.

The US entered the war in 1917 - almost three years after European powers had been bludgeoning themselves to near destruction. Some 53,000 US soldiers were killed in combat, according to the defence department, while 64,000 died off the battlefield, including deaths from the influenza epidemic. Another 200,000 were wounded.

At the time, few Americans wanted to join a conflict largely thought to be pointless and irrelevant. Despite its profound impact on what became the "American Century", World War I remains a marginal war for many in the US.

"The Great War" was overtaken in the national consciousness by the Great Depression and World War II, says Edwin Fountain, vice-chairman of the WWI Centennial Commission. The commission has been authorised by Congress to build the new memorial in Washington, DC, as well as increase awareness of the war.

Gun crew from the 23rd Infantry, firing during an advance against German positions 1918

"The Centennial is the last best opportunity to teach Americans that World War I was in fact the most consequential event of the 20th Century," he says. "It had effects that we live and struggle with today, overseas and at home."

"The debate about the role of America in the world, the balance between national security and civil liberties, the place of women, African Americans and immigrants in our society - all those issues were vigorously discussed during WWI.

"You cannot contribute to those discussions today without understanding our historical roots."

The memorial is by no means the first monument to honour American veterans of World War I, including hundreds of local monuments and tributes across the country.

Officers of the "Buffalos," 367th Infantry in France in 1918

A domed temple on the National Mall commemorates the 26,000 veterans from Washington, DC, who served in the Great War, including 499 who lost their lives. Congress considered re-designating it as a national memorial, but DC residents resisted the plan.

The new memorial fills a void, says Fountain. "We were, by omission, sending a message that their service and sacrifice was not as worthy of [national] commemoration."

WWI Centennial Commissioner John Monahan says any earlier effort to erect a national monument would have been politically untenable. On the war's 50th anniversary in 1968, the US was facing tremendous social and political upheaval.

"We had more than half a million troops in Vietnam, which fractured our society," he says. "To a large extent it broke our military, spiritually. It took us a generation to recover from that."

Americans have moved away from the notion "the warriors and the war are one and the same," says Monahan. "We are now able to distinguish honourable service of the military from the political tumult that may result from a decision to go to war."

A ruined church in France after US troops drove German troops out of the town

There is also a 217-ft high national memorial tower and museum in Kansas City, Missouri, which offers a global history of the war and a large collection of artefacts. Dr Matthew Naylor, the president and chief executive of the Missouri museum, says he welcomes a new national memorial in Washington.

"Washington is the place where national memorials are, and it's right that there ought to be the opportunity to pay respects and remember those who served in World War I," he says.

He says the construction is further evidence of a renewed interest in "the founding catastrophe of the 20th Century". The number of visitors this year to the National WWI Museum and Memorial in Kansas City has more than doubled since the start of centenary commemorations in 2014.

America's enthusiasm for war memorials in Washington gathered pace in the 1980s, with the construction of the Vietnam Veterans Memorial on the National Mall. That was followed by the Korean War Veterans Memorial in the 1990s. A plaza with 56 pillars and a pair of triumphal arches to commemorate those who served in World War II opened in 2004.

Medical corps remove a wounded soldier from Vaux, France

An architect, Joseph Weishaar, 27, beat 350 other contestants in an international competition to design the World War I memorial.

His vision, "Weight of Sacrifice", aims to transform Pershing Park, a small concrete area built in 1981 just a block from the White House on Pennsylvania Avenue. The park already contains a memorial to Gen John "Black Jack" Pershing.

Pershing commanded the American Expeditionary Force in one of the bloodiest campaigns in US history, the Meuse-Argonne offensive, which killed more than 26,000 American soldiers but effectively ended the war.

The statue, as well as a disused pool and fountain, are part of Weishaar's plans.

The memorial will be built around the existing water features in the park

"It brings purpose back to the park without having to redo everything. We can give it new meaning and new life," Monahan says.

But there have been some objections. The Cultural Landscape Foundation says the design would destroy one of the most significant examples of urban landscaping by the celebrated modernist architect Paul Friedberg. His other projects include Peavey Plaza, in Minneapolis, which is listed on the National Register of Historic Places, and New York City's Battery Park City.

Nevertheless, the monument should be completed in time for the 100th anniversary of Armistice Day on 11 November 2018. It's expected to cost between $30-35m, raised from private donors.

A generation that no longer has a voice will be properly remembered, says Monahan.

"I do not in any way regard this as too late," he says. "The fact they are no longer here to speak for themselves makes it imperative that we, who are, make it right.