A mental health scandal haunting America

- Published

WATCH THE DOCUMENTARY: What are we going to do about Tyler?

The scandal of a US teenager locked up for almost four years without trial revealed serious failings in Mississippi's criminal justice system. But Sarah Smith, the reporter on the BBC News-ProPublica investigation, says America's mental health crisis goes much deeper.

When I arrived, the sheriff was wary of me.

I was a visitor to his rural Mississippi county; worse, I was a reporter from New York City.

He summed up his scepticism this way: Every time Mississippi made national news, it seemed like the reporters managed to find the one toothless person in the vicinity and shove him or her in front of the camera.

The sheriff had a point. And I had a challenge to conquer. The story I was onto was not going to flatter Mississippi. But I did promise him I would not go searching for the toothless.

Read ProPublica's in-depth investigation, external

I had come to write about the mentally ill in Mississippi, in particular those who wound up in jail, accused of often serious crimes but denied - for months and even years - the basic legal requirement that they receive a mental evaluation. Such evaluations - whether the defendants were sane at the time of the alleged crime and now competent to stand trial for those crimes - would profoundly shape the rest of their lives.

Tyler Haire, 16, after his arrest

Tyler Haire was one of those I wanted to write about. He was 16 when he was arrested for stabbing his father's girlfriend. She survived, but Tyler, with a mental health case file thick with diagnoses, went to jail. He waited nearly four years for the evaluation a judge ordered be done as soon as possible.

Neither the sheriff in Calhoun County nor Tyler's family knew I was coming. But they let me into their homes, their jail, their lives. Then they let me come back, again and again.

They and others in Mississippi - families, sheriffs, mental health professional, politicians - wanted their stories of deep frustration told.

It was, they felt, a Mississippi embarrassment that would be helped by greater, even national attention.

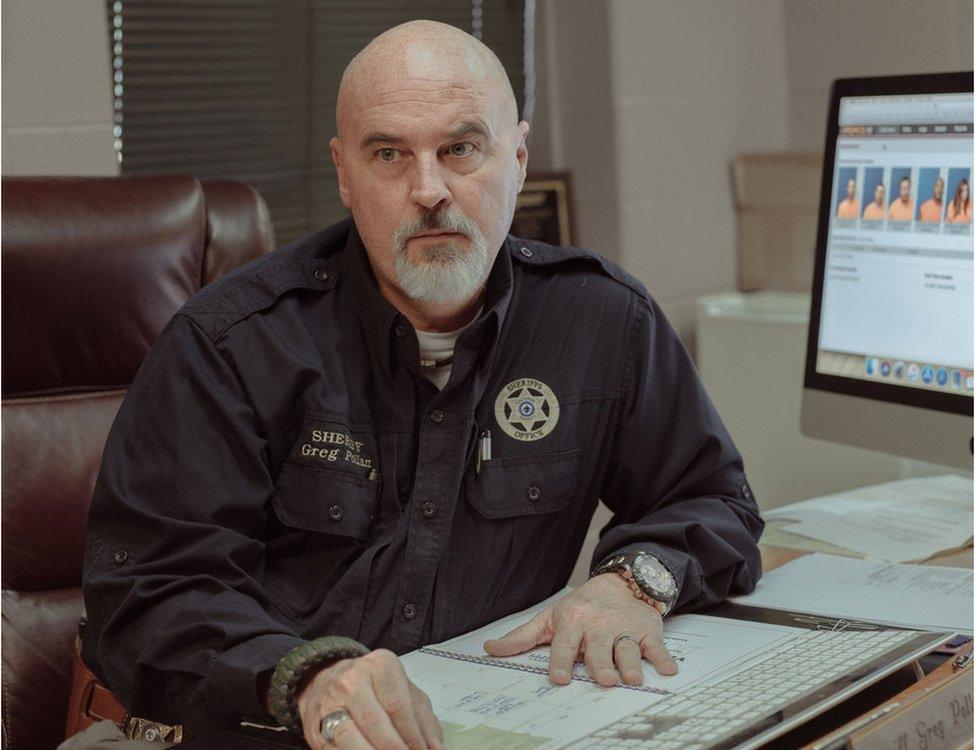

Calhoun County Sheriff Greg Pollan: "This is a national problem"

I soon learned that it wasn't only the accused who sat waiting in jail. The state's mental health resources were so scarce that families saw troubled loved ones who needed hospitalisation wind up behind bars simply for want of an available bed in a treatment facility.

One sheriff had a military veteran in his jail a few years back. The veteran hadn't committed any crime. He was in jail waiting for a bed at a state hospital or a crisis centre. The Veteran's Administration hospital let him walk out. His family had had him involuntarily committed. The man hanged himself in the jail cell. It was the first time the jail staff had ever lost someone like that.

The mentally ill have lost lots in the last decade in Mississippi. Hospital beds. State employees devoted to care. Local crisis centres. Options of all kinds as state budgets have shrunk - first by the national financial crisis, then in a sustained series of state scale-backs.

Mississippi State Hospital at Whitfield has only 15 mental health beds for defendants awaiting trial

The daughter-in-law of the woman Tyler stabbed had lost a brother to suicide. She had walked up to his house and saw him hanging there. He had a history of mental illness and self-harm. She had tried to get him help, trying to get him committed and begging local police officers to go check on him. She had a voicemail of him threatening suicide. He was 33 when he went ahead and did it.

So, today, she mourns him, and helps care for her mother-in-law, a casualty of a struggling system of care and justice.

It didn't shock me, then, when Bridgett, the camera-shy mother of Tyler, told me she too had been hospitalised for her own mental health problems.

Bridgett Haire, Tyler's mother, also suffered mental health problems

"It's too late for me and Tyler," she said to me more than once.

I couldn't honestly tell her otherwise.

But maybe it's not too late for others.

Mississippi, the Calhoun County sheriff knows, is not alone in its problems. States across the country are failing the mentally ill, including those in their jails and prisons. It's a shared shame. My story is an attempt to make better care a shared obligation.

Follow Sarah Smith on Twitter @sarahesmith23, external