Why did the US leave the UN Human Rights Council?

- Published

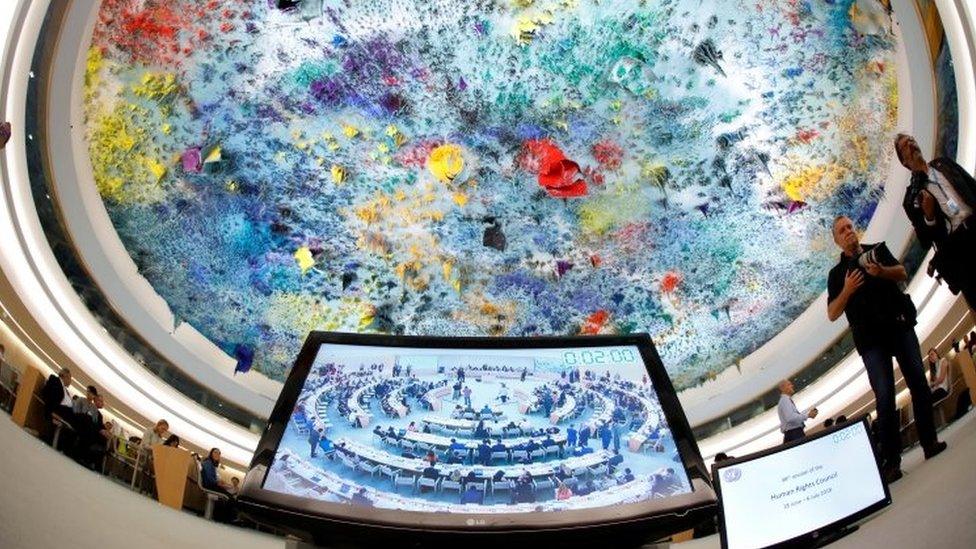

The council meets at least three times a year and reviews UN member states' rights records

The US withdrawal from the UN Human Rights Council was not unexpected but still disappointing for many of Washington's fellow member states serving on it.

Many had hoped, as they had with the Paris Climate accord and the Iran nuclear deal, to persuade the US that a multilateral approach to the world's biggest problems was worth sticking with.

UK Foreign Secretary Boris Johnson came to the council's opening session this week. His speech echoed some of Washington's concerns about the council's focus on Israel, but his overriding message was one of commitment to the council's work.

America's best friend across the Atlantic was in effect advising Washington to turn back from the brink.

Haley: Council has been a protector of human rights abusers

The pleas, as with Iran and climate, did not work.

The US ambassador to the UN, Nikki Haley, did not mince her words announcing the decision, calling the council a "hypocritical and self-serving organisation".

What's gone wrong?

Most UN member states would not use such blunt language, but many do share US concerns.

The council is the world's top human rights watch dog but its current 47 elected member states include Saudi Arabia, Egypt, Venezuela and the Philippines, akin, some critics might say, to the fox guarding the henhouse.

This is a problem the UN has struggled with for many years.

More than a decade ago, the UN under Kofi Annan undertook a major reform programme and top of the list was the then UN Human Rights Commission, which had been widely criticised as politicised and ineffective.

The outcome was the new UN Human Rights Council, with 47 member states elected by their peers in the UN General Assembly.

Each candidate was required to demonstrate a good record on human rights. Each elected member can be expelled for transgressions.

"Under this new system," Kenneth Roth, executive director of Human Rights Watch, said at the time, "countries with poor human rights records like Saudi Arabia will never have a seat on the council again."

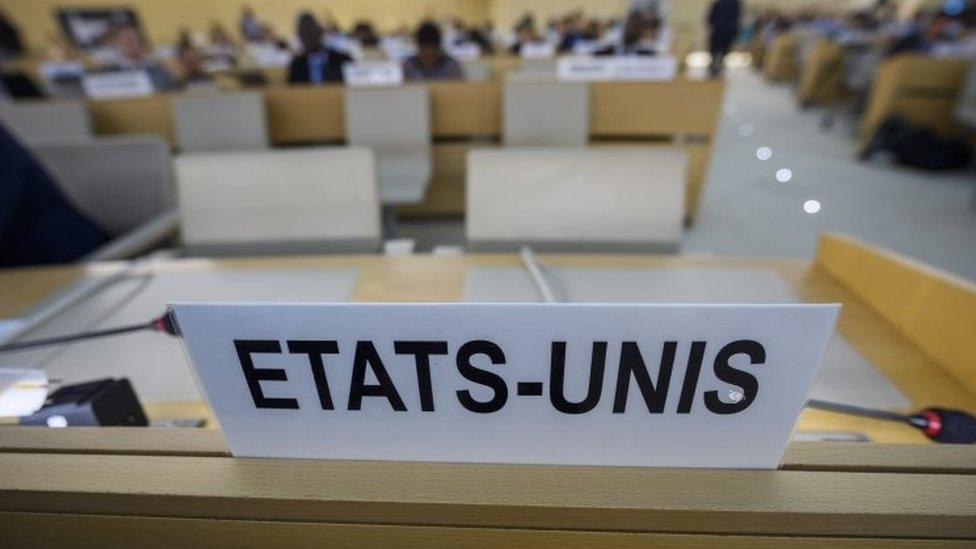

The US seats are now empty at the Geneva-based organisation

Clearly that optimism was misplaced.

The process of becoming a voting member of the council is more rigorous, but the politicisation in which regional neighbours, or likeminded regimes, support each other continues.

Short of allowing certain nations (sure to be the most powerful, as with the permanent members of the UN Security Council) to simply choose which countries are fit to protect human rights, it is hard to see how the system could be improved.

And then there is the Israel factor.

Israel has, alone among nations, the dubious honour of regular scrutiny by the council of its activities in Gaza and the Occupied Territories.

The US and Israel think this is unfair, so too do some European countries such as the UK.

But their voices are outnumbered by countries which firmly believe that Israel must be permanently held to account.

Achievements

All of this wrangling might be academic if the UN Human Rights Council was merely, as some critics allege, a politicised talking shop in which nothing really gets done.

But that is not the case.

In 2017, the UN council authorised an urgent fact-finding mission to investigate alleged rights abuses in Myanmar

US diplomats this week suggested the council had ignored violations in North Korea. In fact, in 2014 the council published a detailed, and searing, report into North Korea, and has kept the spotlight on the country ever since.

Year after year, human rights defenders from all over the world come to Geneva, bringing with them carefully documented cases of the persecuted, the abused and the violated.

Sometimes their efforts are in vain but sometimes, with the active support of member states, action is taken.

In 2017, the council made some significant decisions: among them a fact-finding mission on Myanmar (Burma), an investigation into renewed violence in the Democratic Republic of Congo and, after much debate, a team of experts to investigate alleged war crimes in Yemen.

The Commission of Inquiry into Syria has forensically investigated the conduct of the conflict since the beginning.

Its evidence will very likely lead to prosecutions for war crimes, something those involved in conflict resolution say is vital to create sustainable peace.

The council deals with issues as well as countries: it has been instrumental in promoting the rights of those with disabilities, for example, or of the lesbian, gay, bisexual and trans communities.

So although there is widespread regret that the US is leaving, no-one is likely to follow Washington through the exit door.

Instead there is expected to be more discussion of reform and of the tricky Israel issue.

Meanwhile the council will continue its painstaking investigation, and publication, of human rights situations from South Sudan to Belarus, to Iraq, of the lives of women in Afghanistan, or children living in poverty in some of the world's richest countries.

That, as one human rights defender put it, is perhaps the council's biggest strength: it shines a spotlight on some of the world's worst injustices, meaning that "no-one can say they didn't know".

- Published19 June 2018

- Published9 May 2017

- Published30 December 2016

- Published6 June 2017