Viewpoint: How a hug sparked debate on race and forgiveness

- Published

Brandt Jean embraces his brother's killer in court

A striking display of compassion from the brother of a murder victim to his killer was, to some, a heart-wrenching example of empathy. But to others, it was a painful example of African Americans forced to respond to acts of violence with understanding, writes Barrett Holmes Pitner.

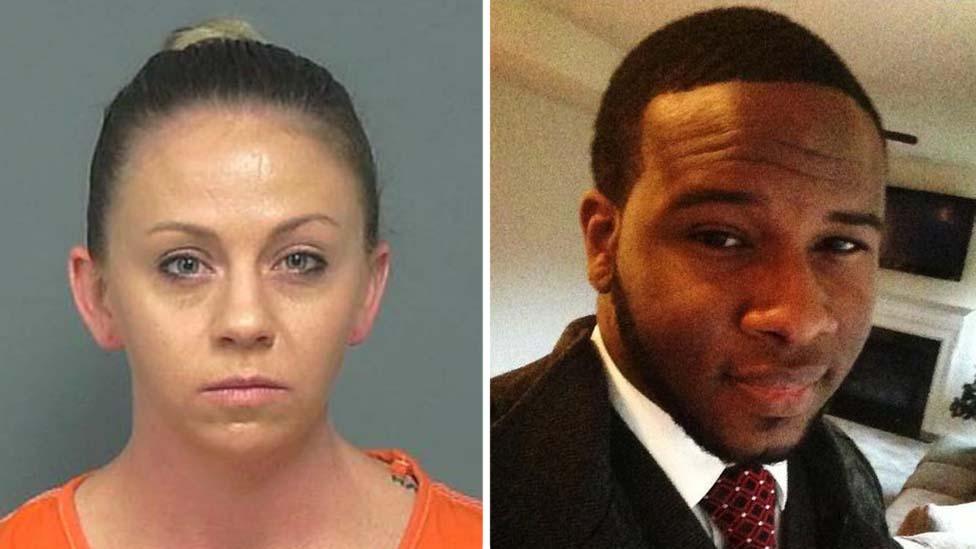

On Wednesday, former Dallas police officer Amber Guyger, 31, who is white, was sentenced to 10 years in prison for the murder of her neighbour Botham Jean, who was black. She will be eligible for parole in 5 years.

Guyger's conviction was seen as a moment of justice for many observers since it is still relatively rare for police officers to be convicted of unlawful killings in America, yet many onlookers also thought her sentence was too lenient. However, the true shock occurred as Guyger received a profound - and controversial - amount of compassion from her victim's family and the judge.

Following Guyger's sentencing, Jean's 18-year-old brother Brandt took the stand and said "I forgive you" and "I love you as a person and I don't wish anything bad on you," before leaving the stand so that he could embrace Guyger.

Their hug lasted nearly a minute as those in the courtroom openly wept from this stunning show of compassion.

Amber Guyger is escorted from the courtroom after being found guilty on Tuesday

Some seasoned court commentators described it as the most powerful moment they had ever seen in a courtroom. And it generated headlines all around the world.

Allow X content?

This article contains content provided by X. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read X’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

After Guyger and Brandt Jean's embrace, Judge Tammy Kemp, who is black, left her judge's bench and also embraced Guyger. Kemp gave Guyger a Bible and the two of them prayed together before Guyger was led away from the courtroom.

In most situations, compassion and empathy do not prompt heated debates, but in the US, the actions of Brandt Jean and Judge Kemp have rekindled a complex conversation about race and inequality. Some observers celebrated the humanity on display in the courtroom, and others questioned if it is just for African Americans to repeatedly take the moral high ground without an exception of reciprocity across America's racial divide.

Allow X content?

This article contains content provided by X. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read X’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

Allow X content?

This article contains content provided by X. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read X’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

Allow X content?

This article contains content provided by X. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read X’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

Frequently, African American communities have responded to terror by expressing compassion and forgiveness to the perpetrators of terror, and have often invoked their Christian faith as the ideological foundation for their acts of forgiveness.

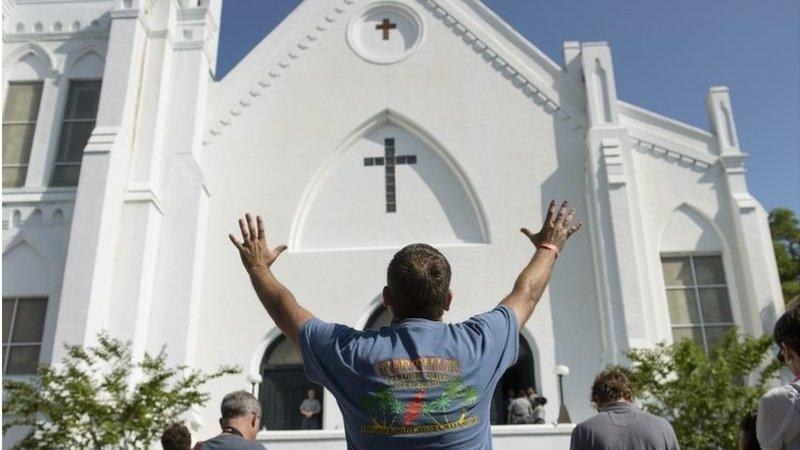

Following the attack on Emanuel AME Church in Charleston, South Carolina by Dylann Roof on 17 June, 2015 that killed nine African American parishioners, the family members of the victims also told Roof that they forgave him. Roof has never admitted any remorse for his killings.

Despite the clear religious overtones of the victim's families actions, Justin Hansford, the executive director of the Thurgood Marshall Civil Rights Center at Howard Law, contends that the culture of forgiveness that emanates from America's black community derives from the US never condoning black anger when directed towards white Americans.

"We see the black community take the moral high ground because you don't get the right to be angry with white people in America. If you're angry it is seen as unjustified," says Hansford.

Delores Qualls prays with visitors in front of the Emanuel AME Church on the one-month anniversary of the July 2015 mass shooting in Charleston, South Carolina

American culture has historically depicted slave rebellions as unwarranted acts of black aggression against white Americans, and as the black community has pursued freedom and equality there has always been a profound debate about the level of anger black America can constructively express towards white America.

Titans of the black intelligentsia have long debated various approaches for black equality and the best ways to channel and express black anger. During the civil rights struggle of the 1960s, the conflicting philosophies of Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X highlighted this tension.

Read more from Barrett

"There has always been a dichotomy between the Christian way of responding to injustice - turn the other cheek - and the black Muslims and their willingness to express anger and have a dignity with their expression of anger," says Hansford.

Many black Americans have embraced the black Muslim community and the Black Panther movement because they can provide a constructive platform for expressing black anger at the systemic racial oppression the white community has created.

Mourners gather for the funeral of Rev Clementa Pinckney, killed in a mass shooting in Charleston in 2015

When looking at the facts of the case, there are ample reasons for the black community to be angry.

On 6 September, 2018, Guyger returned home to her apartment complex after finishing work as a Dallas police officer. Guyger claims to have mistakenly parked her car on the wrong floor, and walked into Jean's apartment believing it to be her own. Upon seeing Jean on his couch eating ice cream, Guyger claims to have thought he was an intruder and, in a moment of fear, used her government issued handgun to shoot and kill Jean.

Initially, Guyger was only charged with manslaughter and kept on the police force, but following public outrage she was then charged with murder and fired.

Guyger has always contended that the killing was a tragic accident, and former Dallas police chief Craig Miller said that Guyger's killing of Jean was "justified" because Guyger suffered from a temporary condition called "inattentional blindness," which is defined as "the failure to notice a fully-visible, but unexpected object because attention was engaged on another task, event, or object."

Amber Guyger (left) said she thought Botham Jean was an intruder in her own apartment

Essentially, Miller believed that Guyger should not be charged with murder because she was not paying attention when she murdered Jean.

According to Hansford, America's cultural stifling and stigmatising of black anger has made forgiveness one of the few recourses for the black community. The alleged illegitimacy of African American anger has many American manifestations - notably the "Angry Black Woman" and "dangerous" black men - and America has long mythologized the alleged benefit of the black community forgiving white America.

Even Harriet Beecher Stowe's Uncle Tom's Cabin, published in 1852, which re-shaped American views on slavery, professed the supposed benefit of Christian love and black forgiveness as a way to overcome the cultural degradation of American slavery. Yet over 150 years later black Americans are still being unjustly murdered and terrorised, and forgiveness is still depicted as an adequate solution.

A man carries a wreath of flowers into the funeral service for Botham Jean in September, 2018

Brandt Jean's decision to forgive Guyger remains a personal decision, but Judge Kemp's decision forces America to contend with the tragic subjectivity of our justice system.

Unless Judge Kemp normally embraces, prays, and gifts a Bible to those she sends to prison, America must ask why Guyger warranted this degree of compassion and others did not. Does this undermine Kemp's impartiality?

"What is justice in this case? If you're going to bust into someone's house and shoot them dead, and then get five years in prison and a hug from the judge. Are you okay with that? And why don't similar sentences and shows of compassion happen more often?" says Hansford.

For many members of the black community, who also struggle to express their anger at America's systemic oppression, this trial represents one of many examples of how precarious and under threat black life has always been in America. Compassion might feel right in the moment, but the debate still rages as to whether it brings America closer to a semblance of racial equality.

Barrett is a writer, journalist and filmmaker focusing on race, culture and politics

More on race relations in the US

Racism in the US: Is there a single step that can bring equality?

- Published18 July 2016

- Published30 July 2015

- Published17 November 2017

- Published22 June 2015

- Published19 June 2015

- Published3 October 2019

- Published19 June 2015

- Published3 October 2019