Prohibition: US activists fight for temperance 100 years on

- Published

Though Prohibition was repealed in 1933, alcohol remains controversial in the US

It is 100 years to the day since Prohibition came into effect. The 18th Amendment to the Constitution banned anyone in the US from selling, making, importing or even transporting alcohol.

Criminal gangs immediately took over the industry. Speakeasies sprung up nationwide to sell illegal liquor and tens of millions flouted the legislation.

By 1933 it had been repealed - the only instance when a constitutional amendment has been overturned in this way.

Prohibition is now viewed as a failure. No major political parties or organisations support its return, and there is little public support for such an extreme response in the future.

But alcohol remains controversial in the US. The drinking age of 21 is higher than in other nations where drinking is legal. Dry counties and dry towns - where alcohol sales are restricted or barred outright - are dotted throughout the country. And Gallup polling from last year shows that nearly one fifth of respondents said drinking alcohol was "morally wrong", external.

A century on, a small group of Americans are fighting to keep the dream of the so-called "noble experiment" alive.

"You should think of the Prohibition Party as an exercise in living history," says Jim Hedges, treasurer to the party, which is the third-oldest in the US.

"We're trying to keep the concept alive and the history alive," he tells the BBC. "But as far as getting big enough to have influence, it's not going to happen any time soon."

The US temperance movement, which sought to control or even ban alcohol sales, developed through the 19th Century. Campaigners focused on the perceived immorality of drinking as well as the health effects. Religious groups like Methodists and later organisations like the Anti-Saloon League helped bring about the law change.

Dr Julia Guarneri, senior lecturer in US history at the University of Cambridge, tells the BBC that women's groups - in particular the Woman's Christian Temperance Union (WCTU) - were vital in bringing about prohibition.

"They thought alcohol was one way that money went from the employer to the employee to the saloon, and never reached the family," Dr Guarneri says. Women and children were also victims of abuse from alcoholic husbands and fathers.

Women's groups across the country - like the women of Madison, Minnesota - fought for prohibition

As reformers pushed for women's right to vote - ratified in the 19th Amendment, which was officially adopted just eight months after Prohibition took effect - women activists also sought to ban alcohol, seeing it as another way that women were oppressed in society.

"There's more of a connect between those two pieces of legislation than you might think," Dr Guarneri says. "The WCTU saw the banning of alcohol as a way both to keep families happier and healthier, and women happier and healthier."

Worries about the large numbers of immigrants coming to US shores at the end of the 19th and early 20th Centuries - in particular Catholics and Jews travelling from southern and eastern Europe - were another factor.

Some European Catholics in particular brought a beer-drinking culture to the US which was alien to its Protestant populations. But on top of this, both Catholics and Jews incorporate alcohol in their religious rituals. While these ceremonies were still allowed during prohibition, Dr Guarneri says that alcohol "became a way to police and oppress those immigrant populations".

The start of World War I further helped the temperance movement. Campaigners won support arguing that grains should be used for food rather than for beer during the conflict, while German immigrants or their descendants owned many of the breweries.

"So it was very easy to paint a portrait of alcohol being un-American," Dr Guarneri says. "You name it - Pabst, Schlitz, Budweiser... there wasn't going to be a lot of public sympathy for the owners of the breweries from the US."

But Prohibition was widely flouted. Many Americans, particularly the wealthy and the privileged, dodged the law with ease. President Warren Harding is said to have openly served alcohol confiscated by his government at the White House.

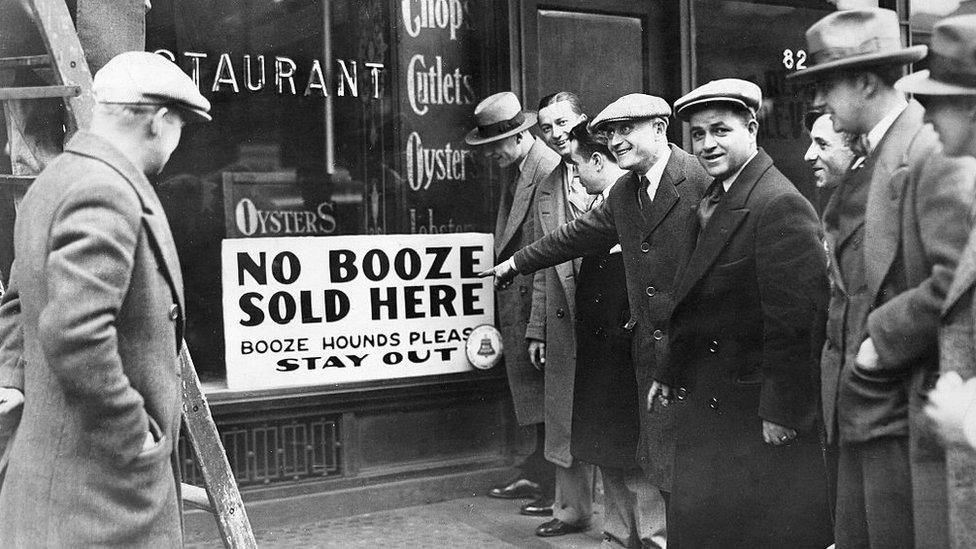

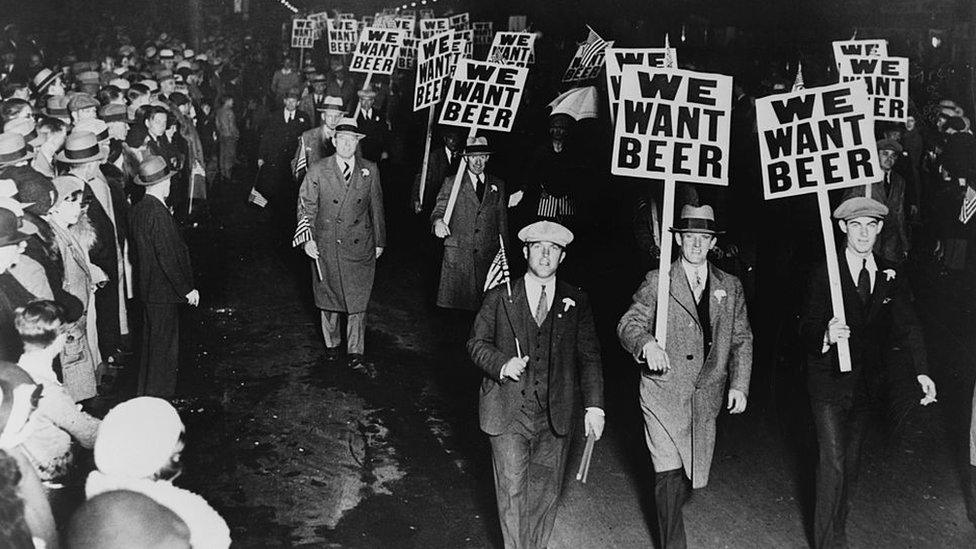

Alcohol proved to be more popular than temperance campaigners believed

The law grew more and more unpopular. Politicians also missed the tax revenue from alcohol sales after the Wall Street Crash of 1929. Franklin Roosevelt promised to repeal the measure in his bid for the presidency in 1932, and within a year of him coming to office, national prohibition was dead.

Sarah Ward, former president of the WCTU, tells the BBC that Prohibition "probably did our organisation more harm than good after the repeal".

To join the WCTU, applicants must pledge to avoid alcohol and pay membership dues. Ms Ward signed up as a teenager in the 1950s, and has kept that pledge to this day.

She spent decades teaching people about the health impact of alcohol, and says she is proud of that work. But she said the current state of the temperance movement in the US was "very discouraging".

"We can always hope that somebody will realise and a corner will be turned and that'll be great if it happens," Ms Ward says - although she thinks members of the WCTU are "more realistic" now.

"Today, as far as Prohibition is concerned, we will have that when each individual makes the choice that that is the best way for them to live," she said. "We can't get restrictions on anything. Everybody wants to be free and do their own thing."

A new exhibit looks at the highs and lows of drinking in America.

Prohibition Party treasurer Jim Hedges agrees. Mr Hedges was the party's presidential candidate in 2016 when they took just 5,600 votes nationwide - albeit far more than the 518 they won in 2012, and their best result since 1988. He says the party would like to see a "sea change" of public opinion to allow the return of national prohibition.

"If we were to try to impose that from the top down without having public support, it would be unenforceable," he says. Their plan this year is to focus on states which have easier rules for smaller parties to get on the ballot.

Phil Collins, the party's 2020 nominee, hopes they can get on the ballot in Arkansas, Colorado, Louisiana, Mississippi and Tennessee.

"Four years ago the party was on the ballot in only three states. And this time it'll be five states," he tells the BBC. "So I'm sure we'll get more votes than we did then."

Dry counties and towns, and so-called "blue laws" - restrictions on when and where you can buy alcohol, for example on a Sunday or after a certain time at night - exist across the US.

But the general trend is for more liberalisation. Massachusetts had about 20 wholly dry towns in the year 2000, but several have started to allow the sale of alcohol - albeit in restricted ways.

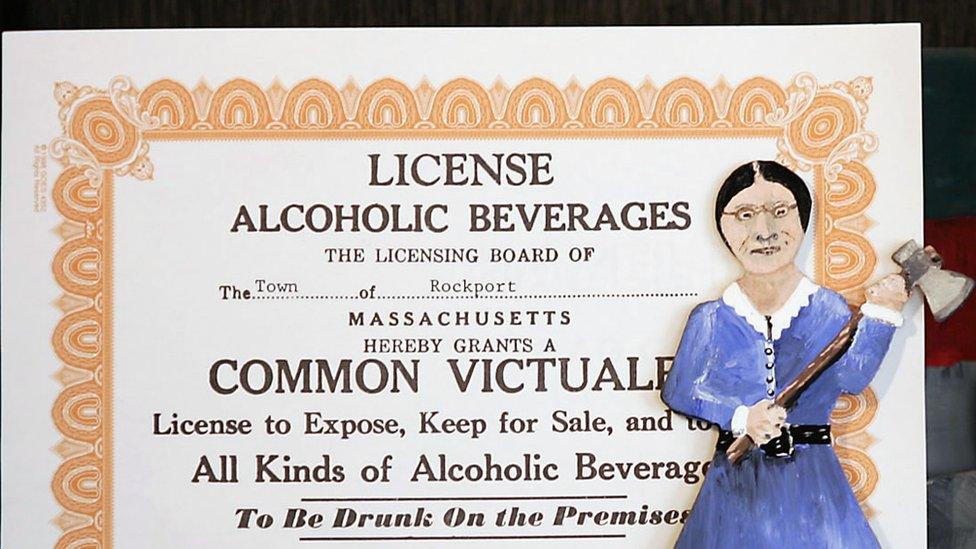

A Rockport liquor license - next to the hatchet-wielding figure of Hannah Jumper

The town of Rockport was dry from 1856, when organiser Hannah Jumper rallied women to attack liquor-serving establishments with hatchets. A referendum in 2005 finally granted restaurants the right to serve alcohol with meals, but it was only in 2019 - close to 162 years after the infamous "Hatchet Gang" raid - that the town granted its first retail licence to sell alcohol.

Jay Smith tells the BBC that after the town's only grocery store closed, the community decided to grant a licence to the first person to open a store in Rockport. His family opened the Whistlestop Market, which sells beer and wine at a mall by the train station.

Mr Smith says the town has been overwhelmingly supportive, barring "maybe one or two people [who] have let us know that they're against it." But ultimately, he says it is a matter of personal choice.

"I think Prohibition was a response to the difficulties of alcohol. Though we sell alcohol, we're for responsible use," he says. "People can have a personal or philosophical attitude against alcohol - I can't argue against that. That's their personal choice and that's what's right for them."