Bernie Sanders quits: It looked so good for him. What went wrong?

- Published

Bernie Sanders formally suspended his presidential campaign on Wednesday, acknowledging that he had no realistic path to winning the Democratic nomination.

In reality, however, the campaign's death blow came weeks earlier, in Michigan and Missouri, before the Democratic primary season entered suspended animation for weeks, with the coronavirus pandemic shuttering the campaigns and forcing states to postpone their primaries.

It was at that point that it had become painfully clear for all but the most devoted Sanders faithful that there would be no rebound for the campaign; no revival of flagging momentum. Those defeats broke the back of the campaign, with the coronavirus outbreak only temporarily delaying the final reckoning.

Reality sinks in

At Courigan's Irish Pub in St Petersburg, Florida, in early March, a few Sanders campaign workers gathered to watch the results come in from Michigan and Missouri. The significance of what they were watching played out on their faces. Their state's primary was just a week later, and if Sanders couldn't win in the Midwest, where he had done well in his 2016 presidential bid, he had little hope of prevailing in Florida, where he was trounced.

The room was spacious but mostly empty. A solitary Sanders banner hung under a television screen showing cable news coverage of the vote-tally. The mood was funereal. There wouldn't even be a Sanders speech that night to buck up the troops. A scheduled rally from Ohio was cancelled at the last minute because of the pandemic, and he had travelled back to Vermont.

As the steady drone from the television continued, Jeremy Dolan, a 27-year-old cafe owner who was volunteering for Sanders, discussed what he would tell his friends who had helped with the campaign.

The Sanders message connects strongly with young people

"Even if we do not come out victorious, you are still powerful and the ideas that you hold about many important issues are popular across the United States," he said. "We cannot give up on fighting for those issues even if it doesn't go our way here."

Earlier in the day, at a campaign canvassing event at nearby University of South Florida, some of the supporters were less philosophical - and more critical of the Democrat who was beating Sanders.

"Bernie is really the only option if we want a sustainable, progressive future," said Rachelle Wetsman, a senior at the school. "Besides the fact that Joe Biden is losing his mind, his politics stand for nothing. He wants to bring us back to the era that got Trump elected in the first place. But Trump is a symptom, not the cause of these issues."

Silver linings

Although the 2020 Sanders effort, like his first run in 2016, ended in defeat, the drawn-out, subdued conclusion shouldn't overshadow the fact that a lot went right with the Sanders campaign this time around.

Four years ago, he had a somewhat slapdash organisation, started on a shoestring budget and only ramped up once the support - and money - became a torrent. In 2020, the campaign had an unrivalled infrastructure, with a vast network of volunteers and paid staffers, and the funding to compete in every single contest.

For the 2020 campaign, Sanders brought in an astounding $181m in donations, more than half of which came in contributions smaller than $200. Joe Biden, by contrast, raised $88m, most of which came from larger donations.

A family split over Bernie Sanders - he inspired devotion but also doubts about electability

Another Sanders strength was his dedicated support of young voters - a bedrock of his campaign in 2016. Even when he lost states by large margins to Biden, Sanders carried a majority of voters under 30.

"Politicians are old people," said Wetsman. "It's our future at stake, not theirs. I think young people are fed up, and they know that we need a progressive future."

Sanders also had some success expanding his appeal, with inroads among Latinos. They were the key to the senator's victories in Nevada and California, two states he lost to Hillary Clinton in 2016.

Tio Bernie - "uncle Bernie" - became a term of endearment for many of the senator's young Latino supporters.

"Bernie's message resonates with those who are Latin voters because his story is very similar to the story of people from Latin backgrounds," said Jackie Azis, one of the volunteers at the St Petersburg watch party. "He comes from a family of immigrants that couldn't even afford basic things like curtains and rugs."

Bernie appealed to young Latino voters like Alexis and Amira.

Then there are the big-picture victories that Sanders has pointed to as the lasting legacy of his campaign. He says he won the "generational debate", citing his margins among young voters. He has also declared victory in the "ideological debate", pointing to issues like universal healthcare, aggressive steps to address climate change and free college education that have gone from fringe proposals to the mainstream of the party.

"It's common to say now that the Sanders campaign failed," political commentator and author Noam Chomsky said in an interview with Democracy Now radio programme on the day Sanders suspended his campaign. "I think that's a mistake. I think it was an extraordinary success, completely shifting the arena of debate and discussion."

The problem, Sanders conceded at his press conference the day after his Michigan loss, is that while he was shifting the party and winning the hearts of younger voters, he was "losing the debate over electability". And being "electable" - or at least being perceived as someone who could get elected - is what really mattered to Democratic voters this time around.

Warning signs

On a brisk but sunny February morning in Cedar Rapids, James Hood stood with his wife and two adult children to listen to Sanders hold a get-out-the-vote rally on the eve of the Iowa Caucuses.

The retired lawyer from Davenport said he would give the candidate a look, but he wasn't going to vote for him. He said Sanders was too old and too divisive.

"I think a lot of people in this country would find it difficult to vote for Bernie," he said. "Personally, I like him and think he would do OK. But I wonder if maybe he had some policies that were closer to the centre, they might get through, as opposed to doing away with all college costs."

Hood was the kind of voter Sanders needed to win over if he wanted 2020 to turn out differently than 2016. He said he liked Sanders that time around, too, going so far as to put a Bernie sign in his yard. He ended up voting for Hillary Clinton, however, because he thought she was the safer pick.

Four years later, Sanders hadn't changed his mind.

‘We voted for Obama, then Trump’ - Could Sanders appeal to swing voters?

Still, Sanders came very close to becoming the breakaway favourite to win the Democratic nomination. He ended up with the most votes after the extended, chaotic Iowa results were announced a week after the caucuses. In New Hampshire, he posted a narrow victory over Mayor Pete Buttigieg and the rest of the crowded field. Then he dominated Nevada, beating Biden by 26%.

That, it turned out, was the high water mark of the Sanders campaign.

"We are bringing our people together," Sanders told a cheering crowd the night of his win. "In Nevada we have just brought together a multigenerational, multiracial coalition which is not only going to win in Nevada, it's going to sweep this country."

It turned out it didn't sweep the country.

Instead, Sanders ran headlong into a resurgent Biden, who posted a surprisingly strong win in South Carolina just a week later. The former vice-president's support among older and black voters was replicated just a few days later across the south, as he claimed victory in 10 of the 14 states holding primaries on "Super Tuesday".

Sanders's front-runner status was gone.

A week later, he lost Michigan - a state that had given his 2016 campaign new life with a narrow win over Clinton. After that, massive defeats in Florida and Illinois gave Biden a lead that was all but insurmountable.

Missed opportunities

The second-guessing and what-ifs about the Sanders campaign, particularly the senator's moves during those heady moments after New Hampshire and Nevada, have already begun. Could he have made different choices, said things differently, that would resulted in a better outcome?

"There certainly was a week or two that was very exhilarating and optimistic right after Nevada," said Norman Solomon, a California Sanders delegate to the Democratic National Convention in 2016 and co-founder of the progressive advocacy group Roots Action. "I believe that South Carolina was the tipping point against Bernie."

While Sanders succeeded in expanding his coalition among some Latinos, his failure to win over black and elderly voters proved costly. Congressman James Clyburn's endorsement helped Biden win 61% of the black vote in South Carolina - and served as a springboard for the former vice-president.

Meanwhile, Sanders's losses in Michigan and Missouri suggested he was haemorrhaging support among white working-class and union voters who helped him stay competitive against Clinton in mid-west states.

After his Nevada win, the spotlight glare on Sanders became white-hot.

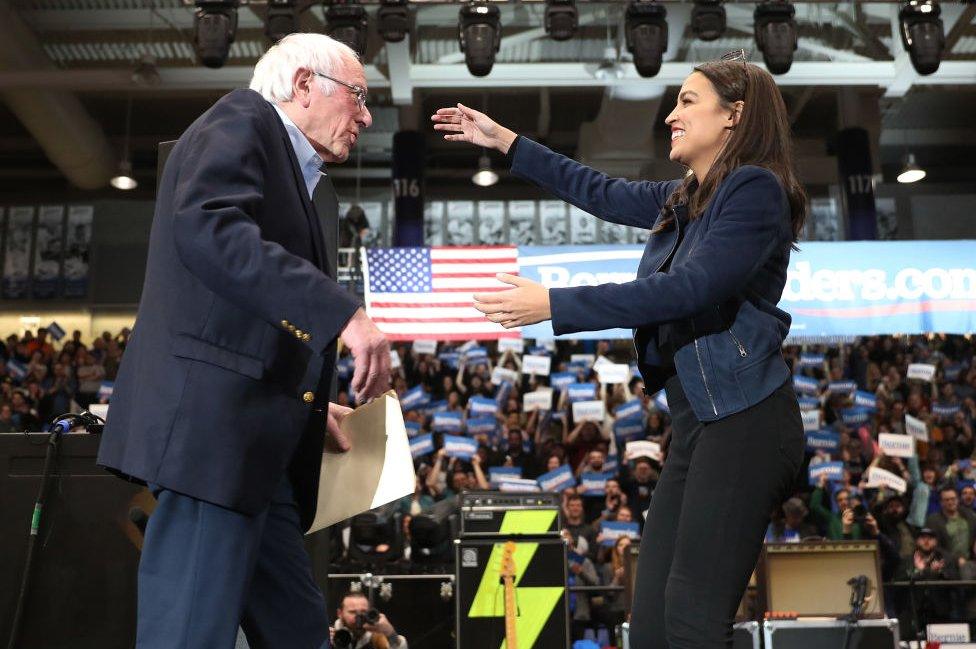

No one got bigger crowds on the campaign trail

He was pressed during a television interview to explain old comments praising Cuban dictator Fidel Castro's education policies and the communist Sandinista movement in Nicaragua. Those remarks, and his decision to stand by them, almost certainly cost him support in Florida, where Latino voters from the Caribbean and South America associate socialism - even Sanders's "Democratic socialism" - with totalitarian dictatorships.

"I feel like as soon as Bernie said something positive about Castro, that turned a lot of people off," says Maria Zamora, a University of South Florida employee who attended the Sanders event in March. "He was not praising him as an individual, but they view Castro as this person that's in control of everyone and every one's decisions."

Sanders was also accused by more centrist Democratic pundits and commentators of being an extremist. James Carville, who managed Bill Clinton's presidential campaign in 1992, called the Vermont senator an "ideological fanatic".

Sanders snapped back: "We're taking on Trump, the Republican establishment, Carville and the Democratic establishment. But at the end of the day, the grassroots movement that we are putting together of young people, of working people, of people of colour, want real change."

In a tweet on the eve of the Nevada Caucuses, external, Sanders was even more blunt.

"I've got news for the Republican establishment," he wrote. "I've got news for the Democratic establishment. They can't stop us."

Such an us-against-them framing may have played well with the Sanders base, but it also could have turned off some potential supporters and prodded his opponents within the party to band together to defeat him.

"When things start falling short, I don't think seeking out who to blame, instead of identifying how to adapt, is the smart thing to do," Congresswoman Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez - a strong Sanders supporter - told the Washington Post, external in mid-March. "I think we have to identify, 'OK, how do we bring in people?'"

The opposition

On the eve of the Super Tuesday voting, two of the more centrist candidates - Amy Klobuchar and Pete Buttigieg - dropped out and threw their support to Biden. Former Texas Congressman Beto O'Rourke, who had suspended his presidential campaign in 2019, also offered his endorsement.

A Buzzfeed article about the Sanders campaign, external recounts how one senior staffer was "visibly shaking with nerves" after news of the endorsements came out.

The emotional blow to the campaign was very real.

If Sanders had "played nice", could he have prevented the centrist consolidation and done more to make the party's establishment and more centrist voters and politicians comfortable with his campaign?

"At certain point, it is sort of his fault," said Noah Meyers, an incoming college student who attended the South Florida volunteer event in March. "He couldn't decide if he wanted to play politics or go full throttle against the establishment."

Meyers adds that it probably wouldn't have mattered, however. Sanders was going to get attacked no matter what he did.

"Bernie Sanders is used as a proxy for poor and working people in the United States," he said. "So the fact that the establishment detests Bernie Sanders is not a reflection of Bernie Sanders, it is a reflection that the establishment detests poor and working people."

This year could be Sanders' last run for the White House

Solomon also contends that animosity from the mainstream media was perhaps the greatest obstacle facing the campaign - and one that could not have been avoided. While Sanders's grass-roots fundraising machine gave him a massive financial advantage over Biden, Solomon says it was more than balanced out by the warm treatment the former vice-president received from the press.

"You can't put a monetary value on the so-called free media Biden has gotten this past year," Solomon says. "The corporate media was tremendous trouble for Bernie."

In one particularly fraught moment the day before the Nevada Caucuses, the Washington Post ran an article, external - based on unnamed sources - alleging that US intelligence officials had informed Sanders that the Russian government was surreptitiously trying to help him to disrupt the Democratic race.

Sanders suggested the Post's timing was meant to damage his campaign, sarcastically calling the paper's reporters "good friends".

Read more on Joe Biden

WHO IS HE? Third White House run for 'Middle Class Joe Biden'

THE CONTROVERSIES: Joe Biden, the touchy-feely politician

ON THE CAMPAIGN TRAIL: Watch Biden on 'No Malarkey' tour

WHERE HE STANDS: Against other Democrats like Obama

Progressive split

Another big what-if that will torment the Sanders faithful in the days ahead is whether, while the centrists united, divisions within their own ranks cost them victory.

Elizabeth Warren, the progressive senator from Massachusetts, was probably closest to Sanders ideologically among the Democratic candidates. She dropped out of the race shortly after a string of disappointing finishes on Super Tuesday, but she pointedly declined to endorse Sanders. Instead, she noted that they had much in common from a policy perspective, but some of his supporters were abusive.

Warren and Sanders had exchanged heated words after a contentious February debate in Iowa, and in the days that followed Warren was savaged on social media by Sanders loyalists, who called her a snake and a traitor. While the Sanders camp reportedly made overtures to Warren's staffers around Super Tuesday, they viewed those efforts as too little, too late.

Meanwhile, the Sanders' side sees Warren's cold shoulder as a stinging and costly betrayal.

"They had a fork in the road, and they chose to be silent and do nothing," Solomon said. "By doing nothing, it was an explicit boost to Biden, and that will always be on her record. We're never going to forget that."

Black swans

Some of the pitfalls and obstacles facing the Sanders campaign - such as the struggle to win the support of black voters, critical media coverage, the reluctance of the Democratic establishment and centrists to make peace with the senator, and the negative connotations of his self-proclaimed "Democratic socialist" identity among parts of the electorate - were predictable.

Then there were the unexpected "black swan" events that posed particular challenges to Sanders.

His heart attack in October threatened to derail the entire campaign. Donald Trump's impeachment trial in January kept Sanders tied to Washington, DC for two weeks, while other candidates - particularly Buttigieg - were able to turn repeated trips through Iowa and New Hampshire into growing support.

Finally, the coronavirus outbreak put a Sanders campaign that was already on its heels after a string of defeats into indefinite deep-freeze.

While the chances of a comeback were remote given Biden's lead in national convention delegates after his March wins, state after state delayed their primary contests into June. There was no chance of a surprise victory; no hope of a change in momentum.

And when Wisconsin, a state Sanders won comfortably in 2016, decided to move forward with its vote this week, social distancing and shelter-in-place orders ensured that Sanders was unable to hold his trademark raucous rallies or deploy his millions of door-knocking volunteers even if he wanted to.

The reality was unavoidable, and on Wednesday Sanders acknowledged it.

Sanders addresses supporters: 'I wish I had better news'

"As I see the crisis gripping the nation, I cannot in good conscience continue" he said in video broadcast from his home in Vermont. "I wish I could give you better news, but I think you know the truth and that is we are some 300 delegates behind Vice-President Joe Biden and the path toward victory is virtually impossible."

Sanders added that he would remain on the ballot in the remainder of the primaries and hoped to amass more delegates to give him the ability to influence the party's manifesto and rules at the national convention, which has been delayed to August. The active campaign, however, was done.

The road ahead

In his Wednesday concession speech Sanders also struck a hopeful note, saying that although his campaign was coming to an end, the movement he created was not.

"While the path may be slower now, we will change this nation, and with like-minded friends around the globe, change the entire world," he said.

In just five years Sanders created a movement essentially out of thin air. When he kicked off his first presidential bid in April 2015, external, it was with a sparsely attended press conference on the grounds of the U.S. Capitol. There was little indication at the time of the grass-roots and fundraising juggernaut that would follow.

The politician who had spent decades as back-bencher in Congress transformed himself into the leader of a popular, grass-roots force that electrified supporters and sent traditional party power-brokers scrambling. He became, arguably, the most influential force on the party in recent memory - at the very least on a short list with Barack Obama, Nancy Pelosi and Bill Clinton. And his power came not from the office he held, but from the people he spoke to - and for.

Now the 78-year-old senator is approaching the twilight of his political career, and it seems unlikely he will again try to head the Democratic national ticket. The question, then, becomes who will lead of the movement going forward.

Warren is an obvious choice - if the acrimony of the recent campaign eventually settles. New York Congresswoman Ocasio-Cortez is the rising star in the progressive ranks. Her endorsement of the senator shortly after his heart attack is credited with reviving what was at the time a flagging campaign.

A passing of the torch?

Other Sanders advocates - Congressman Ro Khanna of California and Congresswoman Pramila Jayapal of Washington are also seen as young, charismatic figures.

"Bernie is very beloved, and he's going to continue in the Senate and as a public person for many years to come," Solomon said. "But the leadership is going to diversify."

He added that outside of elected officials, the ranks of progressive activists continues to grow, and the movement is creating its own media outlets to counter with what he says is the unfair coverage of the mainstream press.

The bottom line, he concludes, is that Sanders has opened a door for the next generation of liberal grass-roots candidates - ones who might finally win a White House prize that seemed, for at least a few weeks this year, tantalisingly within his reach.

"The Democratic Party establishment still retains a lot of power," Solomon said. "Yet in contrast with four years ago, there's now an understanding from the hierarchy that they can't just tell progressives to go jump in a lake. If they do that, people like Trump win."

- Published3 February 2020

- Published5 March 2020

- Published19 May 2020

- Published9 December 2019

- Published2 March 2020

- Published17 January 2020

- Published4 February 2020