George Floyd: The personal cost of filming police brutality

- Published

Filming police conduct on mobile phones has become commonplace in the US

When videos of controversial police encounters generate headlines, there's an important figure in the story that we rarely hear about - the person filming.

By the time 17-year-old Darnella Frazier started recording, George Floyd was already gasping for air, begging, repeatedly, "please, please, please".

The camera had been rolling for 20 seconds when Mr Floyd, 46, uttered three more words that have now become a rallying cry for protesters.

"I can't breathe," Mr Floyd said.

The words were slightly muffled. He strained to speak as he lay face down in handcuffs, pinned to the floor by three police officers. One of those officers, 44-year-old Derek Chauvin, pressed a knee against Mr Floyd's neck.

Ms Frazier was taking her nine-year-old cousin to Cup Foods, a shop near her home in Minneapolis, Minnesota, when she saw Mr Floyd grappling with police. She stopped, pulled out her phone and pressed record.

For 10 minutes and nine seconds she filmed until the officers and Mr Floyd left the scene; the former on foot, the latter on a stretcher.

Derek Chauvin has been charged with second-degree murder over the death of George Floyd

At that point, Ms Frazier could never have imagined the chain of events that her video would set in motion. At the click of a button, the teen spurred wave after wave of protests, not only in the US but across the world.

"She felt she had to document it," Ms Frazier's lawyer Seth Cobin told the BBC. "It's like the civil rights movement was reborn in a whole new way, because of that video."

Ms Frazier, a high school junior, was not available for interview. Her lawyer said she was traumatised by what she saw outside Cup Foods on 25 May. It was "the most awful thing she's ever seen".

The street outside Cup Foods has become a memorial for George Floyd

Since then, she has seen a therapist and "is doing pretty well", Mr Cobin said.

Coping with the response to her video has not been easy either. On Facebook, where she posted the video, external, the reaction was a mix of shock, outrage, praise and criticism.

In a Facebook post, shared on 27 May, Ms Frazier responded to suggestions she filmed the video for "clout" and did not do enough to prevent the death of Mr Floyd.

"If it wasn't for me, four cops would've still had their jobs, causing other problems. My video went worldwide for everyone to see and know," Ms Frazier wrote.

The backlash to Ms Frazier's video epitomises the dilemma facing bystanders who capture high-profile incidents of police violence on camera. Other similar cases have shown it to be an unenviable position to be in.

When emotions run high, videos of police brutality can have a polarising quality, dividing opinion across racial and political lines. Standing at the centre of that debate can take a heavy toll.

More on George Floyd's death

WATCH: What next for US protesters?

SOLUTIONS: Seven ways to reform police

CRIME AND JUSTICE: How are African Americans treated?

VIEWPOINT: Tipping point for racially divided nation

As a veteran cop watcher in New York, Dennis Flores knows a thing or two about the pitfalls of filming police activity.

He has been arrested more than 70 times since he started documenting the city's police force, the NYPD, in the late 1990s. His use of video to expose police brutality has blazed a trail for the growing police accountability movement seen across the US today.

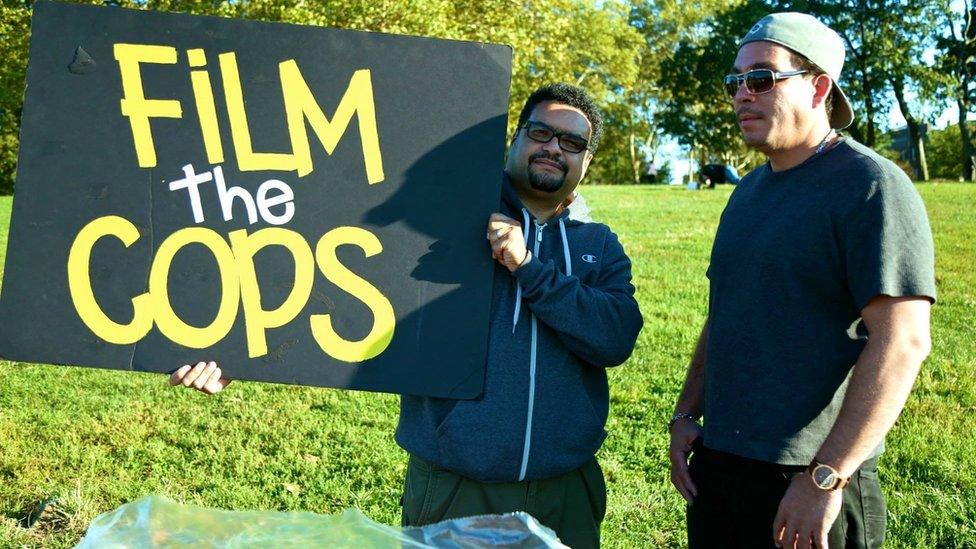

Dennis Flores (L) has been filming police since the 1990s

The movement's roots can be traced back to 1991, when a plumber filmed what has been described as the world's first viral video of police brutality, external. It showed the savage beating of Rodney King, an unarmed black man, by several police officers after a car chase in Los Angeles, California.

Unbeknown to the officers, George Holliday shot the footage on his then high-end Sony Handycam from the balcony of his apartment. After sharing the tape with a local TV station, the beating became a national and global outrage. That anger turned into deadly race riots a year later, when the four white officers tried over Mr King's assault were found not guilty.

"The Rodney King beating was the catalyst of video documentation," Mr Flores told the BBC.

George Holliday caught the beating of Rodney King on camera from his flat's balcony

The first amendment of the US constitution protects the right of Americans to film police.

In the early days of police observation, there were no smartphones, no social media platforms, no 5G-internet providers. It was just Mr Flores, a clunky 35mm SLR camera and a tape recorder. But as technology improved, the ability to keep tabs on police was democratised.

"Everyday individuals could suddenly expose police behaviour. And that's only escalated with cases like Eric Garner," Mr Flores said.

Mr Flores has been arrested more than 70 times while filming NYPD police officers

Mr Garner, a 43-year-old African American, died in 2014 after being placed in a chokehold by a police officer in New York. He was detained for allegedly selling loose cigarettes.

Like Mr Floyd, Mr Garner repeatedly told the officers, "I can't breathe" - words that became a rallying cry for Black Lives Matter protesters six years ago and again in the wake of Mr Floyd's death.

Mr Garner's death was ruled a homicide but, controversially, no charges were brought against Daniel Pantaleo, the officer who restrained him.

What happened to Ramsey Orta, the person who filmed Mr Garner's death, was equally controversial.

Footage of the arrest sparked national outrage - Nick Bryant reports

He alleged a campaign of police harassment after the video went viral.

Orta did not have a clean record by any means. He has acknowledged that but, in 2019, he told the Verge "the cops had been following me every day since Eric died", external.

In 2016, Orta pleaded guilty to gun and drug charges and was sentenced to four years in jail. The charges were not related to his filming of Mr Garner's death. But Mr Flores, a friend of Orta, believes his video put him in the crosshairs of the NYPD.

"The case of Ramsey Orta is a prime example of how you become a target when you film the police and decide to go public. He's been made to suffer for filming cops," Mr Flores said.

Orta has expressed regret for "not minding my business". Yet conversely, the consequences of not sharing evidence of deadly police force can weigh heavily on the conscience, as Feidin Santana discovered in 2015.

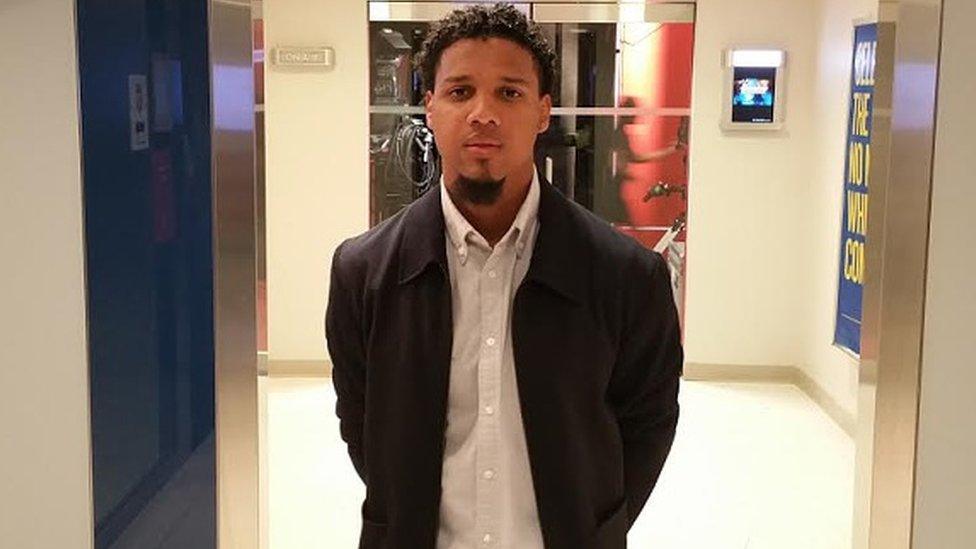

Ramsey Orta claims he was targeted by police after filming the death of his friend Eric Garner

Mr Santana was casually walking to work in Charleston, South Carolina when he came across a peculiar sight: an altercation between Michael Slager, a white police officer, and Walter Scott, an unarmed black man.

Mr Santana reached for his phone and began filming as the struggle ensued. Eventually, Mr Scott turned his back to the officer and fled. The officer paused, drew his gun and aimed it at Mr Scott's back.

Eight shots rang out and Mr Scott tumbled to the floor.

What Mr Santana had witnessed was incomprehensible to him.

"It was impossible for me to believe that a man running from an officer - without harming him - can lead to such a tragedy," he told the BBC.

The dash cam footage shows Walter Scott's car being pulled over and Officer Michael Slager asking for his paperwork before Mr Scott runs away

For three days, Mr Santana, a barber who immigrated to the US from the Dominican Republic, kept the video to himself. Fearing police retribution, Mr Santana considered erasing the footage and leaving Charleston for good. In the end, a police report about the incident changed his mind.

In the report, Slager said he feared for his life after Mr Scott took his Taser. But the video showed Slager's account to be false.

As the only person who could prove that, Mr Santana felt compelled to share the video with Mr Scott's family. Once the video was public, Mr Santana's "normal life" was over.

"I never thought the video would go viral so quickly. Death threats and racist messages were something that were hard for me. Then you understand that, in order to change things, you need to confront fear to overcome it," Mr Santana said.

Feidin Santana said he thought about deleting the footage of Walter Scott's shooting

Ultimately, it was Mr Santana's footage that led to Slager being charged with murder. To that end, Mr Santana has no regrets whatsoever.

"Silence equals complicity. I chose my side and I will continue fighting for a better society, fearless of any consequence," he said.

Technology has had a role in bringing that better society about. In the hands of ordinary people, cameras have been used to hold police to account, ensuring justice where there might otherwise have been none. In some court cases, video evidence can be the difference between conviction and acquittal.

Prosecutors will be aware of this when Mr Chauvin, the officer accused of murdering Mr Floyd, stands trial.

Investigators have extracted the video from Ms Frazier's phone for evidential purposes, her lawyer Mr Cobin said. At trial, Ms Frazier may be called upon to testify.

She has already provided a witness statement to the FBI's Civil Rights Division and the Minnesota Bureau of Criminal Apprehension (MBCA). Her statement, Mr Cobin said, was difficult to watch.

"It was very emotional. She was in tears. She went through an awful lot of trauma. She talked about how every time she closes her eyes, this is what she sees. She sees George Floyd's face as he's dying. She opens them up and he's gone, she closes them and she sees him again."

The killing of Mr Floyd has spurred protests across the world

Ms Frazier did not wish to be embroiled in a murder trial. Nor was she seeking attention by posting the video of Mr Floyd's death on social media.

In that respect, Mr Cobin compared Ms Frazier to Rosa Parks, the African-American woman who, in 1955, famously refused to give up her bus seat to a white man in Alabama.

"Like Rosa Parks, she didn't set out to be a hero or a civil rights icon. She just happened to be in a place, at the right time. This isn't a Martin Luther King, this isn't a Malcolm X, who chose to lead people. This is someone who is a regular person who did the right thing," Mr Cobin said.

- Published3 June 2020

- Published22 April 2021

- Published21 April 2021