Ervin Staub: A Holocaust survivor’s mission to train ‘heroic bystanders’

- Published

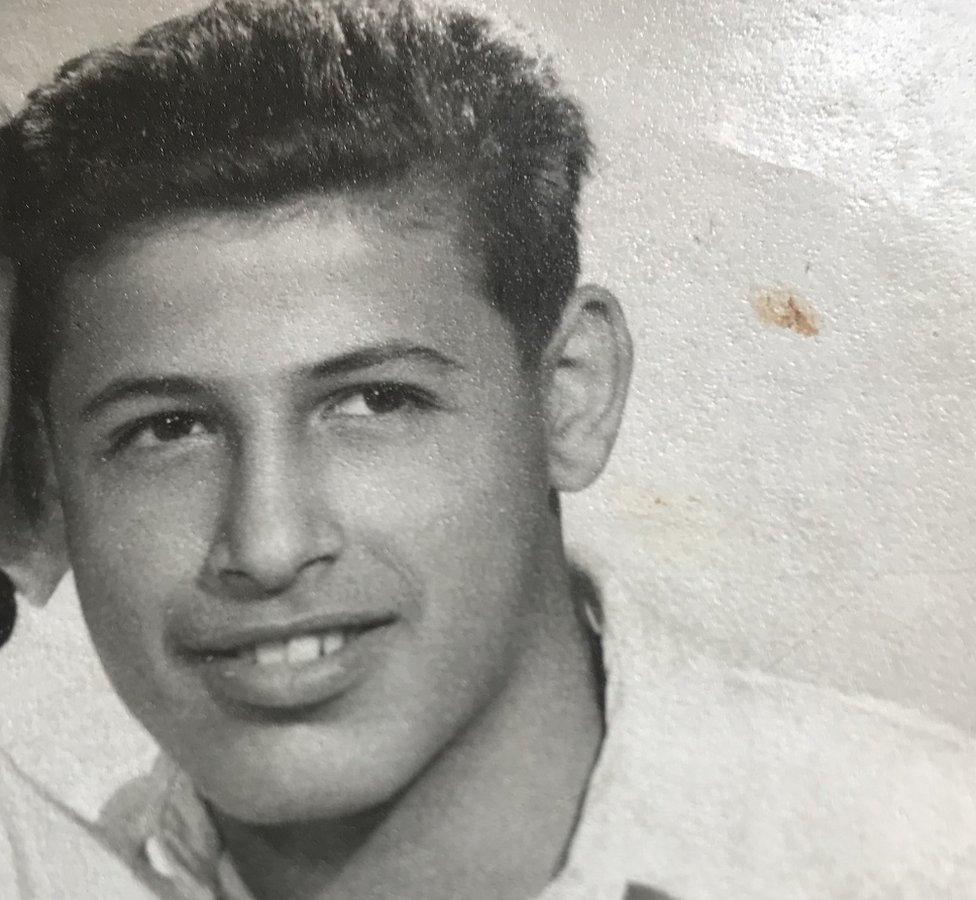

Dr Ervin Staub has been studying the psychology of violence for decades

A training programme designed to discourage police misconduct is being adopted across the US after months of protests over the use of excessive force. The Holocaust survivor behind the training believes that, after initial success in one city, it can change police culture nationwide.

As World War Two reached its crescendo, the actions of two people left an indelible mark on Dr Ervin Staub's life.

Born in Hungary to a Jewish family, he was a six-year-old child when Nazi German forces occupied Hungary in 1944. At the behest of the Nazis, hundreds of thousands of Hungarian Jews were rounded up and deported to extermination camps.

Two decisive interventions ensured Dr Staub and his family did not meet the same fate.

A woman named Maria Gogan hid him and his one-year-old sister with a Christian family.

"She looked after us kids," Dr Staub told the BBC. "I was walking with her and my sister in Budapest when the German tanks rolled in."

For a while, Dr Staub and his sister posed as Ms Gogan's relatives from the countryside. Then, when Dr Staub's mother obtained protective identity papers for his family from Swedish diplomat Raoul Wallenberg, they moved into a safe house nearby.

Advancing Soviet forces were able to drive the Germans out of Hungary by 1945

To Dr Staub, Ms Gogan was a second mother. She continued to live with the family at the safe house, risking her life to bring them food and pass another letter of protection to Dr Staub's father through the barbed wire of a forced-labour camp.

One time, as Ms Gogan returned home, she was held up at knifepoint by Hungarian Nazis. They threatened to kill her for helping Jews.

"A man who knew her came in and said, 'let her go, she's a good person'. So they let her go," Dr Staub said.

Thanks to these acts of kindness, Dr Staub and his family lived to see the end of Nazi tyranny in Hungary.

Eva Behar was taken to a Nazi death camp in 1944. What can we learn from her experiences?

After enduring the war, and a decade of communism in Hungary, Dr Staub fled via Vienna to the US, where he studied the psychology of violence, genocide and morality. He did a PhD on the topic at Stanford University and taught at Harvard University, before applying his theories on harm prevention to experiments and field research.

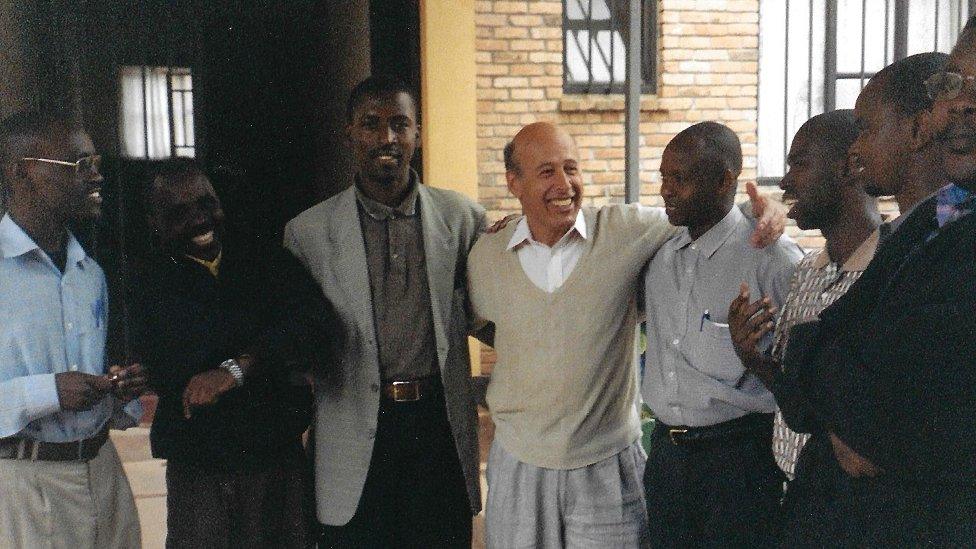

For a project in Rwanda, for example, he tried to promote reconciliation after the country's genocide of 1994. Fittingly enough, his most recent book was titled "The Roots of Goodness and Resistance to Evil".

Nowadays, it's not genocide that worries Dr Staub. It's the excessive use of force by police officers in the US.

Dr Staub fled via Vienna to the US, where he studied the psychology of violence

To quell this violence, Dr Staub had a simple idea, one that hinges on the role of active bystanders like Ms Gogan and the diplomat who saved his life.

"These people were heroic active bystanders who put themselves into great danger," Dr Staub said. "They had a huge influence on my motivation to study what leads people to help others."

At 82, Dr Staub is enjoying a renaissance of his school of thought. His active-bystander concept has started to gain traction in 2020, a year of reckoning for police forces in the US.

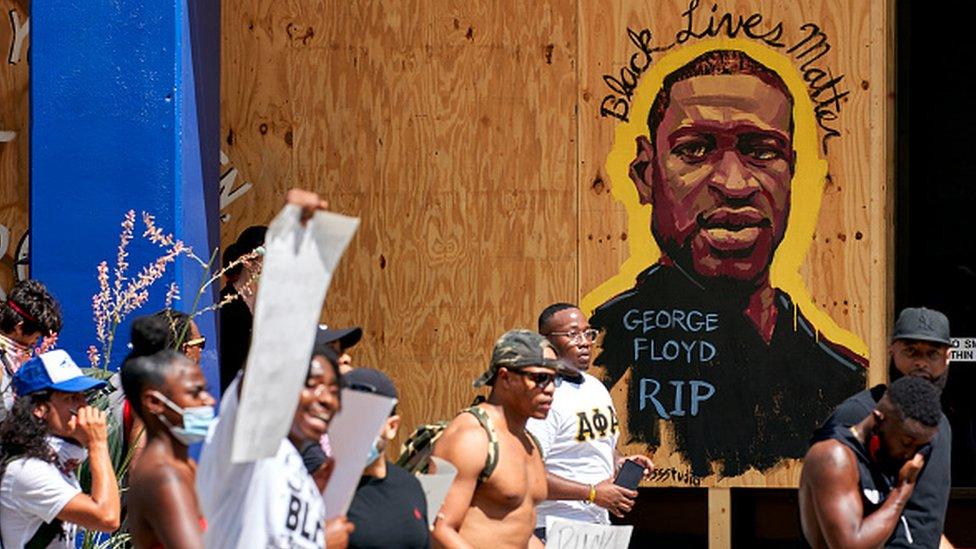

The case of George Floyd, a black man who died in custody in Minneapolis, Minnesota in May, reignited a long-running debate about racial injustice and policing in the US.

Widespread calls for police reform have sprung from the killing of Mr Floyd, and that of other black Americans.

At more than 30 police departments across the US, a training programme based on Dr Staub's ideas has been included in that push for reform.

More on policing and protests in the US:

The BBC's Clive Myrie explains why the history of racial inequality has paved the way for modern day police brutality

PERSPECTIVE: The personal cost of filming police brutality

SOLUTIONS: Seven ways to reform police

CRIME AND JUSTICE: How are African Americans treated?

Dr Staub has long stepped back from teaching at the University of Massachusetts, where he founded a PhD course on the psychology of violence. He was thinking about retiring for good this year, but demand for this training has thrust him back into the fray of the police-reform movement in the middle of a pandemic.

With a youthful inquisitiveness that belies his age, Dr Staub has acquainted himself with the trappings of 2020, from video conferences on Zoom to the demands of Black Lives Matter protests. Times have changed yet for Dr Staub, the principles of ethical policing training finally appear to be coming of age.

"Some people want to defund police departments," Dr Staub said. "We do need police, but we also need a transformation in police departments."

Dr Staub has worked on reconciliation and education projects in Rwanda

The training, called Ethical Policing Is Courageous (EPIC), external, encourages officers to intervene if they see misconduct within their ranks. It was first introduced by the police force in the Louisiana city of New Orleans in 2014.

Crucially, it emphasises the responsibility, not of the perpetrator, but of bystanders. Every officer is reminded of their duty to act if they see bad behaviour, repudiating the so-called blue wall of silence. This ethos upends the way officers traditionally think about loyalty to their partners.

"Loyalty isn't saying, 'well, you've done something wrong, I'm going to protect you'," Lisa Kurtz, an innovation manager at the New Orleans Police Department (NOPD), told the BBC. "Loyalty is me saying, 'you're about to do something wrong, and I'm going to stop you'."

EPIC training encourages officers to intervene if they think a colleague is behaving badly

Ernest Luster, a veteran NOPD officer, said the training has completely changed the dynamic of policing in the city.

"There was always this perception with police of us versus them, of them against us," says Mr Luster, a sergeant with more than 20 years' experience. "Now we're working together to make the community safe."

Mr Luster usually starts his shift with a team briefing. He reminds his colleagues to protect the community, from criminals and each other. On the beat, officers can wear EPIC pins on their lapels to signal they consent to intervention.

Ultimately, the sergeant wants the public to see officers as heroes, not villains. To that end, he likens an active bystander to Superman, "one of my biggest heroes of all time".

Knowing how, and when, to step in is a lesson that every member of the force is taught in EPIC training. And no one, not even the sergeant himself, is exempt from that lesson.

"You can have 50 years on the job, but you're still a human being," he said. "You're still vulnerable to certain people pushing a button."

Even Mr Luster, an EPIC trainer, can recall an incident when he struggled to keep his emotions in check. He almost hit a handcuffed man who had resisted arrest for trespassing.

"At that moment, a rookie cop walks over to me. He puts his hands on my chest, and immediately I thought about EPIC. Just like that. And I walked away. Now, had he not done that, I could have lost my job for excessive force."

Sergeant Ernest Luster said even he has needed his partner to intervene

Mr Luster's testimony certainly chimes with recent data on police conduct in New Orleans. The EPIC programme, alongside other reforms, appear to have yielded results.

A 2019 report by an independent police monitor, external noted a sharp drop in "critical incidents" involving the use of force by officers in New Orleans. These incidents fell from 22 in 2012, to five in 2018. That year, the NOPD did not shoot at, critically injure or kill any civilians, the report said.

Satisfaction with police has increased, too. A 2019 survey, external found that 54% of New Orleans residents were satisfied with the NOPD's overall performance, a rise of 21% since 2009.

These improved results signal just how far the NOPD has come since the dark days of the 2000s. Back then, the force was engulfed by scandal. Criminality and misconduct were rife.

"If you take almost every major federal felony that we have in law, except for possibly treason, we've had a New Orleans police officer who has been arrested, convicted, prosecuted and sued for those acts," Mary Howell, a New Orleans-based civil rights lawyer, told the BBC.

Mary Howell has seen crime ebb and flow in New Orleans over the years

Ms Howell has devoted much of her 40-year career to pursuing justice for the victims of these acts.

One of the most troubling incidents, she recalled, happened in the wake of Hurricane Katrina in 2005. That year, New Orleans officers shot six people on the city's Danziger Bridge, killing two. All of the victims were African Americans. None were armed, nor had they committed any crimes. Eleven officers ultimately pleaded guilty to charges related to the shootings, and an attempt to cover them up.

Ms Howell said she was dismayed by this and other similar incidents, which happened time and again in New Orleans. The violence, she said, came in cycles.

"You see the same patterns with domestic violence," Ms Howell said. "There would be a terrible incident, and then there would be the candy, and the flowers, and 'I am so sorry'. Then it would happen again."

At its nadir in 2012, the NOPD was brought under federal supervision, external. Known as a consent decree, the supervision order required the force to undertake sweeping reforms. The use of force, stops, searches, seizures and arrests; everything was revised to rebuild trust and improve public safety. A new training regime was a key component of that change.

That training was where Ms Howell and Dr Staub came in. Ms Howell first stumbled across Dr Staub's work in the 1990s. The lawyer read a New York Times article in which Dr Staub talked about a training programme he had designed for police forces in California, external.

The training programme was commissioned after the beating of Rodney King by Los Angeles police officers in 1991. Dr Staub said he saw "no sign of this training", despite assurances it would be implemented.

The Rodney King beating triggered race riots, marking one of the darkest periods of police-community relations in Los Angeles

Nevertheless, Ms Howell was convinced Dr Staub was on to something. For his theories on harm prevention, Dr Staub was seen as a cult figure in police-reform circles.

Years later, sensing an opportunity to spur change in New Orleans, Ms Howell revisited Dr Staub's concept of ethical policing. Maybe this could work in the city, she thought.

At Ms Howell's suggestion, the NOPD developed a peer-intervention training programme. EPIC was the outcome.

When the consent decree came into effect in New Orleans, Jonathan Aronie was one of the lawyers appointed to monitor its progress. He was impressed by EPIC, mainly because it was aimed at all officers, not just a "small number of wrongdoers".

"This was a programme for the high percentage of people in the world, and in the police department, that want to do the right thing," Mr Aronie said. "They would want to prevent harm, if they only had a skill to do it."

A new national initiative, launched after Mr Floyd's death, seeks to give officers that skill.

Officers who complete EPIC training can choose to wear an EPIC pin on their lapel

The Active Bystandership for Law Enforcement (ABLE), external project will offer support to police departments across the country in developing their own peer-intervention training programmes. Built on the principles of EPIC, ABLE training, technical assistance and research will be provided, free of charge.

An initial $400,000 (£307,000) has been raised to fund the project, led by Georgetown University and law firm Sheppard Mullin. With demand for police reform growing, ABLE organisers are hoping more funding will follow.

"After the George Floyd killing we probably received 100 calls from police departments wanting EPIC training," said Mr Aronie, chair of ABLE's board of advisers.

By October, 34 police departments in Boston, Denver, Philadelphia and other cities will have undertaken a "training of trainers" for the ABLE programme. To qualify for the training, each agency had to commit to ABLE's standards and submit letters of support from prominent community organisations.

On its own, this training does not represent a panacea for police misbehaviour, Mr Aronie said. It needs to be part of a broader cultural transformation in policing that goes beyond "pimping the programme for publicity", he said.

Still, Dr Staub's ideas are becoming the foundation of that transformation.

Protests over the death of George Floyd and other black Americans have swept the US this year

EPIC "could have changed the whole dynamic" of Mr Floyd's fatal arrest, Dr Staub said. Had they received the training, the three officers who watched on "would have felt empowered" to intervene.

They, just like Ms Gogan and the diplomat who took risks for Dr Staub, could have stepped in to challenge the actions of one, with the combined will of three.

"Individuals can make a huge difference," Dr Staub said. "They have great power, and when they join together, they have substantial power."

BBC World Service radio talked to Dr Staub about his role in transforming policing in the US for its latest episode of People Fixing the World.

You can listen to the podcast on BBC Sounds from 6 October.

- Published17 June 2020

- Published26 June 2020

- Published7 September 2020