The Californian district attorney with a unique background

- Published

San Francisco District Attorney, Chesa Boudin

San Francisco's top prosecutor has a unique life story and a background as a criminal justice reformer. He spoke with the BBC's James Clayton.

Chesa Boudin was elected district attorney of San Francisco in November last year.

His background is unusual to say the least.

In 1981, as a one-year-old, he was left with a babysitter while his parents went off to take part in an armed robbery.

They were part of the left-wing guerrilla movement the "Weather Underground".

They never came back. The robbery went wrong and a security guard and two police officers were killed.

Although his parents were the getaway drivers, and didn't pull the trigger, they were both given life sentences - though his mother was released in 2003.

He is now part of a movement of liberal district attorneys in cities like Los Angeles, Boston and Philadelphia that are trying to reform what they say is a broken criminal justice system.

They want to end mass incarceration, focus more police resources on addiction and mental health services, and decriminalise some lower level, non-violent crimes.

To his opponents, Boudin is a dangerous radical, undermining the police, and making the streets more dangerous.

The interview has been edited for clarity and brevity.

First of all, your background is quite unusual. What happened with your parents?

My parents dropped me off with a babysitter and they participated in an armed robbery. They were unarmed drivers of a switch car. But other participants in the robbery were heavily armed. And the robbery went terribly wrong, tragically so, resulting in the murder of three men - a security guard and two police officers.

They didn't come back. Instead my mother ended up spending 22 years in prison. And my father is still incarcerated today. He's serving a minimum 75 year sentence, and he may never get out.

How old were you at the time?

I was 14 months old, and I don't remember that day. I don't remember being adopted into a new family. My earliest memories are going through metal detectors and steel gates, just to visit my parents, just to be able to touch them and give them a hug.

Your mum and dad were convicted of almost exactly the same crime. Yet your mum was given a far reduced sentence from your dad. How has that affected the way that you see criminal justice?

That's right. My parents did the same thing, their role in the crime was virtually identical. But they ended up with very, very different sentences and outcomes. It's an example of one of the many ways in which the criminal justice system is horribly arbitrary and punitive.

A young Chesa Boudin visiting his mother, Kathy Boudin, in prison

My father's 75 year minimum sentence is not based on any greater culpability for his role in the crime. It's based instead on the fact that he chose to represent himself and his case went to trial.

Is that what inspired you to go down the route that you've gone down?

I've seen first hand my entire life, the failings of America's approach to criminal justice. I've seen it fail to rehabilitate or support crime victims. I've seen the way it tears families apart and horrific racial biases and economic and social costs.

Talk me through some of your policies. Why did you want to get rid of cash bail?

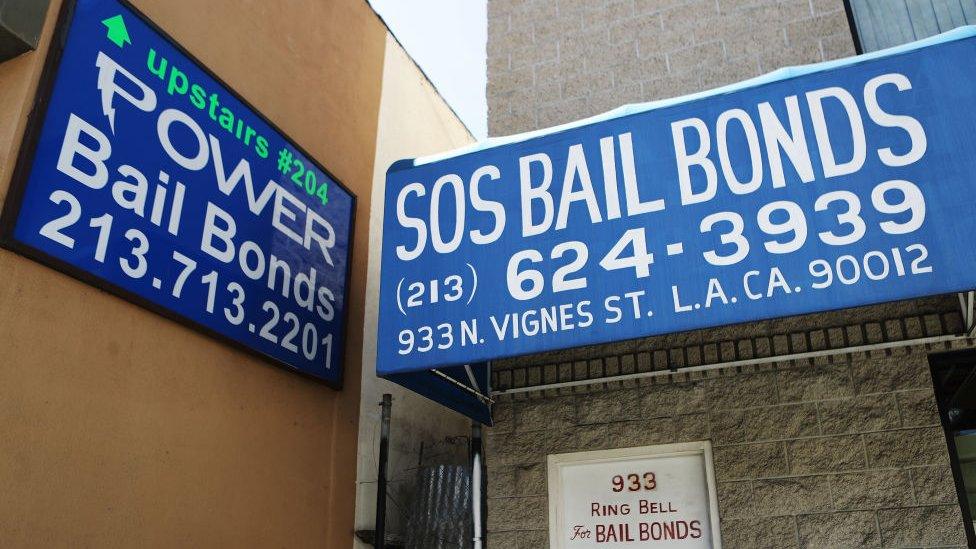

For folks who aren't familiar with the American approach to cash bail, let me just explain briefly how it works. It's one of only two countries in the world with a for-profit bail bond industry. When someone is arrested, they can immediately buy their way out. They can pay a non-refundable, usually 10% deposit and within hours, they're free. And that has nothing to do with risk has everything to do with wealth.

So for example, a really wealthy person charged with a domestic violence attempted murder, under the bail system, can buy their way out as soon as they're arrested - and go complete the murder. But a poor person arrested for shoplifting food, a low-level misdemeanour crime - a person who presents no public safety risk of violence - may languish behind bars for months simply because of their poverty.

Is there any non-violent crime you think deserves a custodial sentence?

In general? No. There are certainly exceptions though and each case is different. Jail and prison should be a last resort. And in the United States, sadly, it's become a primary response to a wide array of social problems. We need to move away from our dependence on narrow, myopic focus on punishment and putting people in cages and start focusing resources and technology and energy on attacking the root causes of crime.

In San Francisco, for example, 75% of people booked into the county jail are drug addicted, mentally ill, or both. Until we start getting at those root causes - homelessness, mental health, trauma - we're never going to decrease crime and build the safe communities that we all deserve.

You stood on a platform of not cooperating with ICE, the Immigration and Customs Enforcement authority, is that right? Have you not been cooperating with ICE?

That's right. In order for us to keep our community safe here in San Francisco, it's essential that the immigrants living here and their families, people from all over the world speaking different languages, feel safe calling the police, reporting when they've been a victim of crime, coming to court to testify, to help us solve crimes.

Protesters march outside US Immigration and Customs Enforcement offices in San Francisco

If immigrant communities fear my office, or think local law enforcement will cooperate with immigration officials, they will not come forward, they will not cooperate - and they will themselves and all of us be more vulnerable for crime.

Obviously, we're in a pandemic so it's actually quite difficult to ascertain how successful you've been. But can you point to anything that suggests your new strategy is working?

Well big picture, absolutely.

Since I took office, we've reduced the number of people in state prison from San Francisco by about a third. And we've also reduced the number of people in our local county jail from peak to trough by about 40-45%. Meanwhile, crime rates in San Francisco have plummeted by historic margins we've seen in 2020, compared to the same time period of the first 12 months of 2019. We've seen it dropping crime of nearly 25%. It's a historic, unprecedented drop.

Now I understand of course, that much of that is driven by changes in tourism and consumer habits around Covid-19. But the fear mongers, the naysayers, the police unions would have you believe that if we let people out of jail, crime will go up. And instead in San Francisco this year, we've seen exactly the opposite. Crime rates are falling as we safely decarcerate

You mentioned the police unions. The San Francisco Police Officers Association doesn't like you much, it's fair to say. They think that you undermine the police. What do you say to that?

I'm sorry they have such a narrow view of public safety. It's really frustrating that the police are more interested in promoting fear than in promoting safety in some places in this country,

Cash bail has been abolished in California

I have a great relationship with the chief of police, individual officers and captains. And we all know that to build safety, we have to work together. But San Francisco's police officer union, like so many law enforcement unions around the country, has become really disconnected from the values and needs of local communities. They spend more time and energy attacking and undermining the will of the people than they do trying to build collaborations and be creative in their approach to problem solving.

What about the criticism that you're focusing too much on the criminal here and not enough on the victim?

Well it ignores the tremendous amount of work that my Victim Services team has done this year and in general to put victims first to give victims a voice.

We're in the process of launching, for example, the most ambitious restorative justice programme in the country that gives every single victim of every single crime the choice about how they want their case to proceed - a victim-centred process that puts their needs first, or do they prefer a punitive approach that focuses on the defendant, the person who caused harm.

What would you say to people who say this - that you're using San Francisco as an experiment, a petri dish for some pretty left wing policies on criminal justice?

It's quite the contrary. We're actually using empirical evidence and meticulous data gathering to promote public safety. That's not a standard that anyone has ever held the so called 'tough on drug' policies to. You show me one iota of data that indicates that jailing people with drug addiction is an effective response. You show me one iota of data that suggests that the death penalty is an effective deterrent to violent crime. It doesn't exist.

James Clayton is the BBC's North America technology reporter based in San Francisco. Follow him on Twitter @jamesclayton5, external.

Related topics

- Published25 February 2020

- Published17 June 2020