Derek Chauvin trial: Why role of TV cameras could come into focus

- Published

The live coverage of Derek Chauvin's trial is a historic first for the state of Minnesota

From Monday, three discreet TV cameras will offer anyone with an internet connection a front-row seat to a criminal trial of global interest.

One of those cameras will be trained on Derek Chauvin, the former policeman accused of killing George Floyd in custody.

Mr Chauvin could be jailed for decades over the 25 May, 2020 death of Mr Floyd, an unarmed black man.

The knee Mr Chauvin placed on Mr Floyd's neck was filmed for all to see.

Angered by what they saw, protesters worldwide said it was time to end racial injustice. Now cameras will let them see the justice system in real-time.

Never before has a judge allowed cameras to film a full criminal trial in the state of Minnesota.

Mr Chauvin is accused of unintentional murder and manslaughter in the death of Mr Floyd

This access was granted to Court TV, a US network best known for its slick yet lurid coverage of criminal cases in the 1990s. Its "gavel-to-gavel" footage will be shared with media outlets and broadcast live to audiences globally.

Every move Mr Chauvin makes, down to the faintest facial expression, will be open to public scrutiny. During the jury selection, which was also filmed live, a suited Mr Chauvin was seen day after day, listening intently and taking notes.

While not unusual in the US, that kind of transparency raises long-debated issues about the role of cameras in courtrooms.

There are two sides to this debate which both hinge on two fundamental tenets of the US constitution: the freedom of the press and the right to a fair trial.

Court TV believes its coverage of The People vs Derek Chauvin will uphold both of those constitutional rights.

Hennepin County District Judge Peter Cahill issued an unprecedented order to allow cameras in the courtroom

"The death of George Floyd has galvanised people around this idea that there needs to be changes to the system," Michael Ayala, a senior Court TV presenter, told the BBC.

"What cameras allow us to do is give people a window into the courtroom so they can see how the process works. Perhaps in that way it will give them some confidence in the system."

This is one version of the argument made by Hennepin County District Judge Peter Cahill. He permitted filming of the trial in a landmark ruling last November. In that order, he cited intense public interest and Covid-19 limitations on courtroom access as his main reasons for overriding Minnesota's restrictive policies on filming trials.

Read more about Derek Chauvin's trial:

EXPLAINER: Why is the trial so important?

ANALYSIS: What do we know about the jurors?

A civil rights group leader explains the challenges of selecting a jury

Still, the decision was challenged by the lead prosecutor, Attorney General Keith Ellison. He argued that televising the trial would compromise the privacy of witnesses, thus exposing them to intimidation and influencing the course of justice.

Media companies, and ultimately Judge Cahill, did not agree. Nor did Jane Kirtley, a professor of media ethics and law at the University of Minnesota.

"The vast majority of states allow cameras in courtrooms," she told the BBC. "The criminal justice system has not collapsed as a result of this. As a matter of fact, I think public understanding has been heightened."

Court TV has a team of technicians operating and monitoring the cameras from outside the courtroom

It was these kinds of arguments that enabled Court TV to dominate the cable airwaves with gripping legal melodramas for much of the 1990s and 2000s. Run by lawyer cum journalist Steven Brill, Court TV blurred the lines between hard news and entertainment, making household names out of criminals and victims who were otherwise unexceptional Americans.

Having relaunched under new ownership in 2019, Court TV sees the Chauvin trial as more than a throwback to those glory days.

"We're advocating for more access so that people can watch their justice system work," Grace Wong, Court TV's director of field operations, told the BBC. "At a time when disinformation is so prevalent, transparency is the antidote."

The Chauvin trial, she added, is "a return to our mission, our mission is to give people a front-row seat to justice".

To sceptics of cameras in courts, this tagline strikes a familiar tone.

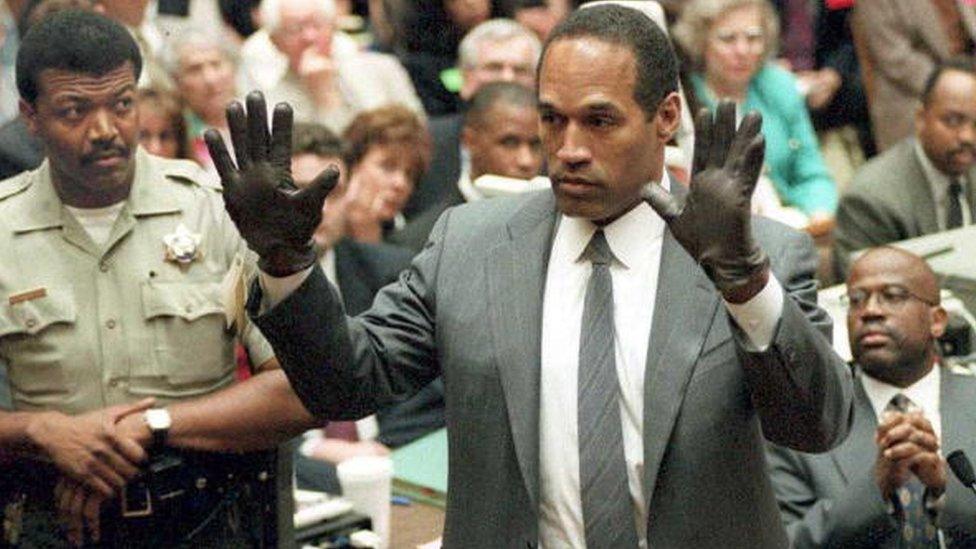

The trial of American football star OJ Simpson in the 1990s shows us why.

Gloves found at the crime scene were a crucial element of the OJ Simpson trial

The OJ Simpson trial in Los Angeles was a watershed moment for TV court cases. While cameras had been in courtrooms since the 1980s in the US, the OJ trial gave birth to "a new kind of genre of television", said Paul Thaler, a media scholar.

This was a trial that captivated a nation for eight months, courtesy of (you guessed it) Court TV. It had all the ingredients of a made-for-TV thriller - two grisly murders and a humbled celebrity in a city torn by racial strife.

Mr Thaler said television "impacted everything related to that trial", which resulted in Simpson's acquittal in 1995.

3cameras in the courtroom

14hours of trial coverage each day

62editorial staff working on the trial

112 millionUS homes with access

25 millionUK homes with access

In any high-profile criminal trial, there is a court of law and a court of public opinion.

"These two merge during a televised case," Mr Thaler, who wrote two books about cameras in courtrooms, told the BBC.

"Then there's the question of how much public opinion comes into the courtroom, not only for the witnesses, but for the lawyers, the judge and the jury.

"If Court TV believes the massive publicity will have no impact on the [Chauvin] case, I think that's naïve."

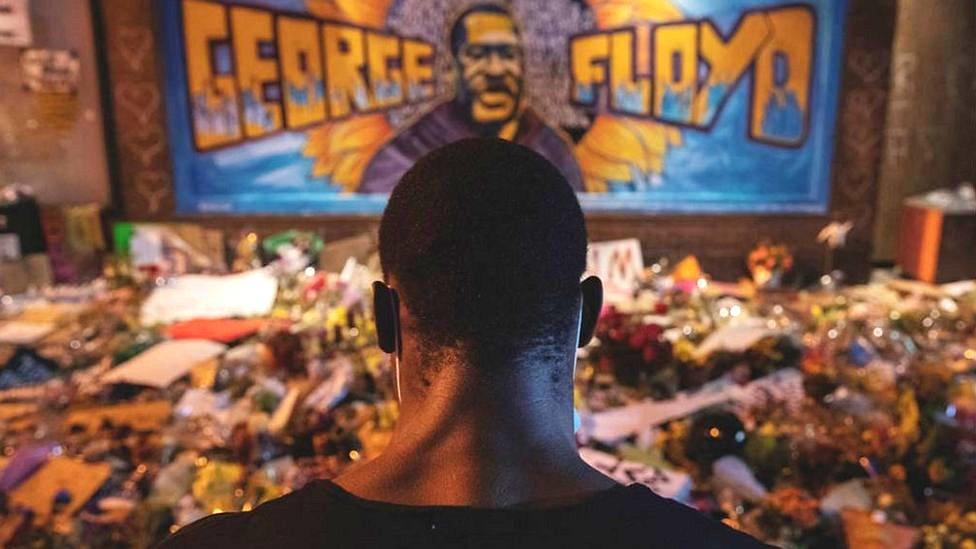

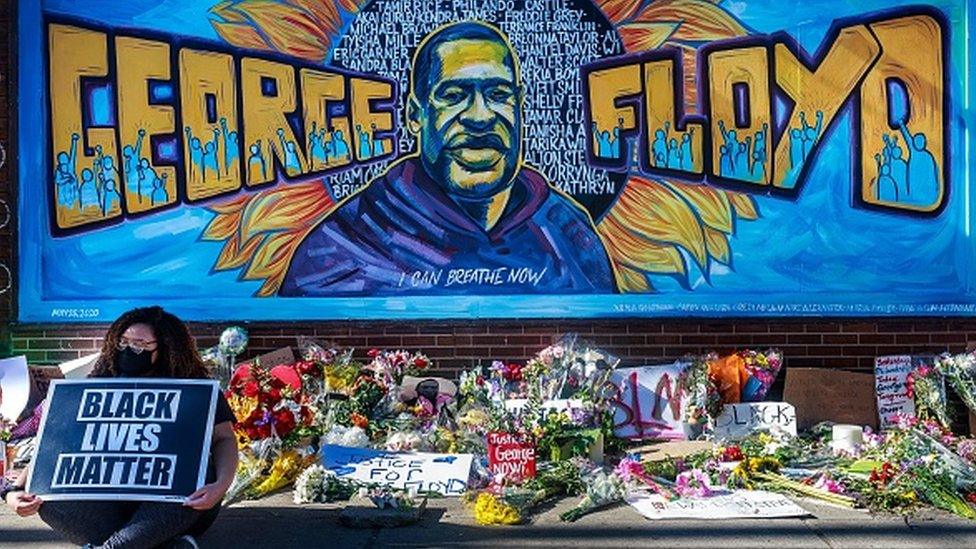

Black Lives Matter protests erupted worldwide in the wake of George Floyd's death

There are notable differences between the OJ and Chauvin trials, of course. For a start, the cameras cannot zoom in or out on anyone in the courtroom. They can't show Mr Floyd's family, or any of the witnesses without their permission, either. Those restrictions will moderate the soap-opera instincts of Court TV, taking the emotional edge off its coverage.

But none of that matters to Mr Ayala. For him, the seriousness of the trial for race relations in the US will transcend the appetite for a spectacle.

"This trial is about something much more important. It's about a movement. It's about a time in our country when we're trying to figure out race relations.

"At the centre of it, race is the elephant in the room."

Key figures in Derek Chauvin's trial

1) Derek Chauvin's lawyer Eric Nelson

He is a Minnesota-based lawyer with a focus on defending clients in criminal cases

He was appointed to Mr Chauvin's case by an association that provides legal services to Minnesota's police

He has represented many police officers, often those involved in shootings

One of his biggest cases involved the wife of a professional American football player, Amy Senser, who was jailed over the hit-and-run death of a chef in 2011

Mr Chauvin's lawyer has kept a relatively low profile ahead of the trial

2) Hennepin County Judge Peter Cahill

He is an experienced judge with a track record of presiding over high-profile trials in Minnesota

He has been described as a fair, bold and decisive judge

He was appointed as a judge in 2007 and has been elected to the post three times since

Before that, he was a prosecutor and a defence lawyer, serving as top adviser to US Senator Amy Klobuchar when she was a county attorney

3) Attorney General Keith Ellison

He was a defence lawyer and a politician before being elected as Minnesota's first African-American and Muslim attorney general in 2018

He spent the early years of his legal career specialising in civil rights

In Congress, as a representative for Minnesota, he was seen as a rising star of the Democratic party's progressive wing

He took over the George Floyd case as special prosecutor in May 2020, at the request of the state's governor

Keith Ellison was the first African-American representative from Minnesota in Congress

4) The jury

A jury of nine women and six men have been selected for the trial

The jury includes six white women, three black men, two multi-racial women, three white men and one black woman

Their names have been kept confidential and they won't be filmed during the trial

Of those jurors, 12 will decide whether to convict or acquit Mr Chauvin of the charges against him

- Published11 June 2020

- Published2 March 2021

- Published2 September 2020