George Floyd death: How US police are trying to win back trust

- Published

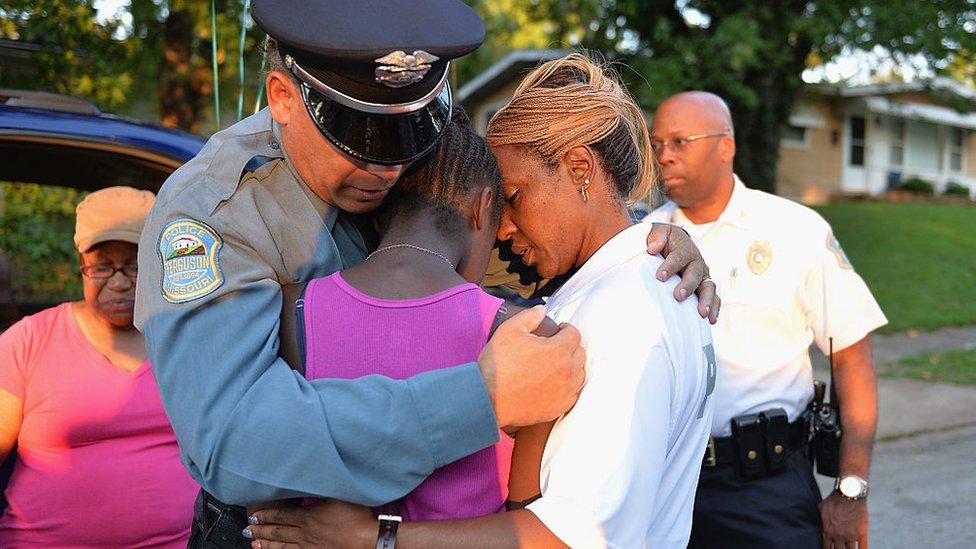

Police officer in Ferguson consoles a bereaved family

It must be hard being a police officer in America, especially after the death of George Floyd.

Damn right too, some would argue, given the shocking video of his last moments alive.

Patrol woman Brittany Richardson is 34 and a 12-year veteran.

She's now with the Ferguson Police Department, a suburb of St Louis in Missouri, and was at home with her wife and two children when she first saw the images of Derek Chauvin's knee on Mr Floyd's neck.

"There were so many videos of police engaged in the wrong kinds of interactions with people," Brittany says, "but this was heartbreaking."

The police are not all like that, she says, but the public don't see the men and women in uniform as individuals. "If one cop does something like this, we're seen as all the same. I was watching on my phone and I just kept thinking 'why is he on him, there's no need for this'.

There was no need for that amount of force, she says.

"I couldn't believe what I was seeing. Watching my wife's reaction, she was saying the same thing the rest of the world was saying. Why, just why?"

Look at us as individuals, urges police officer Brittany Richardson

Brittany takes me out on patrol with her. Ferguson isn't very big - typical smalltown America. Easy on the eye.

"It's hard to believe that on television this place looked like a war zone," I suggest, gazing out of the window from the passenger seat at little white picket fences and manicured lawns.

"Yeah that was a lot of trouble that went on for weeks."

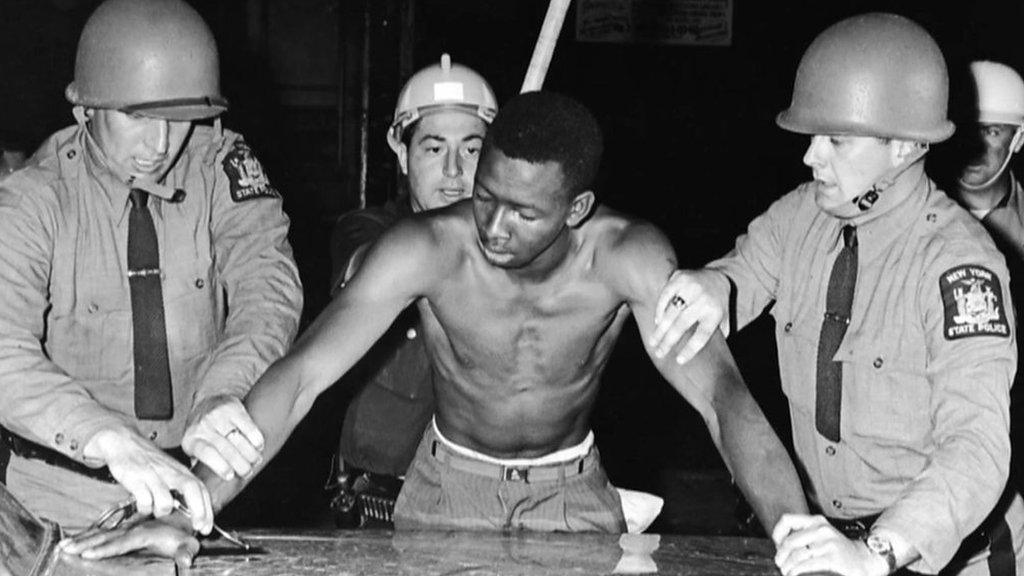

She's referring to the nightly pictures beamed around the world of the running battles between riot police and protestors in 2014, following the killing of the African American teenager, Michael Brown, who was shot six times by a white police officer.

Pictures show his body lying in the middle of the road in a pool of blood. His sneakered feet poking out from beneath a white blanket.

"I'd been a police officer for about five years up to that point, and looking at Facebook isn't a good idea, when there's been a police killing" Brittany shrugs.

George Floyd death: What’s changed, 100 days later?

"It was the same after George Floyd died. You see comments like - all the police want to do is kill us. But that's not what it's about, being a police officer."

Up ahead, we see a liquor store on the corner of the street.

"Watch this," Brittany says, "you see those five cars parked outside, as soon as we pull up, they'll drive off."

Sure enough, that's what happens, the vehicles scatter on the arrival of the patrol car.

"The drunks don't like me hanging around," she says "in case they do something stupid. But I worry every day that someone will pull out a knife or a gun and I won't go home back to my kids and my family at night."

"Do you pray before you go to work?" I ask. "Yes, every day. I pray outside the room of my kids that they'll be safe, and to make sure they know they're loved, and I pray I return home to them."

The death of Michael Brown was investigated by President Barack Obama's Department of Justice and they cleared the police officer of wrongdoing on the basis of witness statements and forensic evidence.

But it was scathing about the Ferguson Police Department and its report led to the resignation of the police chief. To this day the force must adhere to a strict set of rules governing how it conducts its business.

The current Ferguson police chief, Jason Armstrong, has been in the job for two years, trying to maintain a steady course on the road to the force's redemption.

"We're doing what we can," he says. I cannot guarantee or promise you there won't be another police shooting, of course not, but what I can promise and guarantee, is that we are going to handle that problem the right way, that there will be accountability. Only time can build trust, but we're getting there."

No police shootings since 2015, says Ferguson police chief Jason Armstrong

But what about the fabled "blue wall of silence", that unbreakable bond between cops? It used to mean your buddy's got your back in a shoot-out, but it also meant he or she had your back if you did something stupid, or wrong, or even illegal. In other words, they'd lie to cover for you.

"We have new disciplinary procedures," says Chief Armstrong. "Our Duty to Report policy means that if an officer sees a colleague engaged in activity that would discredit the force, then they're duty bound to report what happened, and failing to do so could result in penalties similar to those imposed for committing the offence itself. "

It is a long road to the atonement past police injustices require. But Chief Armstrong says there hasn't been a single police shooting in Ferguson since Michael Brown died. No officer has had to discharge their weapon.

The chief was taking part in a fun run on the day I arrived in St Louis, jogging alongside local people. A different kind of community policing on a sunny Saturday afternoon. No big deal, no great fanfare, but the visible manifestation of a sense of community the police department is trying to foster.

The town sits next to the city of St Louis, the US murder capital and the worst place in America for civilian deaths at the hands of the police. I meet patrol officer Jay Schroeder, in the bar of the St Louis Police Officer's Association.

He's the president, and on the walls in four large frames are passport style pictures of 166 St Louis police officers. Each one is dated, the first in grainy black and white is of a man called John Sturdy. Beneath his name are the letters EOW, which stand for End of Watch, and the date he died - 1863.

Jay Schroeder (right) shows the BBC's Clive Myrie tributes to fallen officers

Jay says several of the officers whose pictures are on the wall died in the late 19th, and early 20th Century and were victims of electrocution, after trying to use the cast iron police call boxes, which were poorly designed. But many others were shot in the line of duty.

"That's Gregory Erson," he says looking at one photograph, this time in colour. "He was working in vice and was ambushed by a prostitute's pimp. EOW-1983.

"Four of these guys I worked with, and Norvelle Brown- EOW August 2007, was the first who was shot and killed. Murdered after being fired on from inside a house where he was attending an incident. He didn't stand a chance."

I gently make the point to Jay that the city of St Louis has the highest level of civilian deaths at the hands of the police, anywhere in America.

"Yes but it is a dangerous place with violent crime rising," he counters. "But we understand public concern and we've been trying to work better with local communities, and we were doing good. Then George Floyd happened, and that set law enforcement back across this country. Sometimes things look bad on video. This one was bad, and for all the progress we've made since Ferguson, it wiped it out, just like that."

Jay comes from a family of police officers, six generations to be exact. His great, great, great, great, great grandfather emigrated from Ireland to America in 1891 and joined the police force, and there's been an officer from the Schroeder family in the ranks continuously, ever since.

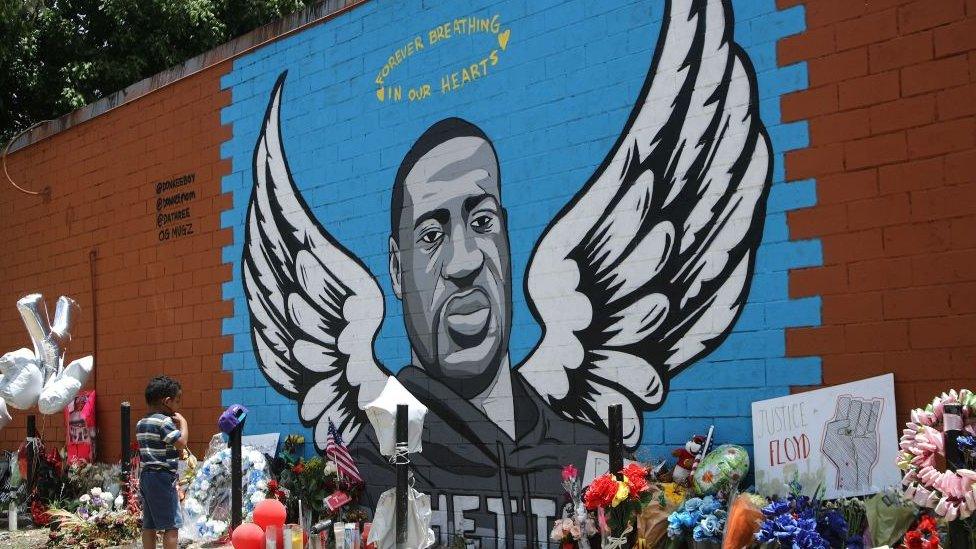

As America marks the one year anniversary of George Floyd's death, it's not just civilians who'll be reflecting on what happened.

The police will be too, determined to show that Derek Chauvin does not represent who they are.

You may also be interested in:

What happened when a city disbanded its police force

- Published18 May 2021

- Published5 June 2020

- Published18 June 2020

- Published13 June 2020

- Published26 June 2020

- Published21 April 2021

- Published21 August 2014