Why my mother won’t leave Ukraine to join me in US

- Published

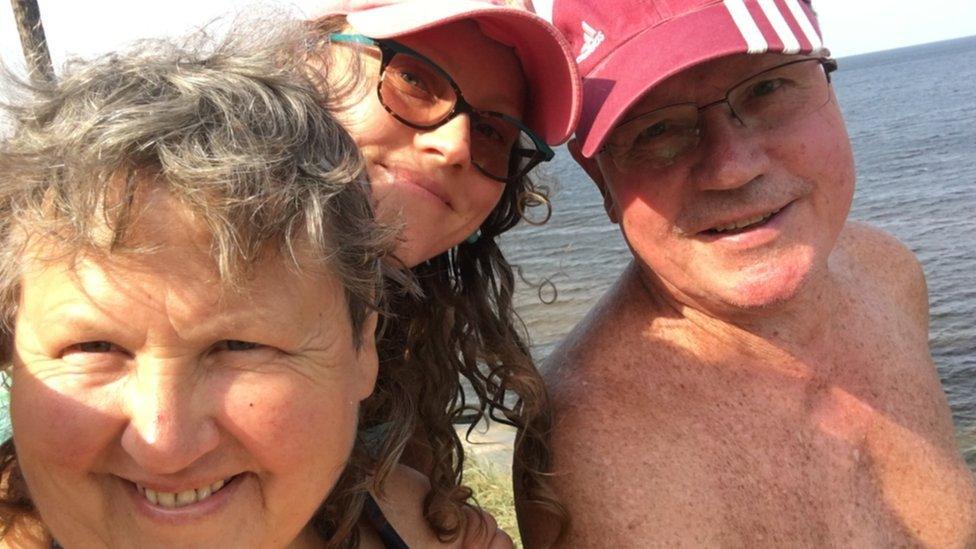

Yulia with her parents, together, in happier times

Yulia Popova wants her parents to get on a plane from Ukraine and join her in safety in the US. They have other ideas. Ideas that 100,000 Russian troops on amassing on the border won't change.

"I have not seen my mother for two years. During this time, I gave birth to a daughter, Covid spawned two new variants and Russia spewed a new military threat that sent US diplomats packing.

I want my mother to pack her suitcases too and join my family in Colorado. She is in Kyiv, Ukraine's capital, and the country is facing an imminent threat of invasion. I'm a US citizen who wants her family safe and away from the geopolitical games of a mighty few.

But my mother - who has a US visitor visa - says "no" to leaving.

The Russian threat is not new to Ukraine. For as long as Vladimir Putin has been the Russian president - 18 years and counting - Ukraine and other former Soviet Union states have seen disputes over leadership and borders.

But with 100,000 Russian troops amassed at Ukraine's eastern gateway, the imperial blackmail now feels more real to many.

Russian troops conduct combat training on the Ukrainian border

My mother, 65, is not in good enough health to get on the plane by herself and leave. My dad, 75, does not have a US visa yet. That is why they cannot leave, but it is not really the reason they want to stay put.

My mom comes up with various excuses: she wouldn't fly alone, she wouldn't leave my dad behind, her child-rearing techniques would clash with mine and then what about Murchik, the cat? I am scarier than Mr Putin, it seems. She doesn't think the threat is real.

I give up my line of reasoning and ask about dad.

"Your dad is always waiting for war," my mom says, which is true.

My dad is intensely interested in what happens between Ukraine and the Kremlin. He says an all-around invasion would be insane and highly unlikely. And anyway, if it happens, "They [the Ukrainian government] will just give everyone weapons and it would be a bloodbath on the streets," he adds.

What he means is that Ukrainians will not give up their independence easily.

My mom is interested in different things, such as the price of cooking oil, which is three times more expensive than last year - and if they should withdraw their savings.

I tell her they should, knowing it would hurt the economy if everyone else starts to do it too, but it could buy my folks a plane ticket if they need one

Ignoring my parents' lack of urgency, I venture on the US Embassy in Ukraine website to apply for a visitor visa for my dad, where I learn that the usual wait time of three months is now almost a year.

I also learn that the US Embassy held an auction in the first week of January to sell off furniture, computers and whatever else could weigh them down. Two weeks later, the US would withdraw all their staff from the embassy. "Why do they make it look like another Afghanistan?" is my knee-jerk reaction.

Life continues as usual in Kyiv despite the threat of war

Around the same time, an old friend from Kyiv contacts me to ask if I know anything about business visas to the US.

Like me, she's in her late 30s, with a husband who works in tech, and they are both "shaken up".

She tells me that many of their colleagues sent their families out of Ukraine in December when the Russian troop build-up began. When the prospect of negotiations with Moscow seemed to be going well, they came back in early January.

Many have now apparently left again.

Wealthier Ukrainians "urgently look for real estate abroad to buy or rent long-term," my friend adds. She lost faith in Ukraine's safety and stability many years ago, but her husband was committed to his tech business. The current winds of change may finally spell out immigration for them. "We just want to finally sleep well at night," she says.

Ukraine is a country of a dwindling 44 million people. Scores have emigrated in the past two decades, though millions travel back and forth every year to Poland, Portugal and other European countries for temporary jobs in construction, agriculture and housework. Nothing stops them, not even Covid.

But the threat from Russia might mean a more permanent exodus.

Some will stay to fight Russia, of course. Others don't think they have much to lose - my mother is in their ranks. "Putin or Zelensky, it doesn't make a difference who's in charge anymore," she sighs. After a decade of revolutions, inflation and economic instability, I can't blame her for thinking this way.

And then there are those who say everything's under control. "There is no reason to panic," Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky declared in January. He sounded confident - but his message withered quickly when President Biden takes the stage and says Russians will most likely attack. "

Watch the BBC's Sarah Rainsford as she tries to track down official bomb shelters in Kyiv

Related topics

- Published28 January 2022

- Published27 January 2022

- Published16 November 2021

- Published10 September 2021