Midterms turnout: Could Australia-style voting help in US?

- Published

The turnout next week for the US congressional elections could be a record, although it will still fall below many other countries. Could Australia have a solution?

When Americans went to the polls for the last midterm election, they did so in unusually high numbers. Unusual, that is, by American standards.

According to the US Elections Project, 50% of the voting-eligible population cast a ballot in 2018, the highest midterm turnout since 1980.

With close contests and high interest nationwide, Americans may beat that 2018 mark this cycle. Even so, it would pale in comparison to voter participation levels recorded in other democratic nations.

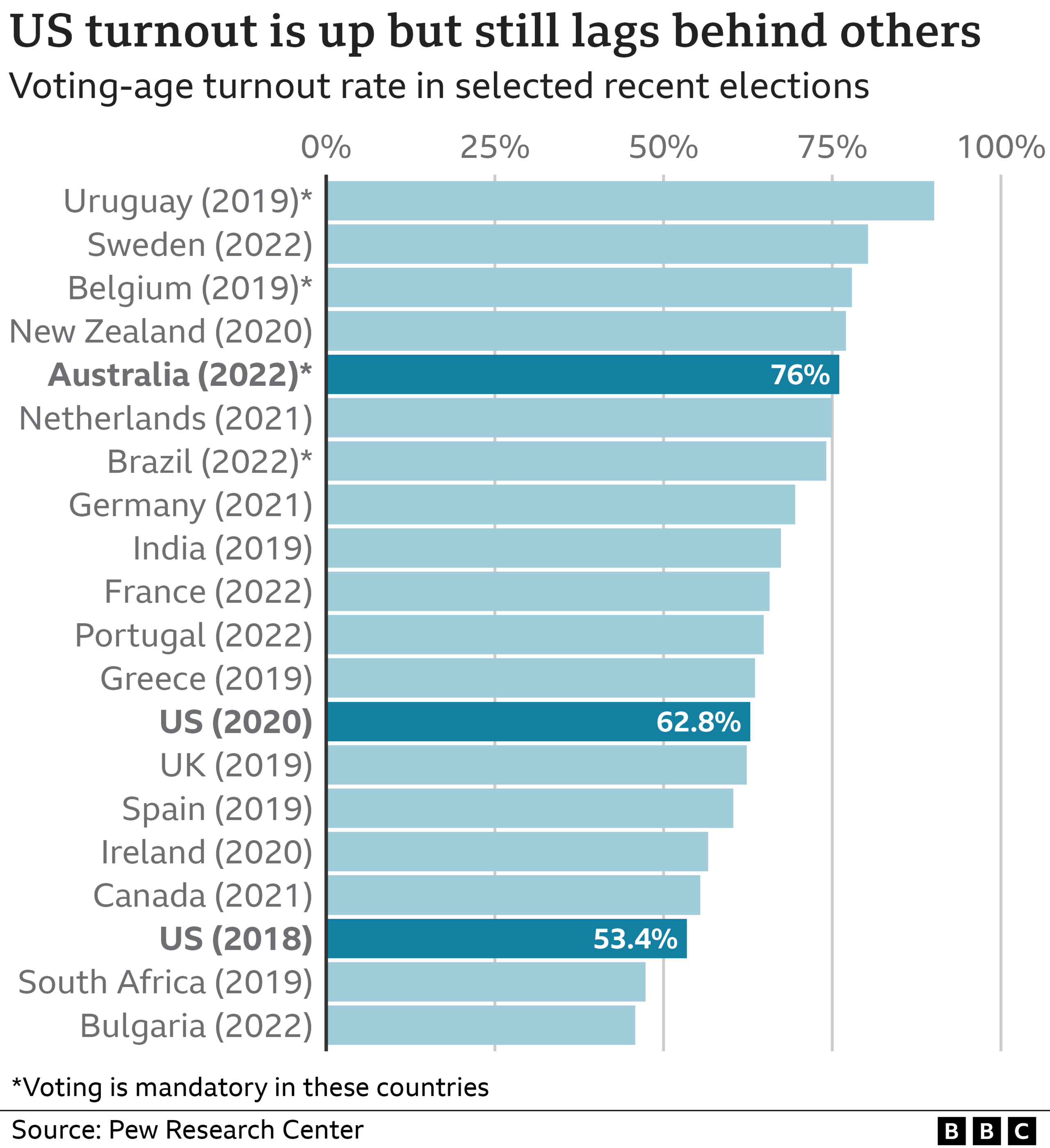

Of 50 countries examined by Pew Research, the most recent nationwide election data shows the US ranks 31st in voter turnout. And that figure - 62.8% - was from a presidential election. Midterm election turnout tends to be significantly lower.

The US "consistently comes around the middle or slightly below the middle compared to this peer group of countries," says Drew DeSilver of Pew.

One key reason is voter registration, he says. A lot of countries register voters nationally and some automatically enrol them when they reach voting age, while others aggressively push the idea of registration.

In the US it is done differently in each state and citizens often have to seek out registration. And if they move home, they have to register again. Americans who are registered to vote tend to vote in really high numbers so, DeSilver concludes, if it was easier to register, more Americans would vote.

No such problem in Australia, which is one of the only English-speaking nations that has compulsory voting. In the US, Canada, New Zealand and the UK, voting is voluntary. And that's reflected in the turnout, where Australia is one of the highest.

Since it was introduced in 1924, all eligible adults have been required to get their name crossed off the electoral roll on polling day. Elections are always held on a Saturday, to make that easier. Failing to vote without a "valid and sufficient reason" results in a fine of A$20 ($12.57, £11.36).

But there are workarounds. Some people are eligible for exceptions, and a small cohort of people - less than 5% - simply cast blank or defaced ballots, which are known as informal votes.

It means the vast majority have their say, which is great for democracy in several ways, says historian Judith Brett.

"Speak to people, particularly Americans, and they think it's undemocratic, whereas Australians think it is democratic."

Compulsory voting means politicians cannot win without the support of the majority including groups that are traditionally less likely to vote - like the poor, less educated, or immigrants. Ms Brett argues their inclusion makes for fairer and "more egalitarian" public policy.

Compulsory voting also helps moderate politics, she argues. Parties that have to motivate their supporters to take the trouble of going to the polls can be tempted towards "much more extreme" political issues.

"When Donald Trump was elected in the United States and Britain had its vote on Brexit, lots of people in Australia comforted themselves with the thought that, because we had compulsory voting, that sort of populist result - which is how people in Australia saw it - was much less likely to happen," she says.

On the other hand, some argue compulsory voting makes politicians complacent, because they don't have to work as hard to inspire people.

"They take their voting blocks for granted," says politics professor Ian Tregenza. And voters go through the motions, with some casting votes despite being disinterested and uninformed. But he believes compulsory voting works against apathy.

Australians have comparatively high levels of basic political engagement thanks to its system, he says. "If they removed compulsory voting in Australia tomorrow, I think we would still have pretty high [voting] rates." He believes they might match New Zealand, which at its last election measured nearly 80%.

The ultimate argument against compulsory voting is that the right to vote should entail the right not to, he says. "It's based on that principle of individual rights."

Very few Australians agree. Polling shows compulsory voting has widespread support and there are few high-profile opponents. One was former Finance Minister Nick Minchin, who pushed for voluntary voting in 2005.

More on this series, Seeking A Solution

As Americans prepare to vote we are visiting countries around the world looking for answers to challenges facing the US political system

We are tackling subjects like an ageing Congress, gridlock in passing laws, a lack of female representation and low turnout

Reporters in Norway, Bolivia, Finland, Australia and Switzerland will explain how these issues are handled where they live

But Prime Minister John Howard shut down the issue, saying while he personally supported the cause, he recognised the clear majority of Australians didn't.

So could a compulsory system work in the US? Drew DeSilver of Pew Research thinks not. "I would be sceptical that it would ever fly in this country."

He can't envision it ever happening because making basic changes to federal election law is really difficult and has very little chance of passing Congress.

A better way to boost turnout, he believes, is to increase registration because nearly all Americans who are registered, vote.

"The easier we make it for people to vote," he says, "the more people are going to vote."