Children from Calais jungle camp will be allowed to stay in the UK

- Published

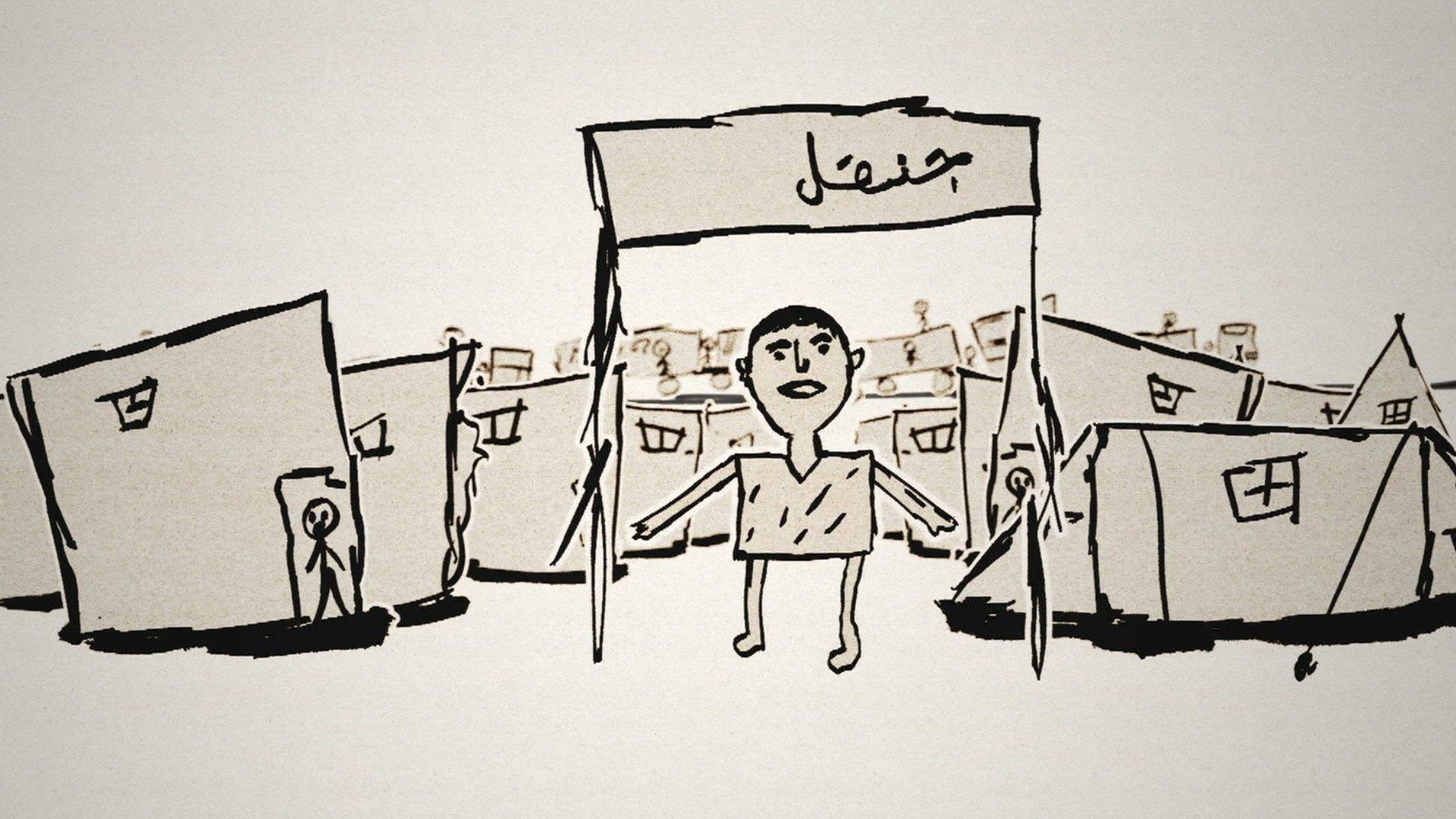

This was what part the camp looked like in November 2016 before it was demolished, as containers are put into place

Children brought to the UK from the 'Jungle camp' in Calais, France, will be allowed to stay living here, the British government has promised.

Before it was demolished in November 2016, it was one of the biggest refugee camps in Europe.

Immigration minister Caroline Nokes announced on Thursday that more than 200 young people from the camp, who came to the UK to join family members, will be given a new status.

This will allow them to study and work in the UK, and access the National Health Service care.

Although many have been refused asylum in the UK, this move means these young people will have a "leave to remain" status in the country.

They will then be able to apply for citizenship in 10 years' time.

Millions of people - many of them children - were forced to leave where they lived because of fighting in the Middle East.

In particular, the conflict in Syria drove millions of people from their homes. It also meant lots of families got separated from each other.

Many travelled to Europe, in the hope that they might find a better life in a European country, with many hoping to come to the UK.

Martin went to Calais in August 2015 to find out more about the migrant problem there

But some groups say this decision is "unfair", because it only applies to those who were present during the camp's demolition, but not anyone who came to the UK before that date.

The scheme will also only apply to those young people who have recognised family ties in the UK.

More than 750 unaccompanied children were brought to the UK from the makeshift camp.

About 220 were transferred under the Dubs scheme - a special piece of European Union law, called the Dublin III regulation, that says that families have a right to stay together.

Another 550 went to live with family already residing in the UK.

Over the past two years the majority of these children were given the right to remain in the UK under existing international protections such as asylum, humanitarian protection and refugee status.

Take a look at Omar's story...

However a small group weren't, and so would have faced deportation as soon as they turned 18 under existing immigration rules.

The government has now stepped in with these new measures to give them a status and protect their rights in the future.

But Safe Passage, a charity that help unaccompanied child refugees and vulnerable adults find safe new places to live, say the news is not all good.

Beth Gardiner-Smith from the charity says that under the new form of leave, children will have to wait twice as long to apply for indefinite leave to remain than those who have been recognised as refugees.

"Regardless of how they arrive, vulnerable children that claim asylum in the UK should all be able to access a fair, consistent and human legal system that offers them long term safety and security," Ms Gardiner-Smith said.

- Published2 November 2016

- Published2 November 2016

- Published26 May 2016