Gender Stereotypes: Why do shops divide products for girls and boys?

- Published

- comments

Have you ever been into a shop and wondered why the shops are divided into aisles for girls and aisles for boys?

Or have you ever thought to yourself, why are girls' products often pink and purple, and boys' products black and blue?

There's a reason shops divide their products up in that way - and it's because they want to market toys, clothes and toiletries to specific genders.

Now the group that makes sure adverts in the UK are suitable and appropriate has said it will ban "gender stereotypes that are likely to cause harm, or serious or widespread offence".

The Committees of Advertising Practice (CAP) says harmful stereotypes in adverts "contribute to how people see themselves and their role in society", and can hold some people back.

But why does this happen? Is targeting adverts and products at boys or girls a good way to sell more products, or is it just sexist?

We want to know what you think. Don't forget to vote at the bottom of the article and to share your opinion in the comments.

Why do companies and shops divide products by gender?

How do you look for the aisle you want to shop in? Do you look by colours? Shapes? Textures?

You might not think that these are things that you look for, but when companies want to appeal to boys and girls, they try to make products that fit into what is often thought to be most attractive to the gender.

For example, toys marketed to girls are often coloured in shades of pink and purple because these colours are thought to be liked by girls more than boys.

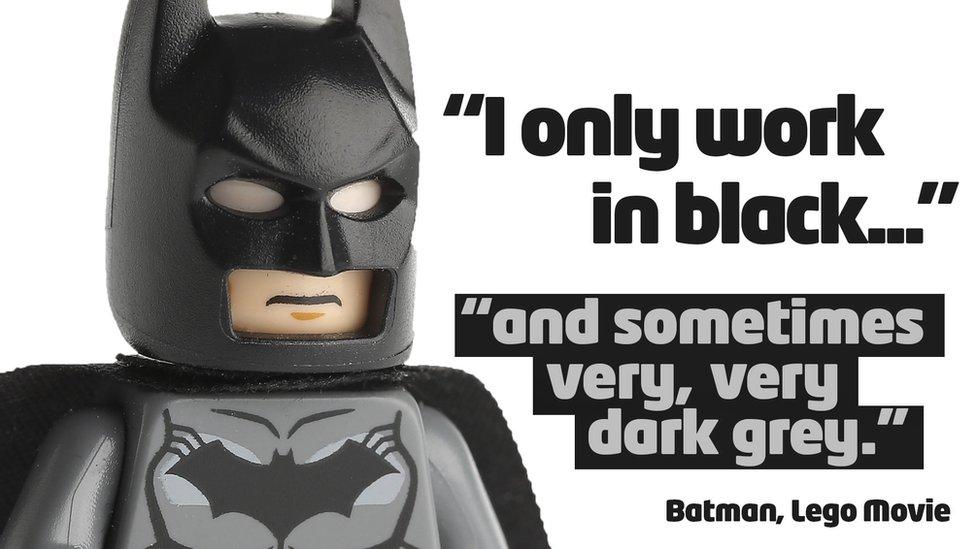

Toys marketed to boys are typically made to look more 'masculine' - they might be more associated with colours like blue and black and have harder, straighter edges.

But, do all the differences stop there?

Lots of toy creators believe that marketing to a specific gender, instead of across both genders, might help sell more toys.

This is partly because some studies have shown that boys and girls tend to prefer different toys to each other.

A famous example of this is when Lego released their Lego Friends product range - designed to appeal to girls.

The Friends products had a greater focus on play in restaurants, shopping and houses than the traditional Lego sets.

Before these products were released, Lego stated that in 2011, 90% of their customers had been boys.

In the first sixth months of 2012, after the release of the Lego Friends product line, Lego's profits rose by 35%.

Construction had never worked for girls, for whatever reason...

Many people see this move by Lego as a good example of rethinking a product to help more girls connect with it.

But others were upset that Lego felt it had to create a 'stereotypically feminine' toy to encourage more girls to buy their products.

In creating the product range, Lego claims it spoke to 3,000 girls to ask their opinions on what they wanted.

But in 2014, a debate was started after 7-year-old Charlotte wrote to Lego after she was disappointed with their range of products for girls.

She was upset at the way that she thought that the female Lego characters were shown.

In her letter, Charlotte said the Lego marketed towards girls often focused on the characters staying at home or going to the shops, whereas the Lego marketed to boys' was much more exciting.

All the girls did was sit at home, go to the beach, and shop, and they had no jobs but the boys went on adventures, worked, saved people, and had jobs, even swam with sharks.

Gender stereotyping in toys goes both ways - many toys for boys only come in dark colours which are considered more 'masculine'.

Charlotte's letter sparked a debate about whether marketing toys to girls and boys separately was sexist.

Some feel that it forces children to connect with ideas that are old-fashioned or unrealistic.

For example, not all girls like pink or enjoy playing with dolls.

And similarly, not all boys like robots or playing football.

The issue seems to be that marketing to different genders can sell more products, but some people believe that this often supports negative stereotypes.

Sexism is where people judge or have expectations of others based on their gender.

Often it is the idea that one gender is better than the other gender at particular things.

"Boys are better than girls at sport" is an example of sexist statement.

What kids think about sexism in adverts

It's not just toys that have sparked debate over the division by gender.

Clothes shops are often criticised for the text they put on their clothing.

We went to investigate clothes shops to see what they had on offer for boys and girls. Here are some pictures of the t-shirts we found. Who do you think each of these t-shirts are designed for?

In 2017, parent Shelley Roche-Jacques was angered after spotting a selection of t-shirts in Morrisons supermarket.

One t-shirt carried the slogan like 'Little Man, Big Ideas' while the same style of t-shirt marketed to girls said 'Little Girl, Big Smiles'.

She was upset as she felt that the t-shirts suggested that boys are more likely to have important ideas and thoughts, while the matching t-shirt suggested that girls' outward appearance was more important.

Two different bottles by the same manufacturer. What differences can you spot between the styles of the bottles? Who do you think they're for?

Some toiletries manufacturers have said worry about their products being 'too feminine' for men to buy.

Personal care brands often add words like 'men' or 'for men' to soaps, body washes and moisturisers to make it clear they are more 'masculine'.

And whereas women's products tend to focus on more floral names, men's products will focus on ideas around energy or action.

Where do the stereotypes come from?

In 2012, pen manufacturer BIC was heavily criticised for releasing a pen designed just for women. Many people felt that creating a pen 'for her' was patronising to women.

There is an argument that the products we use, and the adverts we see, can influence how we act and think about ourselves.

While some gender differences come from biological differences, we are also effected by what we see around us.

Because of this, some people feel that companies should more be careful about what they try to market to us, as it can influence the way we see gender.

But lots of companies also argue that their products are designed to appeal to what the customer wants, and not the other way around.

Toys designed for children 18 months old and up.

The generally accepted rule is pink for the boys, and blue for the girls. The reason is that pink , being a more decided and stronger colour, is more suitable for the boy, while blue, which is more delicate and dainty, is prettier for the girl.

So what came first?

Girls liking pink and boys liking blue?

Or companies telling girls that they should like pink and boys that they should like blue?

Historians have said that at the beginning of the 20th century, the preferred colour for girls in the West was blue and that boys were more often dressed in pink.

However, in the 1940s, manufacturers believed that girls preferred the colour pink and boys preferred blue - and so the colours for each gender were swapped.

This is despite a number of studies showing that adults of both genders tend to prefer blue to pink.

So what do you think?

Do you believe that the products you use are designed to match what you genuinely like?

Or do you think shops and their products tell you what to like based on gender stereotypes?

Let us know in the comments and don't forget to vote below!