Wildlife: Snakes starving because there aren't as many frogs for them to eat

- Published

- comments

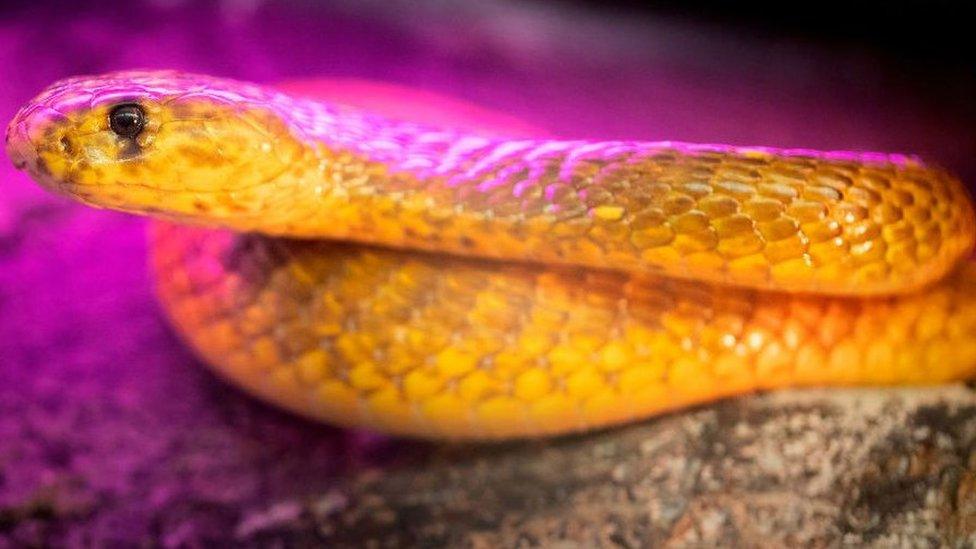

Seven green parrot snakes were seen before the fungus arrived, but afterwards none were found - making scientists think they might all have died

Snakes in Central America have been dying of hunger after huge numbers of forest frogs died in a short period.

That's according to scientists from the University of Maryland and Michigan State University.

Many snakes rely on frogs and eggs from other amphibians as part of their diet.

But more than 500 frog species have seen their numbers drop, with 90 species becoming extinct since 1998.

Extinction occurs when there are no remaining individuals of a species alive.

Animals that have not adapted well to their environment are less likely to survive and reproduce than those that are well adapted. The animals that have not adapted to their environment may become extinct.

In the following years, the number of snakes and the variety of species have become fewer and fewer.

The loss of all these frogs is down to a deadly fungus called chytrid.

It's been wiping out populations of frogs and salamanders around the world over the last half century.

This tropical poison dart frog is native to the exotic rainforests of Panama

It's had such a big impact, that it's been named the world's most destructive force in terms of biodiversity.

But until recently scientists didn't know just how much impact it had on the wider circle of natural life.

The research carried out in a national park in Panama compared seven years of data collected before the fungus hit, with the six years after it infected the park.

Before the fungal invasion, the scientists saw 30 different species, but afterwards could only find 21, and in far fewer numbers.

Karen Lips, who helped carry out the study, said the results show "there was a huge shift in the snake community".

Brown snakes were very badly affected - the scientists saw them 13 times before the fungus arrived, but none were seen after

She said overall the number of species was reduced, with many species being seen less and less frequently.

However a few of the snake species did increase in number.

She added: "Body condition of many snakes was also worse right after the frog decline. Many were thinner, and it looked like they were starving."

The researchers can't say exactly how many snake species decreased because sightings of snakes in the Panama park are rare.

But they are sure it was because of the loss of the frogs, rather than other environmental factors, with the park protected from habitat loss, development and pollution.

Elise Zipkin, one of the people involved in the study, says this news should matter "even to people who might not like snakes" because of the wider impact it could have on other animals.

Scientists are concerned about the change in birds and mammals

Another of the authors, Julie Ray, said: "It's got to be affecting the birds and the mammals, and everything else."

She added: "The snakes are so important for the environment, if you take them out, the whole thing can collapse."

But there are some glimmers of hope. A small number of the amphibian species have been showing signs of resistance to the fungus and other species are slowly starting to recover.

Meanwhile it's good news for snakes that don't eat frogs, who seem to have increased in number likely due to reduced competition for food from other snakes.

- Published16 May 2019

- Published6 September 2019

- Published27 September 2012