Malaria: Could building higher houses the spread of malaria?

- Published

- comments

This man has been helping to give out mosquito nets to people in Africa to help protect against malaria

Could raising the height of houses in Africa could help slow the spread of malaria?

A team of researchers led by Durham University have been investigating if taller houses could be the answer.

As part of their research they carried out tests on houses in Gambia, in Africa, and discovered that huts with floors three metres above the ground had 84% fewer mosquitoes than those on the ground.

Professor Steve Lindsay, who led the research, thinks there could be two reasons for this: "First, malaria mosquitoes have evolved to find humans on the ground."

"Second, at higher heights, the carbon dioxide odour plumes coming out of the huts are rapidly dispersed by the wind, so mosquitoes find it more difficult to find a person to bite."

What is malaria and how is it spread?

Malaria is a disease caused by a parasite, which is spread by a particular kind of mosquito - the Anopheles - which tends to bite people at night-time.

It's a huge problem in countries across Asia, Africa and South America.

Most cases occur in Africa and the disease can make people very ill, especially babies and young children.

In 2019, the World Health Organisation estimated that malaria killed around 386,000 people in sub-Saharan Africa, many of them children.

Despite this, most people survive malaria after a 10-20 day illness, but it is important to spot the symptoms early.

Fever, headache and sickness are all symptoms of a possible infection

What are other ways people can stop the spread?

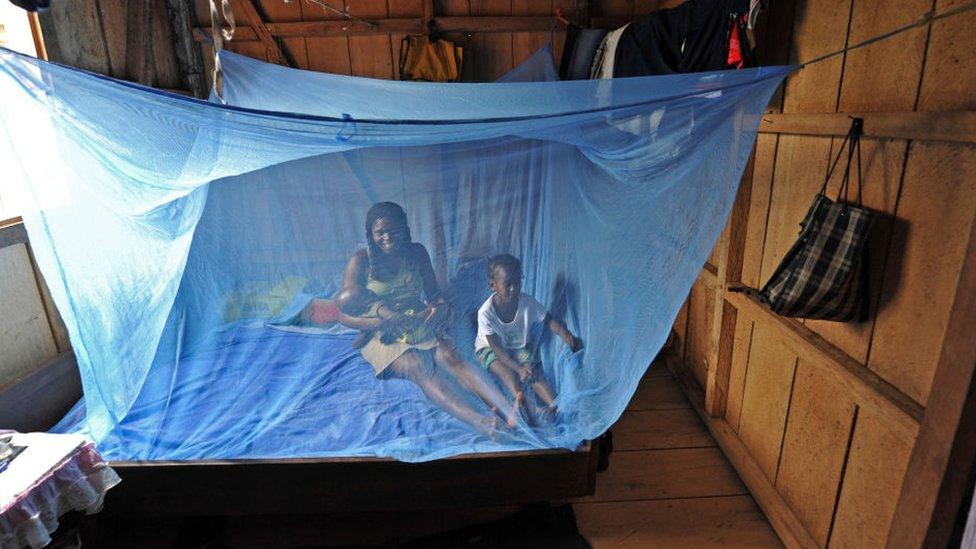

This family are using a mosquito net to help keep them safe

Malaria is a preventable and curable disease.

The best way to stop people from getting it, is to stop them from being bitten by the mosquitoes.

Things like special mosquito nets to cover beds, insect repellents and destroying mosquito breeding grounds all help to stop people getting infected.

Scientists are also working on creating a vaccine to help prevent and protect against malaria.

One vaccine, developed by scientists at the Jenner Institute of Oxford University, has shown to be up to 77% effective in a trial of 450 children in Burkina Faso, in Africa, over 12 months.

Bigger trials are now taking place, involving 4,800 children in four countries.

- Published23 April 2021

- Published3 December 2020

- Published25 April 2024