Algae powered computer created by UK scientists

- Published

- comments

The algae harvests energy from the sun through photosynthesis which generates an electrical current

Scientists have used algae to power a computer for a year using nothing but light and water.

The University of Cambridge researchers say the system could be a reliable and renewable way to power small devices.

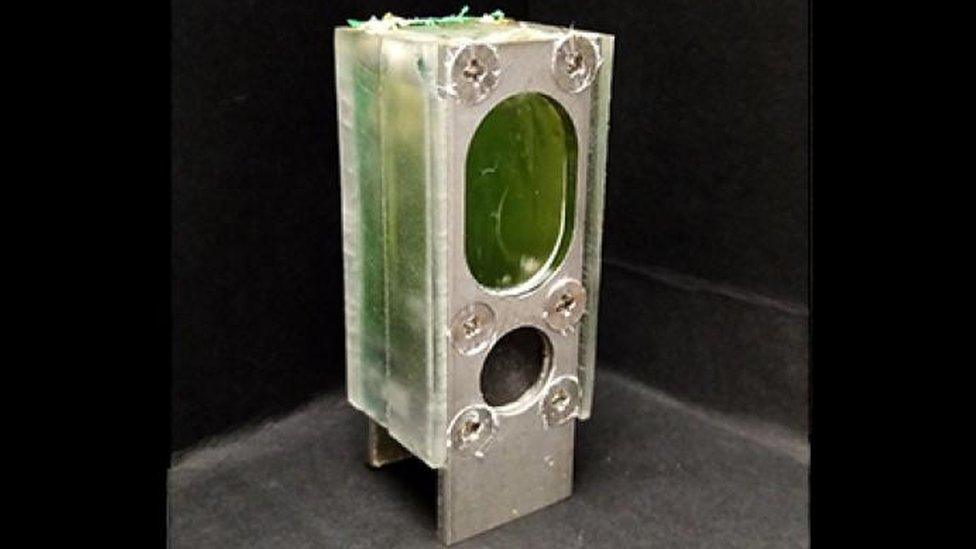

The system, which is about the size of a regular AA battery, contains a type of algae called Synechocystis.

So how does it work?

The algae naturally harvests energy from the sun through photosynthesis.

Photosynthesis is a chemical reaction that happens inside plants that help them create food as well as use up carbon dioxide and create oxygen which is very good for the environment.

This forms an electrical current which passes through an aluminium electrode and is then used to power the computer.

Because it is made of common, inexpensive things - water and algae - the scientists say it can be replicated hundreds and thousands of times.

It could be used to power small devices in the 'Internet of Things' - when lots of devices are linked together so that they can collect and transmitting data.

The Internet of Things is a huge network of electronic devices - each using only a small amount of power - that collect and share real-time data via the internet. For example a heating system in a house that tells the owner's smartwatch it's hot enough and it's going to switch off. By 2035 it's reckoned there will be a trillion devices like this, requiring a vast number of portable energy sources.

"The growing Internet of Things needs an increasing amount of power, and we think this will have to come from systems that can generate energy, rather than simply store it like batteries," said Professor Christopher Howe from the University of Cambridge's Department of Biochemistry.

He added: "Our photosynthetic device doesn't run down the way a battery does because it's continually using light as the energy source."

In the experiment, the device was used to power an Arm Cortex M0+, which is a microprocessor used widely in Internet of Things devices.

Scientists believe the system could create a renewable way of generating energy for things like smart watches

So far the device has been powered for a year and it hasn't stopped now!

Dr Paolo Bombelli from the University of Cambridge said: "We were impressed by how consistently the system worked over a long period of time - we thought it might stop after a few weeks but it just kept going."

- Published21 May 2020