Mystery of how flying reptiles took to the skies finally solved

Researchers are certainly flappy about their discovery!

- Published

They were able to flap their wings and rule the skies when dinosaurs roamed the Earth.

Now the mystery puzzling researchers - how winged reptiles called pterosaurs were able to get their air miles - has finally been solved.

It's all thanks to the help of the latest laser technology.

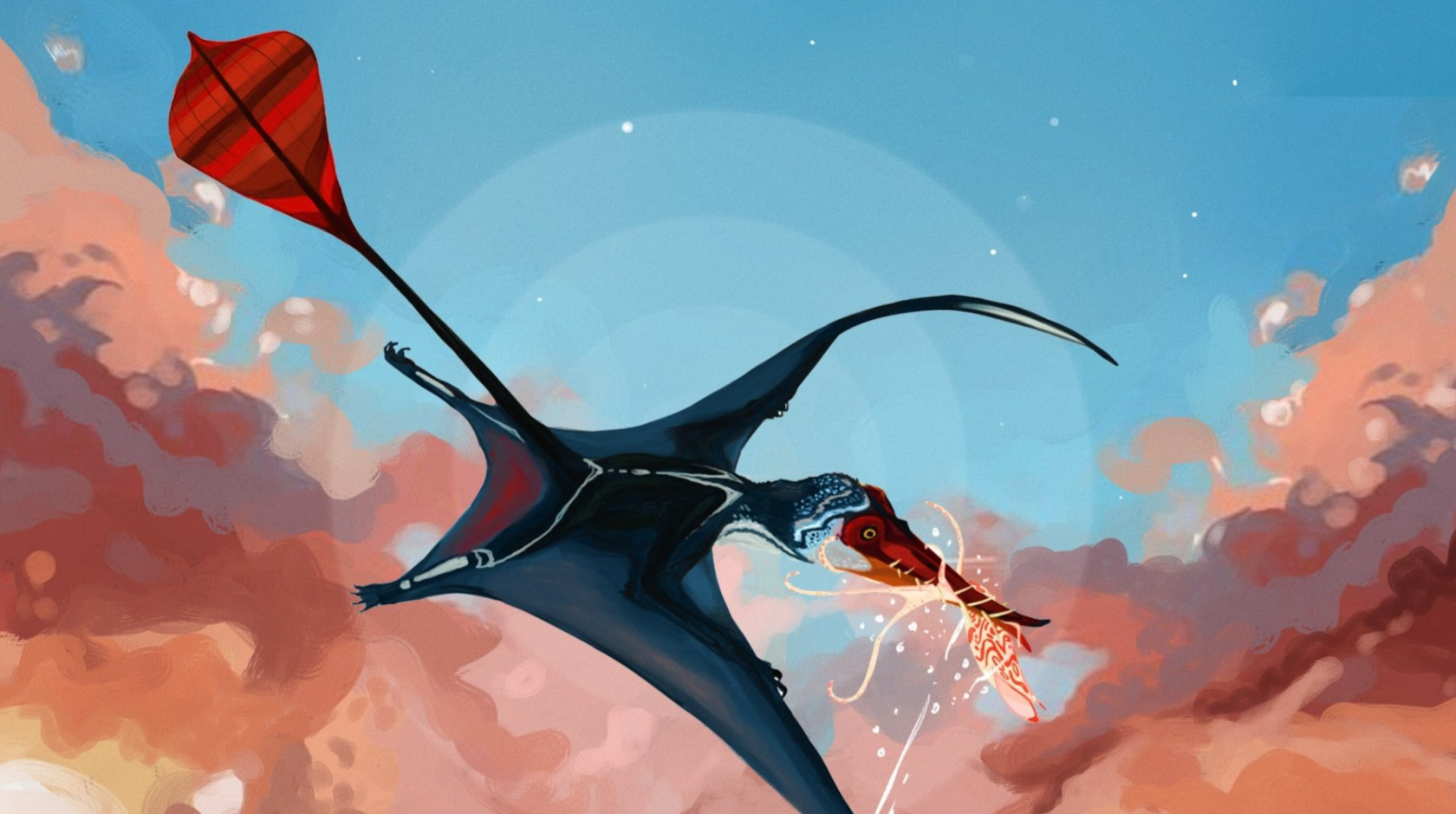

A team of palaeontologists from the University of Edinburgh have discovered the creatures had large "vanes" at the ends of their tails that acted like sails to steer them through the air.

More prehistoric stories

Some pterosaurs soared while others flapped, new research shows

- Published6 September 2024

Isle of Wight dino is 'most complete' in more than 100 years

- Published10 July 2024

'Oldest EVER' dinosaur fossil found in Brazil

- Published8 August 2024

The 'tails' they could tell!

What are pterosaurs?

Pterosaurs, commonly known as pterodactyls, lived around 225 million years ago.

They thrived for more than 100 million years - and there were lots of different species.

Pterosaurs evolved separately from dinosaurs, although it is thought that pterosaurs, dinosaurs, and crocodiles are closely related and so belong to a group known as archosaurs.

According to the American Museum of Natural History, some pterodactyls were as large as a fighter jet, and others as small as a paper airplane.

They became extinct at the same time as the dinosaurs - during the Cretaceous period, around 65 million years ago.

What did researchers discover about the pterosaur tail vane?

The team at Edinburgh University made the breakthrough using a new technique called Laser Simulated Fluorescence, which causes organic tissues, almost invisible to the eye, to glow.

They used the technique on 150-million-year-old fossils of a pterosaur known as Rhamphorhynchus.

While there's not much left to study of prehistoric animals, apart from fossils, sometimes traces of tissues like skin can survive for millions of years.

They were the first and largest vertebrates - animals with a backbone - to fly through the air

Far from winging it, the researchers found the membrane of the reptile's tail vane and the structures inside "visibly popped up" when scanned by the laser.

They explained that the diamond-shaped structures prevented their tails from fluttering like a flag in the wind, and helped guide and stabilise them when flying.

Dr Natalia Jagielska, lead author from the University of Edinburgh, said: "It never ceases to astound me that, despite the passing of hundreds of millions of years, we can put skin on the bone of animals we will never see in our lifetimes.

"For all we know, figuring out how pterosaur membranes worked, may inspire new aircraft technologies."

More roar-some dinosaur stories

- Published2 January

- Published14 February 2024

- Published6 October 2024