Why the battle for UCI presidency matters to cycling’s future

- Published

Stories about sports politics are notoriously difficult to assess, follow and sell.

Sometimes they feel incredibly important - more important than the sport - but fail to register with fans.

And then there are times when the stories sound dull but turn out to be crackers that change the direction of sport, stories the public will care about for years to come.

So which kind of sports politics story is the increasingly poisonous scrap to become the next president of the International Cycling Union (UCI)?, external

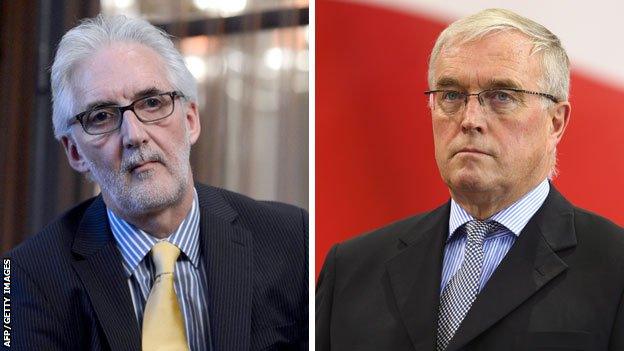

Is the fight between Irish incumbent Pat McQuaid and British challenger Brian Cookson of interest to anybody other than a few executive relocation companies in Geneva?

Will cycling be more popular with one of these men at the helm as opposed to the other? Would a Cookson-led UCI be "better" than McQuaid's version?

Before I suggest some answers, let's look at what is at stake, who the protagonists are and what they are proposing.

Why are they having this fight now?

The simple answer is that McQuaid's second four-year term as UCI president expires next month.

He was re-elected unopposed in 2009, having been the anointed successor of long-standing leader Hein Verbruggen in 2005.

Founded in 1900, the UCI is responsible for the administration and promotion of cycling's eight disciplines - BMX, cyclo-cross, indoor, mountain bike, para-cycling, road, track and trials - on the global stage.

From its Swiss headquarters, the UCI organises the sport's world championships, sets the calendar, decides the rules, runs training programmes, and works with the International Olympic Committee to put on the cycling events at the Games.

With 179 national federations as members, it also leads cycling's anti-doping efforts.

Until two months ago, it looked like a third term for McQuaid was in the bag, but Cookson decided to run against him, making this the most keenly-contested presidential campaign for more than a decade.

The election takes place on 27 September in Florence, in the middle of the sport's road world championships.

Who are the protagonists?

As things stand, this is a straight scrap between Cookson and McQuaid, although a late rule-change suggestion from Malaysia has thrown open the possibility of other candidates emerging from the shadows in the next four weeks.

Previously, candidates were supposed to declare their intentions to run 90 days before the vote. Prospective presidents were also supposed to be nominated by one member federation, typically their own national governing body.

But McQuaid has had some difficulty in securing such a nomination and his critics now accuse him of using his "insider" advantage to stretch the spirit of UCI law to guarantee his nomination, score political points and possibly even split his opposition's vote.

As Winston Churchill once said, politics is not a game, it is an earnest business.

That is something McQuaid has never needed explaining to him. A former professional cyclist, from one of Ireland's foremost cycling families, the 63-year-old Dubliner has been pulling his way up sport's slippery pole ever since his racing career finished.

Even before that, he was no stranger to controversy. He was banned from riding for Ireland in the 1976 Olympics when a photographer spotted him in a picture taken at a race in apartheid-era South Africa. He had entered using a false name to circumvent the boycott.

Trained as a teacher, McQuaid rose rapidly through the ranks of the Irish Cycling Federation and was soon winning friends at the UCI and beyond through his work as an organiser of races in China, Malaysia and the Philippines.

His accession to Verbruggen's throne in 2005 came as little surprise, particularly as his mentor stayed on as honorary president, and there was considerable continuity between the two regimes: the same focus on taking cycling to new markets and the same rows about the sport's appalling record on doping.

And while McQuaid can point to a number of significant successes during his tenure, it is for his combative style and legal tangles that he is perhaps best known. Some, however, will say you need to get your elbows out to get things done.

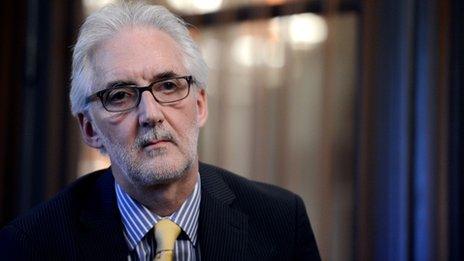

Cookson, on the other hand, is a natural diplomat and consensus politician.

An urban planner by trade, the 62-year-old from Lancashire made his name in sports administration by leading the team that effectively rescued the British Cycling Federation from financial ruin in 1996, turning it into an Olympic and Tour de France-dominating superpower.

A club cyclist, Cookson has emerged almost silently as the champion of all those determined to consign the McQuaid-Verbruggen years to the past.

His record in the relatively polite world of British cycling is beyond reproach, but he has only been at the UCI's top table, the management committee, since 2009. He has also, until relatively recently, been supportive of McQuaid's efforts to grow cycling and tackle its doping culture. That support has been emphatically withdrawn now.

What do they stand for?

On paper, as laid out in their manifestos, there is little between them. Both talk about growing the sport, particularly women's cycling, and doing more to promote it in the developing world.

Even on the election's most divisive topic, the UCI's record on anti-doping, their policies are similar.

Cycling disfigured by doping - Cookson

Both men say they want thorough investigations into the Lance Armstrong era, a period when the American and nearly all of his rivals were cheating, and both say they want to establish a more independent and robust anti-doping system to prevent that from happening again.

Where they differ, of course, is that McQuaid has a very chequered record to defend,, external while Cookson can point to a clean bill of health for British Cycling, external and some evidence of a more "independent" mind during his time on the UCI's management committee.

What this boils down to is a choice between a man who can justifiably say cycling has got cleaner on his watch and a man who can justifiably argue that it should have got cleaner quicker and with much smaller legal bills.

More of the same, or a clean break with the past? A classic choice in politics of any variety.

Where does their support come from?

Broadly speaking, McQuaid's support comes from the developing cycling nations in Africa, Asia and, to a lesser extent, South America. It is telling that his three nominations have come from Switzerland, where he lives, Morocco and Thailand.

The reason for this is more to do with the name-recognition and patronage potential of office, rather than any special work he has done to help cycling in these places, but that does not change the task facing Cookson, whose support comes from the more traditional cycling nations of Europe, North America and Oceania.

It should also be noted that McQuaid's Swiss nomination is the subject of a legal challenge in Zurich in three weeks' time, while the Irish federation withdrew its initial support under pressure from its own members.

But here is the central point: there are only 42 voters in this election.

The UCI's 179 national members are divided into five constituent confederations: Africa, Americas, Asia, Europe and Oceania. At confederation level, it is one member, one vote - but in Florence next month, the Africans will have seven votes; Americans nine; Asia nine; Europe 14; and Oceania three.

If Cookson can count on a European block-vote and backing from Australia, Canada and the US, he will get close to the 22 votes he needs: close, but not entirely there. He knows he needs to loosen McQuaid's grip on some of the smaller federations.

What are the key issues?

It is very simple: there are different issues for different voters.

In the developed cycling world, the big issue is undoubtedly cleaning up the mess from the Armstrong revelations, thereby convincing broadcasters and sponsors that the sport really has moved on, and can be trusted as a serious partner.

In the developing cycling world, where the subject of who really did win the 1999 Tour de France is of only passing interest, the main issues are making cycling more accessible, closing the gap to the big leagues and gaining more input on big decisions.

Why should we care?

This is a tough question to answer because recent evidence suggests the sport is doing fine despite the negative headlines about Armstrong, Operation Puerto, Erik Zabel and many, many more. You could infer that even an incompetent UCI does not really matter.

But I would argue cycling has been seriously held back by the perception of many that it is a dirty sport, seemingly incapable of sorting itself out.

Yes, TV viewing figures for the Tour, and other races, are encouraging. New sponsors have come in to replace those who left in anger.

Participation is up, the bike industry is healthy and millions of fans still come to watch the races on the roadside. We also seem to have a new generation of credible stars, putting in remarkable, but not super-human, performances.

But this ignores the careers that have been wasted, the dreams that have been dashed, the unnecessary legal bills, the public cynicism that will take years to diminish and the lost opportunities to be an even bigger, more popular, wealthier sport now.

Good governance matters in sport, in the same way it matters at your local council, children's school, pension fund or community hospital.

And if that is not reason enough for you to care, then just sit back and enjoy the theatre of what promises to be a much closer contest than this year's Tour.

- Published1 July 2013

- Published26 June 2013

- Published25 June 2013

- Published19 July 2013

- Published19 July 2013

- Published4 September 2014

- Published19 July 2013