Le Tour de Truth: Verbruggen fights to rescue his reputation

- Published

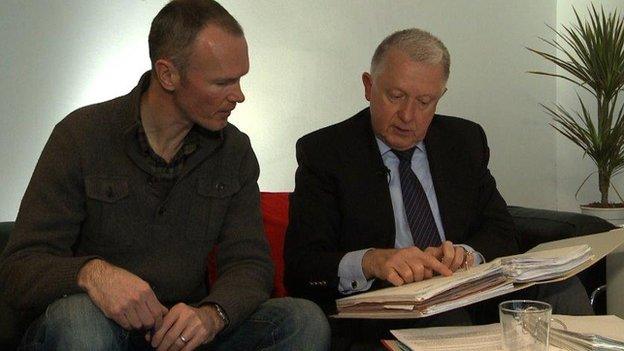

The world of international sports administration has thrown up some characters over the years, but few have come with as much baggage as Hein Verbruggen, quite literally, as he is carrying a leather holdall stuffed with binders and folders when we meet.

The former president of the International Cycling Union (UCI) has come to a TV production company's office in Geneva to give his first interview to the BBC since we reported allegations the UCI had taken money, external to get keirin into the Olympic velodrome.

The 72-year-old Dutchman has got an explanation for that in his bag, but that is not why we are meeting.

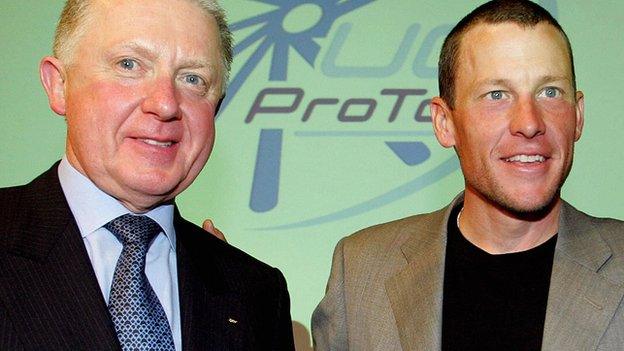

We are here to find out who is telling the truth: Lance Armstrong, the teller of perhaps the biggest lie ever told in professional sport, or Verbruggen, a man described by a contact of mine that morning as knowing "where all the bodies are buried".

It is almost a year since Armstrong told Oprah Winfrey at least some of the truth about what fuelled his seven Tour de France victories between 1999 and 2005.

Since then the fallen idol has largely been playing footsie with those seeking a bit more truth before they consider reducing his lifetime ban from most organised sport.

Last month, the Texan decided to float a bit more of his story, telling a British newspaper , externalhe tested positive for corticosteroids at the 1999 Tour, but asked Verbruggen "to come up with something" that would get him, and cycling, off the hook.

According to Armstrong, Verbruggen agreed, telling him to backdate a sick note and blame it on an ointment for saddle sores.

Verbruggen remembers it differently. He says there was no positive test, just an "adverse analytical finding" of which only a quarter progress to full-blown positive status.

He adds that it was the French anti-doping agency, not the UCI, that did the test, and it was the French who decided not to pursue it.

Just to emphasise the point, Verbruggen showed me emails from Armstrong and the rider's team boss at the time, Johan Bruyneel, from 2011 and 2012 that clearly state there was no positive test at the 1999 Tour, or anywhere else for that matter.

Verbruggen does admit he might have had a conversation with "somebody" about Armstrong's test at the time, but categorically denies telling the rider how to bury a positive.

The partially-remembered phone call does ring my alarm bells, but not quite as loudly as Armstrong does with his evolving narrative.

So three hours after the start of our interview, as Verbruggen bids me a cheery "bon voyage" at the airport, I am confused: have we perhaps got Hein wrong?

Before I try to answer that, let me go back to the beginning.

Our interview took place in a nondescript street squeezed between Geneva's lake and station. It was, by coincidence, around the corner from the UCI's old headquarters, a few rooms above another nondescript street.

Verbruggen denies Armstrong's claims of a doping 'cover-up'

"When I took over as president in 1991, I went to that office and found the secretary painting the fridge," Verbruggen recalls.

"I asked her why she was doing that, and she said it was because my predecessor refused to buy a new one."

The UCI was £1m in debt at the time, with offices in three cities and four full-time staff. This was the state of the organisation on the eve of cycling's move from endemic but low-level doping, to a state of rocket-fuelled chaos.

"Doping has been a cultural problem for cycling since the first races in the 1860s - society wanted athletes to do impossible things - but the drugs changed in the 1970s , externaland the real doping started," he explains.

Amphetamines came first, then steroids, and finally "the very unfortunate cherry on the cake", as Verbruggen describes it, EPO. , external

So effective is the blood-boosting hormone as a performance-enhancer for cyclists that you could be forgiven for thinking it was synthesised with that in mind - it wasn't (its main use is for treating anaemic patients with kidney problems) but the effect on the peloton amounted to the same thing.

In a matter of a few seasons, the abuse of EPO spread from the minority who will always cheat, to the majority who cheat if they feel they have no choice. It did not take long for everybody apart from the saints to be on it.

The first item on the popular charge sheet against Verbruggen is that he was either too incompetent to spot this, or so obsessed with the sport's image that he turned a blind eye to it, ignoring whistle-blowers like riders Jorg Jaksche , externaland Jesus Manzano, and Mapei team boss Giorgio Squinzi., external

At least one of Verbruggen's bulging binders deals with this accusation alone. Over the course of an hour, he showed me hand-written faxes, letters, speeches and press clippings that suggest he was at least talking about the problem., external

He had hoped some help might come in 1994 when the International Olympic Committee (IOC) funded an Italian study to find a test for EPO.

But when 1995 became 1996, and there was still no test, Verbruggen asked the doctor involved where it was because his sport was "out of control".

The doctor told him he had a test, but it needed a litre of urine. That is a lot of wee when you have been on a bike for six hours.

Verbruggen claims the UCI then funded its own research into an EPO test in Australia,, external Canada, France and Switzerland.

He had the documents to prove it, too, and sure enough, there was the UCI being thanked by anti-dopers who would later criticise the federation.

While cycling waited for a test, he introduced "health controls" to at least put some enforceable limits on the amount of blood manipulation the cheats could get away with.

For some this was a sensible move, for others it was a free pass as it told the dopers where the line in the sand was.

Verbruggen believes this is "hypocrisy", and says at least cycling did something. It is a point he repeats when he says the UCI recognised a new test for EPO , externalin 2000, three years before it had been peer-reviewed enough to satisfy the IOC and World Anti-Doping Agency (Wada).

"We stuck our necks out, we were the only ones, as usual," he says defiantly.

The untested test caught Danish rider Bo Hamburger in 2001, but the UCI would lose the case , externalat the Court of Arbitration for Sport.

The blood values of one of Hamburger's samples were just below the threshold needed for a positive. This would knock the UCI's confidence.

The defeat came in the same year the second of the great Armstrong-Verbruggen conspiracies is supposed to have happened.

Armstrong's samples from the Tour of Switzerland also threw up some suspicious blood values. Once more, Armstrong tells his team-mates that he has been caught, but friends in high places have made it go away.

Verbruggen emailed Armstrong in 2011 to say the rider's allegations were making his life a misery - Armstrong immediately denied the allegations

This claim would eventually lead to some of Armstrong's team-mates blowing the whistle loudly on Lance and Verbruggen, who reacted in his usual combative fashion.

"As president I could not go around speculating about riders - I would be in court the following day," he explains. "So I had to deal with positives, or negatives; that's all. There was no positive in 2001.

"By that stage I had nothing to do with the UCI's anti-doping team. Their door was the only one locked in the building, and there were seven or eight people of the highest integrity working there."

It was at this point of the interview I admit to losing track of all the steps his UCI was taking to deter cheats. Instead I find myself listing the number of rows he had with people who have eventually turned out to be telling the truth.

This, more than any other reason, is why his name is synonymous with cover-ups, while those who did actually cheat, riders like Tyler Hamilton and Floyd Landis, are viewed by some as heroes.

Verbruggen even got into a scrap with his former friend and IOC colleague Dick Pound., external This was unwise, he acknowledges that now, as Pound ran Wada, which saw cycling as the best proof that sport needed Wada.

The shame of it is that cycling needed Wada, too, something Verbruggen, who tells me he was considered as a candidate for Pound's job, should have realised.

Then there were the two donations the UCI took from Armstrong in 2002 and 2005. The first, for $25,000, was used to fund a drug-testing programme for junior racers, and the second, $100,000, was spent on a machine for analysing blood.

Oh, the irony.

Verbruggen holds his hand up to these mistakes too, but cannot help pointing out the documents that explain how above-board it was , externalat the time.

He also claims he was only ever paid travel and relocation expenses, never a salary, during his time in charge of cycling.

Verbruggen was a high-profile boss of world cycling's governing body for 14 years, during which time he increased the federation's global ambitions and turnover

He stepped down as UCI president in 2005, the same year Armstrong retired for the first time, an unfortunate coincidence, but the feuds and scandals continued during his successor Pat McQuaid's reign.

Verbruggen's culpability, real or otherwise, was not helped by the perception that his hand was still on the tiller, a perception he rejects, although he is the federation's honorary president.

What we do know is the UCI continued to catch cheats - Marco Pantani,, externalAlexander Vinokourov , externaland Alberto Contador to name just three - and implement anti-doping rules most sports have not even considered yet. That did not stop the bad press, though.

The UCI has a beautiful office , externalan hour's drive from Geneva in Aigle now. It is a model federation with 80 staff and a hi-tech training centre. Cycling is also more popular than ever, with races staged around the world.

But the sport is still hamstrung by its past and continues to punch below its weight commercially. This frustrates the businessman in Verbruggen as much as anything else.

He retires from his last big job in sport in March, the chairman of Olympic Broadcasting Services,, external but his will not be an easy retirement. He has been damaged too much by his association with Armstrong.

"There is a saying I like that says truth is the daughter of time," he says with an air of optimism tinged with regret.

Have we misjudged Hein? Possibly, but he has not exactly helped himself. And that is a shame for him and his sport.

- Published18 December 2013

- Published18 November 2013

- Published12 October 2012

- Published27 September 2013

- Published19 July 2013

- Published19 July 2013

- Published4 September 2014

- Published19 July 2013

- Published19 July 2016