Chris Froome: Why doesn't Britain love the Tour de France leader?

- Published

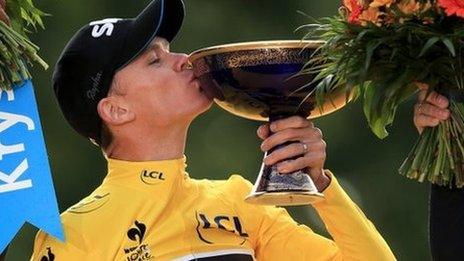

Chris Froome has dominated the early part of this year's Tour de France

Tour de France 2015 | |

|---|---|

Dates: 4-26 July | |

BBC coverage: Live text commentary of every stage online and radio commentary on BBC Radio 5 live sports extra or online from 14:45 BST |

There are days at the Tour de France when you would consider swapping non-vital organs for a bit of shade, but Chris Froome does not seem to mind when the tarmac gets sticky. Perhaps it is his African upbringing.

It could also have something to do with the two large shadows he toils under - one cast by a former team-mate, the other belonging to the Tour's most famous non-person.

The affable Froome's actual differences of opinion with Sir Bradley Wiggins have been a bit overstated: some professional jealousy here, a misunderstanding there and the occasional frustration at the constant scrutiny. This is regulation stuff for top sports teams.

But no amount of PR can hide the fact that the past and present leaders of Team Sky are very different personalities.

In his autobiography 'The Climb', Froome accused Wiggins of being "arrogant" during the 2012 Tour

The shame of it for Froome is that a large section of the viewing public, especially in the UK, has decided which of these two fascinating individuals they prefer, or can relate to more easily, and it is not the Kenya-born, South Africa-educated, Monaco-based 'Froomey' - it is the Belgium-born, half-Australian 'Wiggo'.

Froome's second sunlight-stealer is the Tour's self-styled Voldemort, the unnameable evil lurking in the woods, banished from the village because he cheated better, lied more aggressively and made more money than everybody else.

If it was bad timing for Froome to win the first Tour after Lance Armstrong (for it is he) finally got rumbled, it is cruel misfortune he should be leading the race again just as the American arrives to ride two stages of the race a day ahead for charity.

No wonder Armstrong, not usually one for long bouts of soul-searching, has seen fit to issue his second apology to Froome this year for passing on such a radioactive baton.

Lance Armstrong: In-depth interview

Unlike many other recent cycling champions - be it through their teams, coaches, doctors, former admiration for the man or some other link - Froome has no real connection to the man stripped of his record-breaking seven Tour wins.

The association is in people's heads. For some it is a nagging sense of deja vu, for others it is a refusal to be duped again and a few are still annoyed with themselves that they were duped in the first place.

That does not mean these feelings have no merit. The Armstrong era - and let us be clear here, he was one cheat among many - hurt a lot of people and it is entirely understandable for people to be suspicious, even cynical, for a long time to come. In fact, it is sensible.

Sensible but deeply frustrating if you are the focus of that suspicion.

Speaking at the finish of the Tour's 11th stage on Wednesday, Froome's team-mate Geraint Thomas, who has never ducked a question about doping, said: "It's a shame that is the way the sport is at the moment.

"You can understand why, in a way, because of the past, but you don't see that if a tennis player is doing really well, or a footballer is really good.

"It's just a shame that if you do a good performance on a bike that's the way it is. We've just got to keep doing what we do and doing it in the right way.

"I've got a clean conscience."

Froome has expressed the same sentiments. Many, many times.

There is a difference between Froome and Thomas, though, and it makes his story more like Armstrong's.

Tour de France: Thomas says Sky smashed it for Froome

Thomas, 29, has always been good. A star graduate of the British Cycling , externalsystem, the Welshman won the Junior Paris-Roubaix race at 17, a junior world title on the track at 18 and by 21 he was completing his first Tour de France.

He spent the next five years, like Wiggins, alternating between the road and the track, winning two Olympic gold medals in the process.

Concentrating on the road since 2012, Thomas has arguably been the most impressive rider at this year's Tour, with rival teams looking on enviously at the yellow-jersey contender Team Sky can afford to use as Froome's sherpa.

Froome, on the other hand, is cycling's great late bloomer, and in that regard he is similar to Armstrong's development as a Tour specialist from 1999 onwards.

For some, late-career or step-change improvements will always be suspicious. Where did that come from? Why have we never seen him do that before? What's changed?

We know the answer to those questions for Armstrong, although even there it is not as straightforward as some would like to think. Many of his rivals were up to the same tricks.

But for the 30-year-old Froome, this is undoubtedly his Achilles heel in the battle for universal approval.

Chris Froome's Tour de France career |

|---|

Wins his first Tour de France stage in 2012 at the top of La Planche des Belles Filles in the seventh stage. |

Finishes second in the 2012 Tour de France behind Bradley Wiggins, becoming the first two British riders to make the podium in its 109-year history. |

Wins the race the following year with a final time of 83 hours, 56 minutes and 40 seconds. |

Also becomes the first yellow jersey to prevail at the top of the Mont Ventoux since Eddy Merckx in 1970. |

For every coach or sports scientist who says the talent was always there, it just took the right support, a clean run of health, some race smarts and a bit more self-control at meal times to fully tap into the gifts he was born with, there will be a Twitter account to point out he was in the middle of the pack in mediocre races or hanging on to a motorbike at the Giro d'Italia, external when the likes of Thomas were mixing it with the best.

And that is before you even introduce the unflattering comparisons with cycling's pre-EPO generation champions Bernard Hinault, Laurent Fignon and Greg LeMond: a trio who were great from the outset.

This is the issue that most upsets Froome, his family and close friends, and it is why they have been making plans to provide more of the physiological data his critics demand, both in terms of where he is now but also where he was when he joined the International Cycling Union's World Cycling Centre team for developing nations in 2007. For what it is worth, the UCI coaches thought he was pretty special.

Whether that will be enough to convince his most ardent doubters is debatable. There is no agreed formula for what makes a champion - Mark Cavendish's lab numbers do not make much sense either but I have never heard anybody, anywhere, suggest he is doping.

Cycling fans have shown their support for Chris Froome during this year's Tour de France

All of this science, however, will make very little sense, or difference, to the vast majority of British fans who follow cycling for a few weeks every year, enjoy the spectacle and revel in our newly acquired competence in the event.

For most of them, 'Wiggo' was as good as it got. An Olympic track hero who got serious about the Tour and won it for Queen and country, while making gags and dropping British cultural references on a bemused French audience. Not that they seemed to mind; they liked him, too.

Froome can never be the first British Tour winner. He is also unlikely to ever have a news conference in stitches, stand on a podium in the Champs Elysees and say "we are about to draw the bingo numbers", play guitar at the post-show party at Sports Personality of the Year or share a hipster-friendly personal mix tape on Desert Island Discs.

But that does not mean he is boring or humourless, or that Wiggins is always a barrel of laughs.

Speak to any journalist, rider, race official or Team Sky staff member at this race and they will tell you that Froome is an engaging, friendly and unfailingly polite chap with a much underestimated warrior spirit who loves racing.

He is just not very British, is he? The British public knows it, he knows it, his team know it.

Tour de France 'everything' to Froome

When I asked a senior figure at Team Sky why their star does not ride the British Road Race Championship or Tour of Britain, external - for appearance's sake, if nothing else - he said Froome knows he will never be as popular as Wiggins and he does not mind. His job, and what he loves, is winning the Tour de France. Do that enough times and admiration, perhaps even affection, will come.

The irony is that culturally Froome is a lot more British than a great many of our rebadged sporting heroes.

His accent, manners and values are classic British ex-pat. Home for him is where he feels most comfortable and right now that is Monaco and South Africa, the country where he finished his education, started racing and met his Welsh-born wife.

But that does not make Froome South African, either. So perhaps we should just enjoy the performances that this British-influenced athlete is proud to put in with a union jack next to his name, whilst remembering that nationality is a slippery beast to pin down.

And that every top cyclist now must accept a level of scrutiny their predecessors avoided, with disastrous results.

- Published16 July 2015

- Published16 July 2015

- Published23 July 2015

- Published26 July 2015

- Published4 September 2014

- Published19 July 2013