Olympic Stadium: Final bill raises questions over West Ham deal

- Published

- comments

West Ham are due to move into their new home at the end of the 2015-16 season

Such was the inevitable focus on Mo Farah on Friday, it was easy to overlook the latest story regarding the scene of the British athlete's greatest triumph.

Just a few minutes before the double Olympic champion issued his statement, external denying the use of performance-enhancing drugs, the final bill for the reconstruction of the Olympic Stadium was revealed.

Converting it into the new home of Premier League side West Ham United will now cost £272m, meaning the overall spend will reach £702m for the 54,000-seater arena - a lot more expensive per spectator than the £798m lavished on the 90,000-capacity Wembley.

The announcement served as a reminder of two principal concerns that continue to hang over the stadium: the amount of public money used to make the venue suitable for football, and what some regard as a lack of transparency.

Certainly, the agreement that anchor tenants West Ham negotiated - to pay just £15m towards the conversion costs - looks more and more like the deal of the century.

The stadium's owners, the London Legacy Development Corporation (LLDC), admits the project is over-budget by around £35m.

Putting the largest cantilevered roof in the world on to a superstructure that had not been built to bear that kind of weight was far more complex and expensive than envisaged - the contract was announced initially at £155m, before rising to £189m in October.

Compare that to the £42m required to convert the City of Manchester stadium after the 2002 Commonwealth Games.

The new figures emphasise just how regrettable it is that the stadium was not originally designed for multi-purpose use - the original roof was not designed for long-term use and was too small to cover the retractable seats in 'football mode'. Had it been, the burden on the taxpayers would not perhaps be anywhere near as great.

The original plan was to convert the stadium into a 25,000-seat athletics facility after the Olympics. However, it later became apparent that having a Premier League football club would be far more financially viable, with Tottenham Hotspur and West Ham left to fight it out as the two main bidders.

Usain Bolt enjoyed winning gold medals at the 2012 Olympics Games in the stadium

The big problem was that London's 2012 bid team had promised the International Olympic Committee, external (IOC) that an athletics legacy would be maintained at the stadium.

Spurs wanted to remove the running track, which may have made more sense for the taxpayer but was seen as politically unacceptable, certainly by London 2012 chairman Lord Coe. To have backed the plan would have risked losing the support of Lamine Diack - the man he hopes to soon replace as president of the International Association of Athletics Associations., external

The fact Spurs wanted to redevelop the Crystal Palace stadium - and therefore leave an alternative athletics legacy in London - was not deemed good enough. But more of that later.

West Ham were, therefore, seen as the only option, leaving them in an incredibly strong bargaining position when it came to their financial contribution and meaning there was no choice but to compromise over usage. The stadium would have to be converted for both football and athletics.

But retractable seating does not come cheap. Not in a stadium that was not designed for it.

The LLDC points to the security gained by having an anchor tenant on a 99-year lease, and insists this will avoid the kind of white elephant that blight Olympic parks in former host cities such as Barcelona, Athens and Beijing.

It also says the Rugby World Cup matches this autumn and World Athletics Championships in 2017 are examples of the sort of world-class events the arena will be able to host, "part of a regeneration programme that will create an additional economic benefit to east London of well over £3bn".

Andy Silvester, campaign director at the Taxpayers' Alliance,, external is unimpressed. "The cost of renovating the stadium continues to spiral - much like every sports project the government gets involved in," he told me. "Taxpayers will be astounded that West Ham have been gifted a stunning new stadium for the same price that they paid for Andy Carroll.

"You can't blame the owners for taking advantage of this generous subsidy but such a cut-price deal simply isn't appropriate when you consider the extraordinary windfall coming the Premier League's way as a result of the new TV deal."

The LLDC points to the 10 annual community sports events the Olympic Stadium will host, a new floodlit community running track, a training and education centre and the 100,000 free West Ham tickets that Newham residents will be given each season.

West Ham paid the same amount for the Olympic Stadium as they did for striker Andy Carroll

But assuming Carroll and new coach Slaven Bilic help to keep West Ham in the Premier League, and the club can fill its new home, owners David Gold and David Sullivan can now look forward to a bright and very lucrative future.

With an iconic venue, the club is in an exceptional position to develop its brand, attract a new generation of fans and replicate the upward trajectory managed by Manchester City after they moved into their publicly-funded stadium. West Ham could become a real threat to the likes of Arsenal and Spurs, let alone smaller, more local rivals Charlton Athletic and Leyton Orient.

And, just like City, West Ham could also now be coveted by foreign investors - possibly from Qatar (who recently snapped up the Olympic village) or China (from where developers are pumping £1bn into London's Docklands).

Which brings us to the issue of transparency. If Gold and Sullivan do sell the club in the next few years for a big profit, the taxpayer will receive something back. But neither the club, the LLDC, nor the Mayor of London are prepared to tell us what proportion of any profit.

Equally, we are not allowed to know the rent West Ham must pay (it's been reported at £2m annually). That, we are told, is also subject to commercial confidentiality.

For many, given the vast amounts of public money going into the project, this secrecy is not good enough.

Meanwhile over in south London, all this is particularly hard to take.

If Spurs' bid had been accepted instead of West Ham's, the Crystal Palace National Sports Centre would be benefitting from a facelift that would have transformed its athletics stadium into a 25,000-seat facility. Instead, its indoor running track, a 25m swimming pool and the main stadium face demolition in the next few weeks as part of the Greater London Authority's, external (GLA) proposals to redevelop the site.

The Crystal Palace National Sports Centre faces demolition

John Powell MBE, chair of the Crystal Palace Sports Partnership Board, and an athletics coach at the site for the last 40 years, said: "There is widespread anger from clubs and the community about the top-down, centralised approach for funding hugely expensive projects that will benefit so few in the future, and harm wider grassroots access to sports and training to so many.

"West Ham are gifted a potentially world-class facility, while athletes training in south London will be forced to work out in the cruel British winter as Crystal Palace is likely to be razed to the ground. The current plans could be catastrophic for sport in London."

The GLA says the venue is underused and in poor condition. But many will struggle to understand Crystal Palace's plight, especially after figures this week from Sport England revealed an alarming drop in the numbers of adults participating in sport on a weekly basis, and the new Sports Minister Tracey Crouch demanded a replacement for the country's "severely outdated" sports strategy.

London Mayor Boris Johnson says the Olympic Stadium "will drive and sustain thousands of jobs [and] provides a genuine Olympic legacy for our city".

But as we approach its three-year anniversary, increasing numbers will be asking whether the hopes of a meaningful legacy from London 2012 have failed.

The stadium that became a symbol of those hopes now has a huge responsibility to provide some much-needed encouragement.

Could all this have been avoided?

Since publishing this article I've been contacted by architect Steve Lawrence who back in the '90s, worked on the very earliest concept plans for an Olympic stadium on behalf of the Stratford Development Partnership.

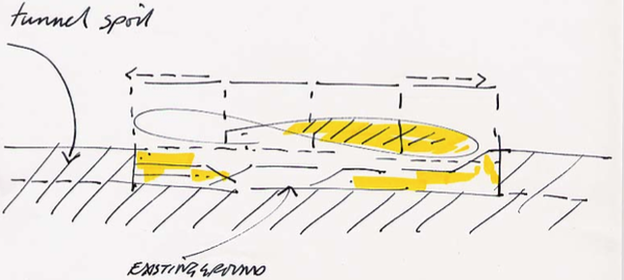

Lawrence claims hundreds of millions of pounds could have been saved if his ideas - widely distributed to London boroughs in 2001 - had been listened to.

"My plan was to construct the stadium in the six-metre high soil layer from the Channel Tunnel Rail Link so that the stadium bowl could be lowered post-Games as part of a conversion from athletics to football - with sight-lines for football designed in at the beginning," he says.

"In addition to the stadium becoming a football ground, the warm-up area next to it was going to be converted into a 20,000-seater athletics facility.

"The proposal was for West Ham and/or Tottenham Hotspur to be joint anchor tenants on a completely commercial basis, and we discussed the potential for converting the hockey arena for Leyton Orient, again to be let on a commercial basis."

"The problem was that the government sold 100 hectares of land for £12.5m as part of the Channel Tunnel Rail Link deal, and the new landowners were hostile to the idea of a football stadium on their extremely valuable land.

"So the stadium was eventually built on land that was purchased by compulsory purchase order and with the caveat that it would be athletics only."

It seems some people did think ahead after all. If only they had been listened to.

The plans Steve Lawrence submitted for the Olympic Stadium.

Drawings distributed by Steve Lawrence in 2001 with his ideas for the construction of an Olympic Stadium in London and how it would have been built above existing ground

- Published19 June 2015

- Published20 June 2015

- Published20 June 2015

- Published7 June 2019

- Published20 June 2016

- Published2 November 2018