Tom Daley wins Olympics diving bronze in typically dramatic fashion

- Published

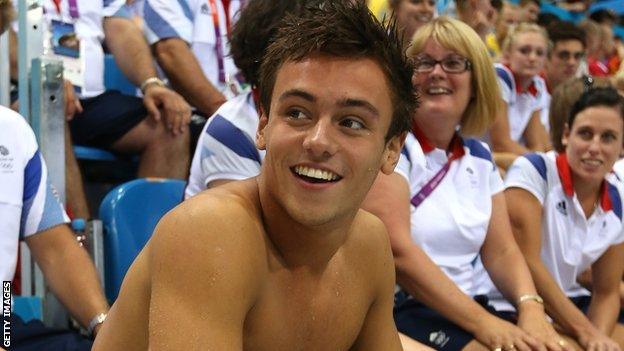

Tom Daley does not mind having his photo taken. Or he at least gives a good impression of somebody who does not mind having his photo taken.

But there is a time and place for a photo opportunity with him and it is pretty much anywhere, at any time - except when he is at work.

And when he climbed to the top of the 10m platform for his first dive on Saturday evening, he was very much at work. That means stop snapping, folks.

Did they listen? Do they ever listen when the photogenic teenager with the made-for-television back-story is about?

Olympic diving: Tom Daley profile

What happened next was both remarkable in terms of an Olympic diving competition and utterly in keeping with Daley's life.

Standing on his tiptoes, with his back to the pool, Daley took a deep breath and threw himself off the edge, twisting and turning as he fell at nearly 40 mph.

The crowd screamed, cameras flashed, water splashed. Too much water splashed.

Within moments the verdict was on the scoreboard, 75.60; not dreadful, but nowhere near good enough if Daley was going to win the medal that had been scripted ever since he went to the Beijing Olympics as the nation's most famous 14-year-old.

But for once the scoreboard was not the final word.

Daley, looking calm, called over his coach Andy Banks and told him to ask for a second chance as he was distracted by camera flashes on the way down.

"The environment has to be right," the 18-year-old explained afterwards.

"The home advantage cannot become a disadvantage because of all the photographers and fans trying to take pictures.

"It's tough when you are spinning around looking for the water and you see extra lights, it's very disorientating.

"But because of the experience I have now, I have learned to stick up for myself, so I asked the referee for a re-dive and the judges all agreed that the camera flashes had been distracting.

"It was an important re-dive as I would not have got the bronze without it."

Indeed, it was, but it was even more important that Daley took advantage of his "Mulligan"., external That he did, scoring a 91.80, should tell you everything you need to know about his ability to deal with pressure.

Because there can be few athletes at these Games who have performed under as much private and public pressure as Daley, and almost certainly no British athletes who have experienced anything like it.

With all due respect to the wonderful achievements of Mo Farah, Katherine Grainger and Laura Trott, none of those has been unable to go to the shops without causing a minor ruckus.

Daley has been front and back-page fodder ever since he emerged as a potential world-beater in 2007, aged just 13. He had already been embarrassing the best divers in Britain for almost three years but now he was going global.

Blessed with a winning smile, Daley was TV gold, particularly when the cameras followed him to his very normal Plymouth home and discovered what might have been a cautionary tale of the pushy parent. As it happened, the truth was even better.

Because Tom's relationship with his father Robert was not one of a too-competitive dad and the unwilling vessel of his sporting dreams, it was a simple story of love and pride.

Daley finds form to win bronze

Daley did not perform any miracles in Beijing but he did not need to, Britain was already hooked.

He did, however, produce the greatest ever performance by a British diver a year later in Rome, when he won a world title. When his winner's media conference was interrupted by Robert wanting to hug his son, well, his place in my mother's heart, for starters, was guaranteed forever.

Robert, at this stage, had been in remission for nearly three years after having 80% of a brain tumour removed. A year later, a second tumour appeared, and a year after that, he died.

This all happened to Tom in the full gaze of the British public.

But then Daley was used to making headlines for matters beyond the pool. In 2009, he was offered a place by the exclusive Plymouth College, external when it became known that he was being bullied at his state school.

If you thought that might encourage him to keep a low profile for a while, we were then reading about his GCSE photography project that involved him persuading supermodel Kate Moss to pose for a picture. His is a life that has always been about the lens.

Throughout all this, however, Daley continued to post results that suggested he might just pull off the Hollywood ending and win an Olympic gold in London. But, in true soap-opera fashion, this path was never smooth.

First, he was told to lose weight by the British diving team's Russian performance director, Alexei Evangulov. How could Tom, a nation's sweetheart, be too fat?

Then Evangulov went one step further to securing his status as a pantomime baddie by suggesting Daley was overdoing the publicity. The Chinese were not out opening supermarkets and tweeting to their thousands of followers.

And so we finally arrived at London 2012. No more media dramas, just sport.

Yeah, right.

Leading at the halfway stage of the 10m syncro final with partner Peter Waterfield, the pair put in a sloppy dive and never recovered. Fourth place is a horrible place to finish for a nation's big medal hope.

Back again 11 days later for his individual competition, Daley endured a torrid qualifying session, seeing one particularly splashy effort given 39.60 points. Was it all getting too much for him?

We got the answer to that on Saturday night, in front of 17,500 fans, most of whom were desperate to get a picture of Britain's most famous A-level student.

His bronze medal should not really sparkle that brightly in the context of a British team that has won 61 other medals, 28 of them gold, and three of those on the same day as his contribution.

But it will because nothing Daley does, or has to put up with, is like any other British athlete.

- Published11 August 2012

- Published11 August 2012

- Attribution

- Published11 August 2012

- Published11 August 2012

- Published10 August 2012

- Published30 July 2012

- Published12 August 2012