Boat Races 2015: Oxford, Cambridge & the fight for equality

- Published

The story of the women's boat race

2015 Boat Races |

|---|

Venue: The Tideway, River Thames, London Date: 11 April Time: Women 16:50 BST, Men 17:50 BST |

Coverage: Live on BBC One & BBC One HD from 16:15 BST, BBC Radio 5 live sports extra from 16:45 BST and streamed online |

Some said it was an anatomic impossibility. Others dressed it up in fishnet stockings and high heels. But one woman - Helena Morrissey, an investment firm boss and mother of nine - refused to allow the Women's Boat Race to be degraded any longer.

It may be a source of surprise that Saturday will see the 70th staging of the contest between Oxford and Cambridge.

Yet in the 87 years since they first took to the water, the women of the two august universities have never been permitted to race on the same course as the men and on the same day in front of a live television audience. Until this year.

Millions will follow worldwide and hundreds of thousands will line the four miles and 374 yards of the River Thames from Putney Bridge to Chiswick Bridge to watch a barrier being broken.

The route to this historic day has been arduous to the last, with the Oxford crew having to be rescued by a lifeboat from the choppy Thames waters just last week. But one moment of embarrassment matters little when you have endured almost a century of scorn.

Why is it happening now?

Helena Morrissey, pictured with Oxford's Anastasia Chitty and Henry Hoffstot of Cambridge, is behind the historic changes to the women's race

Money, quite simply.

Four years ago, Newton Investment Management offered the women's race a modest sponsorship package - the first in its history.

The presence of Natalie Redgrave, daughter of five-time Olympic gold medallist Sir Steve, in the winning Oxford boat, external that year ensured a decent dividend for the UK investment manager so, when the title sponsorship of the men's race became available after the 2011 event, Newton's parent company BNY Mellon made its move.

But there was a condition.

"We didn't just want a name on a shirt; we wanted to do something meaningful," Newton's chief executive Morrissey told the New York Times., external "Someone had to take the plunge."

Boat Races 2015: Meet Cambridge and Oxford's women crews

Her demand was unequivocal: move the women's race to the championship course on the Tideway alongside the men's and give both equal funding or the deal is off.

After initial reticence from the old boys of each institution, an agreement was reached on a five-year deal starting in 2012.

"I was staggered to realise that four years ago the women's race had absolutely no money in it," says Morrissey, a Cambridge graduate with no background in rowing, who has nine children.

"The women had to pay their own way and I found it shocking there was such a massive discrepancy between the men and women."

What was it like in the early days?

Cambridge have won 41 of the 69 races

The differences were stark and, like many traditions, the disparity was not rooted in reason either.

The first Women's Boat Race, in 1927, was held on the River Isis in Oxford. Heaven forbid they should compete side by side, though. Instead, the teams glided downstream separately so the judges could assess their "style and grace" before furiously grunting their way upstream against the clock.

Cracking the code of the Boat Races

This already curious spectacle was made more bizarre by the backdrop of irate men waving their fists and hollering disapprovingly from the towpath at these women sticking their oar in.

You see, apparently they were too delicate to negotiate the tides and bends of the river.

Indeed, as late as 1962, the captain of Selwyn College at Cambridge was moved to write to the university's women's boat club to chastise them for perpetrating something that was "a ghastly sight, an anatomical impossibility and physiologically dangerous".

That overlooked the fact it had developed into a keenly contested race over 1,000 yards on either the Cam or the Isis between 1935 and 1952.

'Fighters, trailblazers, but above all - women' | |

|---|---|

"It is remarkable how far we've come. The first race, in 1927, was staged after much discussion of whether they could wear shorts, or their more demure gym tunics. One of the Cambridge rowers had to sit on a stool in front of university staff, simulating the action of rowing, to ascertain which clothes best preserved her modesty." | |

What about more recently?

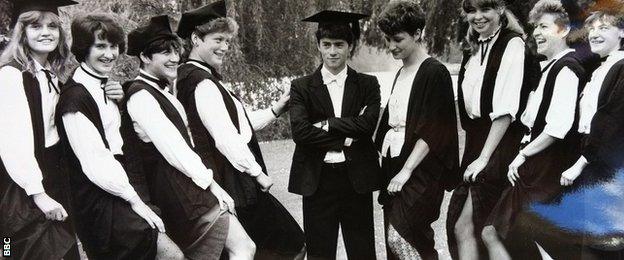

Oxford's 1985 reserve crew - in gowns, mortar boards and fishnet tights - pose with their male cox

A 12-year hiatus followed, a consequence of Oxford being banned from the river after slithering over a weir in training the day before the race and the financial burden of maintaining the crews.

However the contest was revived in 1964 and, by the mid-70s, had grown sufficiently to become part of the Henley Boat Races - where it came to be held over 2,000m - and accommodate reserve crews - Osiris for Oxford and Blondie for Cambridge.

Still, the gap between the haves and have nots remained pronounced.

"We had volunteer coaches, very little equipment, no boathouse… as president my main job was begging, borrowing and cajoling everything I could," says Alice Topley, who raced for Oxford in 1994.

"One day I managed to persuade a school to let us use their boathouse on the condition we would be careful but the cox dropped the keys to the bottom of the river."

One of her successors, Alison Gill, had similar issues. "We used to train out of one of the schools in Oxford and got changed in the car park," she says. "In my first race a seat on our boat broke because it was so old."

Then there was the tone of the coverage.

One newspaper headline in the mid-80s read "Trouble for the pretty maids all in a row", while Judith Behan - who competed for Oxford in 1985 - recalls her crew being asked to pose in towels for a photoshoot.

Has change been coming for a while?

Oxford, in the dark blue, won last year's race at Henley by a length

It seems to have been percolating over the past 15 years or so.

Oxford's Lisa Walker recalls an email arriving in 2000 mooting a move to the Tideway, while 2005 president Alex Cairns recounts talks taking place.

"A sponsor was interested and we thrashed out the logistics," she says. "But there was just not enough money on the table to make it happen - not from the women's point of view but from the men.

"I think they felt it was their race and their day and it was sacrosanct historically and they did not want it diluted. There was support from the teams and coaches but some of the alumni were against it, I suspect, because they doubted whether the crews were good enough."

So what about this year's race?

Doubts have been assuaged by three years of equal funding.

The women no longer have to part with something in the region of £2,000 of their own money each season to compete, with their kit, training camps and medical expenses now covered and their coaching requirements met by the appointment of three full-time members of staff to each team.

One of those was Oxford's feted Canadian head coach Christine Wilson, who has worked with the US Olympic team and was the first women to coach men at a major American university programme.

"Where we started and where we are now are light years apart," she says, tears gathering around her eyes.

"The Boat Race strips athletes down to the core of who they are. It plays out at a grim time of the year, the weather is brutal, so is the schedule, and it's dark for a lot of the time and that strips these women in a way that leaves them very vulnerable.

"There's this idea that women can't handle these things that demand strength and endurance but that's what we're designed for."

Both crews train twice a day, six days a week, with Wilson and assistant Natasha Townsend - who represented Britain at the Olympics in 2008 and 2012 - reporting at 05:30 BST to start the first session.

"I get really shocked by people who rowed with me who still ask 'are they going to row the same course' and I want to punch them in the face," says former GB women's eight stalwart Townsend. "People are going to be pretty shocked at the improvement.

"Christine jokes about how when we first met them they would shake our hands but not look us in the eye but they've all come out of their shell and now stick their shoulders back and hold their heads high.

"The Boat Race has done that to them."

- Published9 April 2015

- Published3 March 2015

- Published9 April 2015

- Published2 April 2015

- Published30 March 2014

- Published5 April 2019

- Published19 July 2016