Nelson Mandela: How sport helped to transform a nation

- Published

The image of Nelson Mandela presenting the Springbok captain Francois Pienaar with the Webb Ellis Cup in 1995 has become one of the most powerful in South Africa's history.

Mandela, who has died at the age of 95, understood how crucial sport would be in uniting a deeply divided nation.

"That was the moment all white South Africans' doubts about him evaporated and they accepted him as their legitimate leader," said John Carlin, a writer, broadcaster and friend to Mandela, whose book Playing the Enemy inspired the film Invictus.

Carlin, who was inspired to write Playing the Enemy by events leading up to that 1995 Rugby World Cup, added: "Other politicians will pay lip service to sport and understand theoretically its value to them - but they lack the political intelligence to exploit it the way Mandela did.

"He had the political genius to transform a symbol of division - the Springbok jersey - into an instrument of unity, which is why he is the greatest political leader of our time."

The decision to award the World Cup to South Africa was vehemently opposed by many black people in the country at the time, and not just on political grounds.

There were economic factors to consider as well.

In post-apartheid South Africa inflation and unemployment were high and 10 million people lived in shanty towns.

There was also a threat of terrorism from right-wing white militias who were extremely angry that a black man had taken power.

Carlin added: "Even for normal, clever politicians the news that South Africa was getting the World Cup would be motive for anxiety - or even despair - because the sport was so divisive.

"But Mandela saw an opportunity.

"He used to say, 'address people's hearts, not their brains', because he knew that was where he could make a more lasting impression."

It is clear that Mandela was influenced by the role sport played in keeping spirits high among his fellow inmates at Robben Island and, as a keen amateur boxer, he was always keeping himself fit.

Carlin fondly remembers one story he was told about Madiba, as he is known in South Africa.

"Every morning he would start doing laps of his cell until his good friend Walter Sisolo begged him to stop because the rest of his cellmates wanted to sleep," he said.

On another occasion, added Carlin, one of his lawyers went to visit him in Robben Island and Mandela, amazingly for a prisoner, was offered the possibility of eating some cake.

But he turned it down because he had lost a tennis match earlier in the week and he was intent on staying fit so he could get his revenge.

The success of the Springboks in 1995 and the way Mandela harnessed its effect helped to bring sport sharply into focus in South Africa.

Cape Town showed its ambition in bidding for the 2004 Olympics and by 1999, when Mandela stepped down as president, much work had been done in securing South Africa's right to host the football World Cup in 2010.

Carlin recalls that Mandela won the crucial vote after he paid a personal visit to see Jack Warner, the head of Concacaf, and the Trinidadian could not turn the great man down.

In 2003 South Africa, along with Zimbabwe and Kenya, would also host the cricket World Cup.

Carlin added: "Mandela was very influential behind the scenes.

"He knew how important rugby, football and cricket could be.

"What was remarkable [after 1995] was how the old professional white coaches would flood the townships and start teaching black children how to play cricket.

"And it is from that world that Makhaya Ntini emerged."

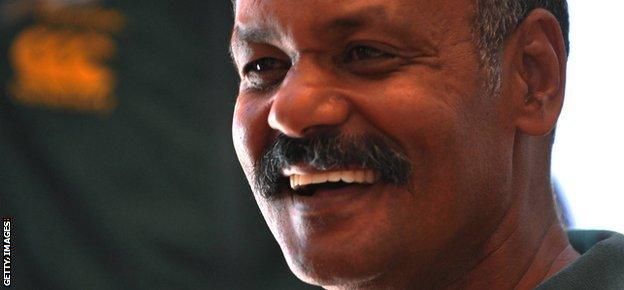

Makhaya Ntini - cricket

Makhaya Ntini's progression from township cattle-herder to Test cricketer is one of the greatest success stories in South African sport.

He grew up in a rural village just outside King William's Town, Eastern Cape, and went on to be educated at one of South Africa's most prestigious schools and play more than 100 Test matches for the Proteas.

His development as a cricketer coincided with Mandela's rise to power and it is clear that seeing a black man become president of South Africa provided the belief and opportunity for him to succeed.

Ntini said: "As black people, he made us understand that we could realise our dreams.

"We understood that it was a new era.

"Until then we'd never thought or dreamed about playing for our country - but after 1995 that all changed.

"We no longer focused on who we were standing next to, just on playing the same game for the same country."

As a hugely symbolic figure for young black people in South Africa, Ntini met Mandela several times during his career.

He added: "The first time I met him I was amazed that he knew so much about me.

"He called me by name and said he knew about my father, where he'd played, and that he knew the village where I came from.

"I thought to myself, 'He's been in prison for 27 years, so how could he possibly know all that?'

"Then you realise he was not just sitting there because he is a prisoner - but he was reading the papers and understanding what was going on outside."

In 2009, when Ntini made his 100th Test appearance against England at Centurion, he received a letter from Mandela.

It said: "What you have achieved goes beyond the number of matches you played; you have demonstrated, especially to the youth of our country, that everyone can rise above their circumstances and achieve success."

It is a concern to Ntini, 36, that young cricketers in townships today no longer have access to the same "opportunities" he had.

He says the number of coaches and scouts looking for talent in rural, deprived areas is no longer comparable to when Mandela was active in public life.

After the 1995 World Cup Khaya Majola and Dr Ali Bacher headed up South African cricket's newly formed national development programme.

They disagreed often but were responsible for making cricket the fastest-growing sport in black communities in South Africa.

As a result, the junior teams at national level became more representative - some age groups were 40% non-white - but despite the emergence of players at international level such as Hashim Amla, Ashwell Prince and Vernon Philander in the past few years, Ntini says progress lower down the chain has stalled.

He added: "There should have been more of us [black players playing for South Africa] but they are no longer doing now what they were doing then - I am always asking myself why they stopped.

"Khaya Majola and Ali Bacher insisted that coaches go out to rural areas to find players.

"They would then find them scholarships in a white school - that's exactly what happened to me.

"They took me out of my village and sent me to a white school [Dale College] where I had the opportunity to learn English and mix with different races.

"There are still lots of players out there but they have absolutely stopped looking for them.

"There have been only two [sic] black [using the South African designation], external Test cricketers for South Africa in the last 10 years - we should have had seven, eight, nine players."

There have actually been four, Monde Zondeki, Thami Tsolekile, Lonwabo Tsotsobe and Ntini himself [Mfuneko Ngam played the last of his three Tests in 2001], but none have made anywhere near the impact of the latter, who retired in 2010 with 390 Test wickets to his name at a healthy average of 28.

But more than the impressive statistics, Mandela recognised the part the bowler played in the history of South Africa and encouraged Ntini to use his profile to make a social impact.

Ntini, who now lives back in King William's Town, close to where he grew up, added: "He told me once, please go back home and tell the people from your village that you are a star because they will see what you have achieved and know that they can do it too.

"That conversation stays with me until today."

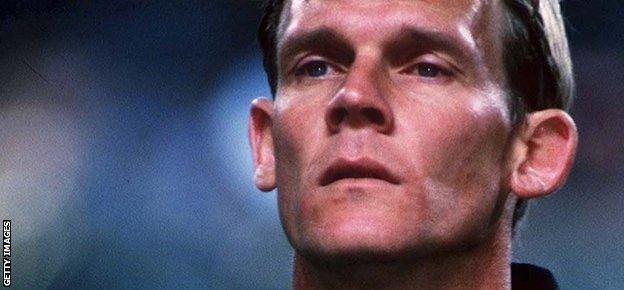

Peter de Villiers - rugby union

Peter De Villiers became one of the most controversial characters in South African sport during his spell in charge of the Springboks.

He says that many people thought it was "unthinkable" that a black man would be coaching the Springboks just 15 years after the country was re-admitted to international competition - but the 56-year-old has an unshakeable self-belief that was inspired by Mandela.

He said: "At the end of the World Cup final, I saw a great statesman standing in front of his country not presenting a trophy but representing the just rewards that people lost their lives for.

"That was brilliant to me, it showed us that nothing is a white man's thing in this world - nothing belongs to anybody.

"Nelson Mandela is somebody who inspires everybody whenever he does anything because it comes from the heart.

"He was the most genuine person that has ever been born.

"To me he was not a role model - a role model is something that can change - he was an icon who understood life better than anyone else.

"Mandela was not an ordinary man - he was an ordinary human being but an extraordinary man.

"He inspired me to be there for other people and to be honest and open in everything I did."

To say De Villiers did not always share Mandela's natural diplomatic skill during his time in charge of the Springboks is an understatement.

His outspoken approach often left him open to criticism, especially from sections of the media.

The case has been made that De Villiers's tenure as head coach was undermined from the moment he started the job, when Oregan Hoskins, the president of the South African Rugby Union, confirmed that his skin colour had helped him to get the job.

But the fact he was even considered for the post, let alone preferred to Heyneke Meyer, the current coach, shows how far he and South African rugby had come since the early 1990s.

De Villiers said: "Nobody had the right to call me a quota coach and whatever the white media said on a daily basis, not once did they say they I didn't know my job or I couldn't coach."

De Villiers, now 56, was a decent scrum-half in his playing day and represented Griquas and Boland provinces in the domestic leagues.

He admits to not being good enough to play at a higher level so coaching beckoned and, in 1992, the year the Springboks played their first match after re-admittance, De Villiers travelled to Europe to gain coaching experience.

He was brought into the South African rugby fraternity in 1998 when, then a coach at Western Province, he was named the country's under-19s coach.

At the junior World Cup in 1999 his side finished third and less than a decade later De Villiers had the first-team job.

De Villiers said: "It may have been unthinkable to other people but not to me.

"I told to myself if I want to compete I have to be the best that I can be.

"So to me, it was just rewards for the hard work that I put in.

"But I was inspired by what Mandela went through and how he went on to do the things he did.

"He was quite old when I became the coach but there was a special bond among us as the first black president and the first black coach of the Springboks.

"But he inspired me more by his silence than by what he said.

"He made me believe that if I was the best person I could be then I could make a difference and that I didn't need anyone's approval."

De Villiers is now the head coach at the University of Western Cape.

Neil Tovey - football

Nelson Mandela saw from his time on Robben Island how football gave hope to his fellow inmates.

The year he arrived in prison in 1964, football had just become a regular feature during exercise time.

And in a Fifa documentary called 90 minutes, Mandela said that "the game made us feel alive and triumphant despite the situation we found ourselves in".

Evidence of how highly Mandela placed football can be found on the day of his inauguration, in 1994, when he somehow found time to pay a visit to Soccer City in Johannesburg where South Africa were playing Zambia.

Neil Tovey, the Bafana Bafana captain, said: "He came on to the pitch at half-time and the game came to a standstill.

"It wasn't the normal 15 minutes' break. He greeted every single player on both sides.

"He knew that sport was a pivotal factor in him uniting the country - there was no doubt about it."

Fittingly, after trailing at half-time, South Africa went on to win 2-1.

Unlike rugby union, football had been a multi-racial sport in South Africa since 1978.

But the year after winning the Rugby World Cup it was football's year to shine.

In 1996 South Africa hosted their first major football tournament, the African Cup of Nations, after Kenya, the original choice to host the competition, withdrew for financial reasons.

The timing was ideal because it was clear during the mid-nineties that Fifa had its eyes on staging a World Cup in Africa.

Bafana Bafana beat some of the powerhouses of African football, including Ghana, en route to the final where they faced outsiders Tunisia.

Tovey added: "Mandela would sometimes call me ahead of big matches to give me some words of encouragement for the team.

"But the night of the final he came in to our team room and found time to greet every single player, child, waiter, wife, girlfriend and masseur in that room.

"I will never forget the humility of the man.

"As he left, he said 'my children, I leave the country in your hands'."

Mandela knew that for 90 minutes the only thing that mattered to his people was football.

More broadly, he knew how sport could help him achieve his chief aim - uniting a deeply divided country.

- Published6 December 2013

- Published6 December 2013

- Attribution

- Published6 December 2013

- Attribution

- Published5 December 2013

- Attribution

- Published5 December 2013

- Attribution

- Published5 December 2013