How elite sport can be a lonely, isolating and vulnerable place

- Published

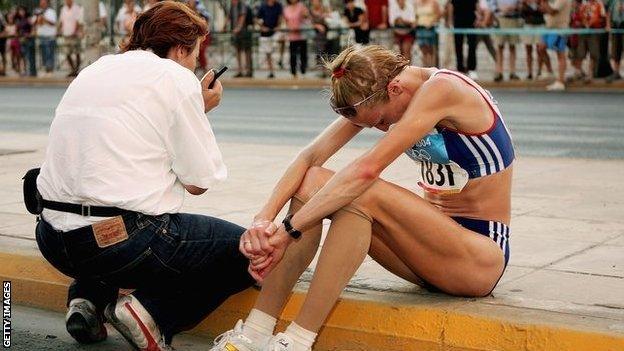

Paula Radcliffe felt isolated by the negative media reaction to her withdrawal from the 2004 Olympic marathon

Why does a top Premier League manager feel alone? How can you feel isolated, with no-one to turn to, in a bustling dressing room? Why can a jet-setting sporting lifestyle leave you feeling like a stranger in your own home?

Elite sport can appear a privileged profession, a chance to live out the childhood dreams of millions - and get paid for it.

But there is a darker side. For some the instability of life in the public spotlight can be as fraught as it is thrilling.

With the help of marathon world record holder Paula Radcliffe, former Aston Villa and Germany footballer Thomas Hitzlsperger, ex-England cricketer Steve Harmison and world-renowned sports psychologist Dr Steve Peters, BBC Sport looks at the issue of loneliness in sport.

It's tough at the top

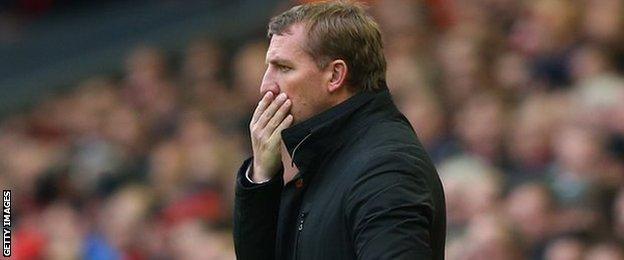

Liverpool manager Brendan Rodgers spends his day surrounded by players and coaching staff and making multi-million-pound decisions. Why, then, has he talked of the loneliness of command?, external

Brendan Rodgers succeeded Kenny Dalglish as Liverpool boss in June 2012

Peters works with Rodgers and also counts five-time world snooker champion Ronnie O'Sullivan, the England football team and the ultra-successful British Cycling squad among his clients past and present.

"Being in charge or having responsibility can be isolating," says Peters, author of the best-selling book The Chimp Paradox.

"People at the top of organisations can find themselves in isolation and that is a lonely and vulnerable place, especially as there is a lot of criticism that potentially goes with it.

"Alongside this can be a feeling of being assessed publicly, which can further add to a sense of isolation. It has parallels with other professions such as the police, doctors or teachers. Not having an acknowledgement of what you are going through can be very stressful and isolating."

The same feelings can afflict a sportsperson living a life where their every public move is forensically scrutinised.

"Some athletes get the feeling that the whole world is against them, especially when the media might be involved too," Peters notes. "They can feel that what is being written about them is unfair but is what people will believe. This may have a knock-on effect which can decrease self-esteem and create further feelings of being alone."

Desolate in the dressing room

The pressure of elite sport, as Peters points out, is not a problem for everyone - some people revel in it.

Former Aston Villa footballer Thomas Hitzlsperger |

|---|

"Of course I am not talking to my team-mates - we talk about football, we don't talk about private matters" |

For the majority of his career, that pursuit of success resonated with Hitzlsperger, who played for Aston Villa, West Ham, Everton, Stuttgart and Germany.

From making the Villa first team as a 19-year-old, to representing Germany at a World Cup and winning the Bundesliga with Stuttgart, football mostly brought happiness and a sense of inclusion.

But when personal issues started to take a more prominent role in his thoughts and motivations - earlier this year Hitzlsperger became the most prominent footballer to publicly reveal his homosexuality - the dressing room became a lonely place.

"Towards the end of my career when my private life became more and more important, I got that loneliness feeling," he said.

"There were times when I thought I would like to speak to someone but I can't. Of course I am not talking to my team-mates - we talk about football, we don't talk about private matters."

Isolation can lead to depression

Success is rarely a constant in sport. Failure, or the fear of it, is never far away.

Radcliffe experienced more highs and lows than most in her stellar career. After setting a marathon world record in 2003,, external which still stands, she arrived at the Athens Olympics the following year as favourite.

But the anticipated gold medal did not materialise, a combination of injury and stomach problems forcing her to drop out a few miles before the end. The negative media reaction left Radcliffe feeling isolated.

"After Athens was a difficult time for me because then it was really knowing who you could talk to," she said.

"That's when you learn who your best friends are and who you can open up to. You need to know they are not going to go to the media or abuse that trust of being able to share your inner thoughts, inner concerns and inner worries with them."

While Radcliffe wasn't affected to such lengths, psychologist Peters has experienced first-hand the link between the instability of a sportsperson's career and clinical depression.

Marathon world record holder Paula Radcliffe has experienced loneliness in her career

"I have had to treat a number of athletes for clinical depression resulting directly from the lifestyle that they are leading, their management of it and their own emotional responses," he says.

"There is little stable about the elite sports lifestyle and that, with potential isolation, can lead to depression."

A lonely life away - and back home

For former England fast bowler Harmison, the jet-setting lifestyle of a Test cricketer was part gift, part curse. Uncomfortable spending large periods away from home and his family responsibilities, the cricket field was a haven; his time off it something of a nightmare.

England fast bowler Steve Harmison struggled with loneliness due to cricket's demanding touring schedule

"Six and a half hours a day I was in a place I would not swap for the world - inside the boundary ropes in countries like India, Australia and the West Indies," he said. "For the other nine hours when I wasn't asleep, I was thinking 'I don't want to be here'."

Harmison is far from alone in struggling with the demands of travel. Two-time Olympic champion Victoria Pendleton - a disciple of Peters - detailed in her book Between the Lines how the loneliness of a Swiss training camp led to self-harm with a Swiss Army knife.

The feelings of isolation are not limited to life on the road. Peters has seen acute loneliness afflict elite athletes on their return home.

Steve Peters has worked with two-time Olympic champion Victoria Pendleton

The place they spent months pining for is suddenly the most isolated of the lot.

"Not unusually after returning from a lengthy trip abroad, some athletes feel that they don't belong at home and that they don't have any roots," he said.

"Their partners or friends have moved on and have got on with their life without them. I have met a number of athletes who report feeling like a stranger in their own home."

Retirement - the loneliest time of all

Perhaps the most dangerous time for an elite sportsperson is when the moment comes to call it a day. The void of retirement can be acute.

Four-time World Superbike champion Carl Fogarty recently outlined the isolation. "You feel lonely when it's gone," he said. "I missed the banter and the social side.

"When I retired I felt I had no direction in life. For three years I wanted to forget who I was. I was depressed because I could no longer do the thing I was good at."

That disorientation is something Harmison remembers. "Retirement is like walking out of a supermarket with all your bags and not knowing where your car is," he says.

"I quickly got some media work and I am still part of the game but it can be a struggle for cricketers. The Professional Cricketers' Association do some great stuff for players because from a mental point of view when it ends it can be quite tough. I miss the dressing room."

A Life Less Lonely is a BBC North project to explore the huge spectrum of loneliness in the UK on Friday, 12 December.

- Published6 May 2014