International Day of Happiness: Does sport make us happy?

- Published

- comments

International Day of Happiness: Does sport make you smile?

Does watching sport make us happy? That seems an easy one: when our lot win it does, when they lose it doesn't.

Except it's never that simple. Only one team in a division can win the title each season. Only one player can win a Grand Slam event or major. Only one captain can raise the Six Nations trophy this weekend. "Sport is about people who lose and lose and lose," the great American journalist Gay Talese, external once wrote. "They lose games, then they lose their jobs."

Losers. Hundreds of thousands of losers. When the United Nations decreed 20 March to be International Day of Happiness,, external you sense this is not quite the image they intended to promote.

But happiness is a strange thing, found in the most unexpected of places.

"I was at Headingley in 1995 when England lost to the West Indies by nine wickets in three and a half days," says Rob Evans, an otherwise rational 42-year-old man who has followed his national cricket team since childhood.

"On the last morning, with England eight wickets down and only 70-odd runs ahead, Peter Martin - a bowler who I can barely even think of as a Test bowler - hooked Ian Bishop for six.

"It landed two rows in front of me on an empty Western Terrace. I was ecstatic. I thought, 'A six! Wow, we're really giving this a go. We can win this!' It was one of my happiest moments at a Test match."

Happiness = low expectations

There is a reason for this, beyond hopeless delusion. Research carried out at Cambridge University by a professor of neuroscience named Wolfram Schultz indicates the amount of dopamine - the neurotransmitter that among other things helps control the brain's pleasure centres - we release is directly related to how much you were expecting an event to occur.

Peter Martin (blond hair), here celebrating the dismissal of West Indies skipper Richie Richardson for his maiden Test wicket, also hit Ian Bishop for six on his debut

Evans, like every other England supporter familiar with Peter Martin (Test average with bat: 8.84) had absolutely no expectation that he could smash Ian Bishop (who had taken 5-32 in the first innings and would break the jaw of England's best batsman, Robin Smith, a few Tests later) into the stands.

Hence, when it happened, a dramatic surge of dopamine. England were losing, horribly and obviously. But Evans could still feel wildly happy.

"We all know this intuitively about sport - that the happiest fans are those with the lowest expectations," says Eric Simons, long-suffering watcher and author of The Secret Life of Sports Fans.

"If you are behind in a game and then equalise at the death, that makes you far happier than being ahead and then drawing, even though ultimately it produces the same result.

"The best way to be as a fan is to have the maximum emotional investment in a team but the least expectation of success, because that's what rules the dopamine release."

'I don't care that we have no silverware'

Which bring us to Rochdale AFC, by many measures the least successful professional club in the country.

In the 108 years of their existence, the Dale are yet to win a single trophy. They have spent more consecutive seasons in the Football League's bottom division than any other club, have the lowest average position of any team continuously in the League and share with Hartlepool the dubious honour of having played the most seasons without ever reaching the top two tiers.

Chris Rodgers has been watching them for more than 25 years. His father Eric has been going to Spotland for half a century. Why?

"You feel part of something," says Chris. "Even when you're playing badly, it's the people you sit around. The football is secondary to what's going on in the stands around you.

Rochdale's Nathan Stanton celebrates with fans after their 2008 play-off semi-final win over Darlington - a rare moment of success for the club

"My single happiest moment as a Dale fan was Darlington, play-off semi-final second leg 2008, when David Perkins scored an absolute blinder to take it to penalties.

"We won the shoot-out, and that meant we were at Wembley, for the first time ever, in our centenary season. Stockport ended up beating us. No-one really cared that much. It was all about getting to Wembley."

Does it bother him that in more than 100 years of trying his team have never actually won anything?

"It doesn't bother me at all. It occasionally winds me up that Bury have won the FA Cup, because their fans like to point it out to us, but I don't care that we have no silverware," he says.

"We're never sure of a win. I went to watch Manchester United a few years ago when they played Wolves, and all their fans could talk about in the pub beforehand was how much they were going to win by.

"Who wants that? You want drama, you want competition. Not knowing the result before you even enter the stadium."

The higher the high, the lower the next low

Sometimes winning, much less make us happy, can actually make it worse.

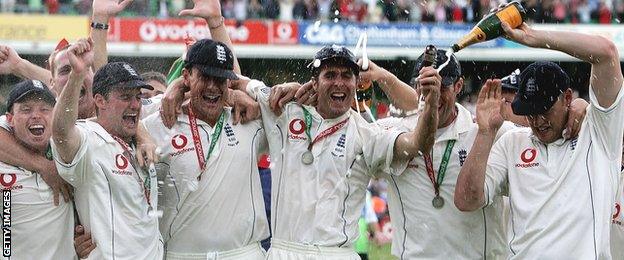

"The Ashes series win in 2005 was probably my highest point as an England fan," says Evans. "It's still the only time I've ever cried at the outcome of a sporting event.

England's 2005 Ashes win - their first in 18 years - was a heady time for players and supporters alike

"On the back of that win, and the bravado that came with it, my mate Rob and I decided: next Ashes tour down under, we're going. Forget the money, forget the time off work. England are really going to challenge. It'll be brilliant."

You can imagine the rest: a couple of thousand pounds down, watching through the night at home as England are hammered in the first two Tests, flying out to Australia with England ahead in the third, only to be told by a chipper Qantas pilot, descending towards Melbourne, that they had somehow contrived to lose that one too, and with it the series.

"The low was lower than any previous low," Evans says.

"All those previous disappointments and paranoias had been cast away by the win in 2005. Having to dust that old persona off again was horrible. And being in Australia made it so much harder. It's not a nice crowd to be in when they're battering you and you're playing rubbish cricket."

'Find meaning rather than happiness'

You could argue that being fed through the sporting mangle like this is actually good for us: a preparation for the more serious disappointments life will throw up, a source of empathy when others around us are also struggling emotionally.

In the frantic moment, watching sport can often be miserable - the suffocating tension, the complete lack of control over something we care so deeply about. In the long term, as so beautifully illustrated by Talese's famous profile of the retired baseball player Joe DiMaggio, it can bring a different sadness: at young heroes turned mortal and weak, at the passing of time and our own fading ambitions and dreams.

The death of Brazil's World Cup dream

But it is also a narrative around which to structure those years, a way of staying young through the deeds of others, an escape from the tedium of a humdrum world. And supporting one team or player, like membership of a religious or political group, creates both a distinct personal identity for us and camaraderie with otherwise complete strangers.

"Psychologists say it is more important in life to find significance or meaning than happiness," says Simons.

"So identifying yourself with a team, the idea of being part of a group, is very important. And you get that whether a team wins or loses. Losing together is a very powerful experience, and one that can help you much more in life than the shallow, superficial joy of winning."

Neither should we belittle it. It's certainly one way to deal with the failures and frustrations - pretend none of it matters compared to the Big Stuff like relationships, health or careers. But to do so is to be at odds with both nurture and nature.

"If you are looking at an image of someone's brain, the effect of taking cocaine or, as a Liverpool fan, watching your team beat Manchester City is essentially the same snapshot," says Simon.

"Sport does matter. It doesn't matter cosmically, but very little does. It matters to you, tremendously.

"It awakes all manner of powerful things, physiologically and neurologically. Things beyond your control.

"Respect that power a little more. If your team has lost horribly, legitimise that emotion. Of course you're sad, because this is what it is to be human - to be angry and frustrated over inconsequential things. Don't feel ashamed about your behaviour, because this is how we go through life."

Liverpool fans have had more than 30 major trophies to celebrate in the last 40 years

Sport makes us feel alive

How then to deal with that anger and frustration?

"England finally winning in Australia in 2011 and becoming the number one ranked Test team actually casts a shadow over my enjoyment of watching them now," says Evans.

"In the bad periods when you have no expectation of sporting glory, your pleasure is derived from watching the sport, from the social occasion - a nice day out with other like-minded individuals, and on the side you can celebrate England's small victories - a rapid partnership of 42 for the eighth wicket that briefly forces the opposition to remove one fielder from their five-man slip cordon.

Will England's rugby team live up to expectations and win the Six Nations title on Saturday?

"Even though I enjoyed Headingley 1995, I don't actually want to go back there - a half-empty ground, everyone laughing at how bad we are, Carl Hooper scoring 60 in 30 balls as they knock off 120 in 19 overs.

"But now being able to remember so clearly it being so much better so recently actually makes it worse. I watch this current squad - some of who were part of those successes - being utterly unable to recreate it. I can recreate in my mind how good it felt, but the players can't make it happen."

When Tennyson, external told us in 1849 how it was better to have loved and lost than never to have loved at all, the first rugby union international was still 22 years away. The first England-Australia Test was another five years on; the Football League would not come into existence until four years before Alfred popped his poet's clogs.

Yet the melancholic old boy summarised it rather well for the sporting supporters to come.

Who wants to go through life insulated from emotion? Sport - the winning, the losing, the hoping, the hating, the tension and the despair and the very occasional ecstatic moment - opens us up to feeling alive. And if a deflected long-range shot against Darlington or Peter Martin slogging a six finishes up as one of our happiest memories, so be it.

- Published19 March 2015

- Published19 March 2015

- Published13 March 2015

- Published24 March 2014

- Published17 March 2015

- Published1 February 2015

- Published14 September 2016

- Published15 February 2019