Sport 2050: Beneath the dome - how cricket could look due to climate change

- Published

Cricket has been warned. The sport will be one of the worst affected by climate change if nothing is done.

So what does cricket in 2050 look like?

BBC Sport has imagined a version of the future where intelligent 'bio-domes' create an atmosphere like nothing we have seen... yet.

Before it opened earlier this month, the Melbourne "Dome of Cricket" was hailed as the saviour of Test cricket in Australia.

But just days after the first ball was hit, it was dubbed a "real problem" for the sport, according to Australia captain Bobby Iluka.

The controversial dome - costing A$3bn [£1.65bn] - was designed to not only protect players and fans from extreme heat and provide a controlled environment, but also reduce the rising number of days lost to wildfire pollution.

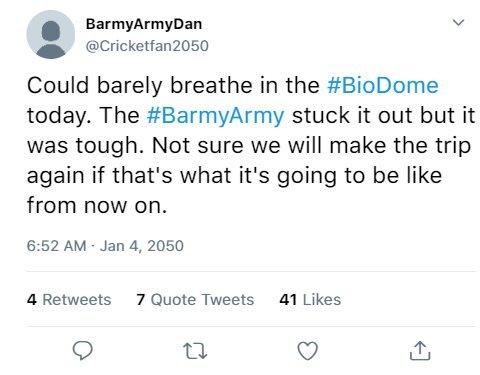

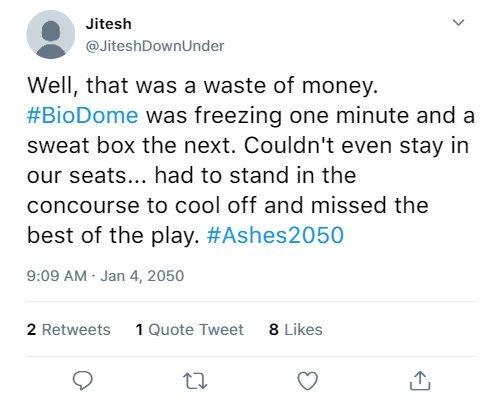

But it has already come in for criticism from players and fans alike both for its impact on the game, and technical difficulties with the climate-control system caused by the size of crowds varying dramatically.

Sport 2050: How does extreme heat affect athletes?

So what happened in the dome?

Following the drawn fourth Ashes Test with England, Iluka became the highest-profile critic so far, insisting it was "impossible" to prepare for the conditions inside the dome.

"On day one, the first session with 100,000 people inside, it was almost hotter and more humid than outside and unpleasant to play in, let alone watch. I saw many fans had resorted to leaving," Iluka said.

"Then, by the afternoon session, changes had clearly been made but the temperature dropped rapidly.

"These aren't good conditions for any sport or athlete but batting out there, it was impossible to predict what the ball would do from one session to the next - we got lucky basically."

When asked if he would want to play at the dome again, Iluka was typically blunt: "No, we've got a real problem here.

"We have moved the Ashes later in the summer (losing the Boxing Day/New Year's Day element that has been such a big part of cricket here) and although that has helped in other areas without domes, I am not sure cricket indoors is the future... at least not yet."

Beneath the dome: Cricket faces a challenging future by the middle of the century

Reaction - what did people make of the dome?

By 2050 cricket has already experimented with making Test matches six days, rather than the current five, to accommodate more intervals and reduce the length of sessions.

But Iluka dismissed that concept as "too long" and said it "asks too much of players and fans alike".

Instead, he suggested: "I would favour a complete reversal; let's make cricket a winter sport. I know there would be calendar conflicts with the European season but it's the best of a bad bunch of solutions.

"Cricket is a sport so in touch with its conditions that playing indoors feels wrong."

Fans too were not amused. Some were vocal about how they were so uncomfortable they left the dome and missed wickets as a result, although others were impressed by the set-up.

The dome, which uses solar panels to power itself, has been defended by its private owners, who have built indoor sports infrastructure in countries across the world to combat adverse climates.

They describe the technology as cutting edge, but did admit that the tech is a work in progress and would have to be adapted as they go along.

However, they insisted that in the face of more severe climate impacts and wildfires, their stadiums are the future of not just cricket but maybe more sports around the world.

A wildlife sanctuary? Campaigners want to see the dome repurposed

Eva Bakker, captain of the Netherlands women's team who played at a recent Test event, said that when the stadium was less full it was often almost too cold. She also pointed out that the pitch just didn't deteriorate in a natural way.

"Our understanding of cricketing decisions as a fielding side, bowler or batsman have to change dramatically when playing indoors. Test cricket is facing a real challenge in these hotter countries," Bakker said.

"The game has exploded in my home country as a summer sport and in other less familiar areas like Scandinavia but for its traditional heartlands like Australia, India and so on, I don't know what the answer is in the face of rising temperatures."

One group of environmentalist sports fans, WIDES (Western Australia Defending Earth & Sport), has now mounted a campaign against the future use of the dome and has enlisted the backing of celebrities to turn into it a rescue centre for animals affected by the wildfires.

Organiser Lou Olsen told BBC Sport: "I love and want to save Test cricket but this hasn't worked. It's most important we save the animals - let's turn it into something good and use it as a sanctuary/bio-dome."

Why have we chosen this story? - The expert's view

Kate Sambrook - Priestley International Centre for Climate

Of all the major sports played on pitches, cricket will be hardest hit by climate change - regardless of whether it is being played in England, Australia, India or South Africa.

Extreme heat in particular is a major issue for those playing the game as it not only affects the condition of the pitch but also impairs the performance of athletes and poses significant risks to their health.

Combined with high levels of humidity, the risk of heat illness - characterised by nausea, dizziness, vomiting and faintness, and even, rarely, leading to death - is progressively greater as the environment becomes hotter and more humid.

But this isn't just something that players will have to endure in the future - extreme heat is affecting international cricket here and now.

Cricket will have to evolve and develop - Root

During the Sydney Ashes Test in January 2018, England captain Joe Root was taken to hospital suffering from dehydration and viral gastroenteritis as air temperatures hit 42°C.

A heat tracker in the middle of the ground showed a reading of 57.6°C.

While cricket has always had to endure hot spells in the past, higher concentrations of greenhouse gases in our atmosphere will increase the intensity of summer heat and pose enormous risks to the longevity of the game as we know it.

Air pollution from wildfires will become more common

Matt McGrath is the environment correspondent for BBC News

While heat stress is a major threat to future sports events, air quality is another factor that can have a negative impact on competitors.

We've seen examples in recent years of athletes being impacted by smoky air from wildfires in Australia and the US.

Climate change is likely to make this experience more common.

If carbon emissions continue on a very high path, then by the middle of this century we could be seeing 35% more days with a high danger of wildfire across the world.

This presents a danger not just to places we currently associate with fires such as California, parts of Australia and southern Europe.

Smoke from fires can rise up to 23km into the atmosphere and be carried across continents on the winds.

As well as smoke, these fires produce huge amounts of fine, particulate matter. These tiny fragments - 30 times smaller than the width of a human hair - can penetrate deep into the lungs and into the blood stream, exacerbating asthma and leading to a spike in heart attacks.

The dry conditions and water shortages that will produce the fire-weather days of the future will also impact the sporting arenas we know and love.

In many cities, attending a sporting event could become very unpleasant because of an aspect of climate change called the heat island effect.

All the roads and buildings in a city absorb and re-emit much more heat from the sun than a rural landscape.

This heat island effect can be up to 5C, which could make attending a sports stadium in a big city in hot regions of the world uncomfortable at best.

An important thing to remember about climate change is that it is set to make a difference to the number of warm days we experience all over the world.

The recent run of record-breaking warm summers that have been experienced in the US, Europe, and Asia will likely become much more common.

Research shows that 50% of summers in the 2030s will be warmer than the hottest ones of the past 40 years.

By 2050, every summer will likely be warmer than what we've experienced recently.