NFL: The Miami Dolphins team of 'misfits' who won the Super Bowl undefeated

- Published

- comments

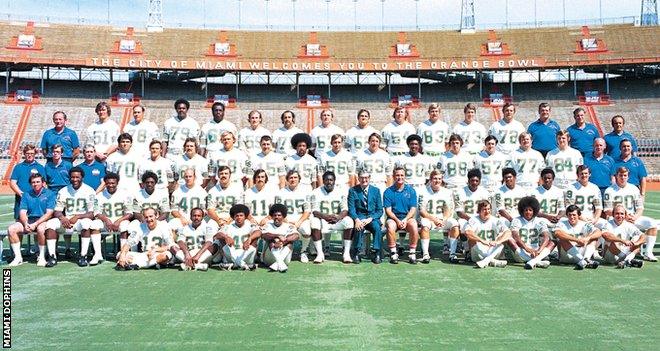

The Miami Dolphins began the 1972 campaign with the previous season's disappointment at the front of their minds

Jim Langer lay on his bed at the Waldorf Astoria on a chilly New York morning in December 1972, waiting for the Miami Dolphins team bus to leave for Yankee Stadium.

"You know we haven't lost yet?" quizzed room-mate Bob Kuechenberg. "Maybe it wouldn't be such a bad thing if we lost a game once…. So we don't have that jinx on us."

Langer and Kuechenberg were good friends and had both been part of the Dolphins squad that suffered a gut-wrenching defeat by the Dallas Cowboys in the Super Bowl 11 months earlier.

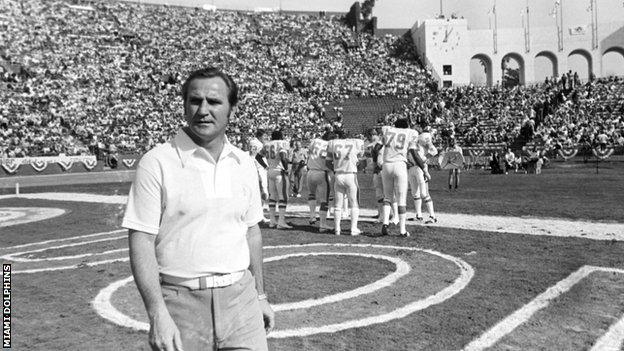

But this particular mid-morning chat in the Big Apple was by no means serious. The Dolphins had already secured a play-off spot by winning their opening 12 matches and coach Don Shula, himself the victim of two Super Bowl losses, would never allow his side's standards to slip.

Later that afternoon, the New York Giants became yet another scalp in an unprecedented perfect season.

Shula's invincible Dolphins would go on to win the Super Bowl that year with an undefeated 17-0 record. It had never been achieved before and - as the National Football League enters its 100th season - has never been achieved since.

"Man, it's been a long time," recalls Langer. "Nobody thought we would be talking about this 40-something years later.

"I mean, hell, I just lost Bob earlier this year. I roomed with him for 10 years. That was a very special team. It became a family."

The '72 Dolphins' legacy has outlasted some of the players that made it possible - Kuechenberg died aged 71 in January and Hall of Famer Nick Buoniconti passed away in July at the age of 78 - while a selection of those who remain still raise a toast together when the last undefeated team loses each season.

Their record as the only Super Bowl champions to record a perfect NFL season lives on. This is the story of how a bunch of "cast-offs" who were working part time, with a quarterback signed for $100, rallied together to achieve sporting greatness.

Shula holds the NFL record for most career wins as a head coach, with 347

The season before coach Shula's arrival in 1970 the Dolphins finished the campaign with just three victories and 11 defeats. They'd won only four games a year on average in the franchise's short history prior to that.

Paul Warfield, then with the Cleveland Browns, says Miami were regarded as a "misfit, loser, ragtag" organisation whose players were "not disciplined" and "not committed".

Everything would change.

Former Baltimore boss Shula sprung a shock trade for wide receiver Warfield and began cobbling together the "misfits" who had been cut or released by other teams.

"We were a bunch of cast-offs," laughs Langer, himself signed as a free agent from the Browns.

"It was hard when Shula first got there. He put 22 new players on the roster and a lot of the older players just didn't buy into that kind of work ethic.

"It literally became your life. But that's what it takes, that is just how Don Shula wanted to practise."

In his second season in charge Shula guided the Dolphins to the first Super Bowl appearance in their history, but on an unusually cold night in New Orleans in January 1972 they were beaten by the Dallas Cowboys. Shula and his players were devastated.

"We were a young team that was inexperienced at that level," remembers Warfield, 76. "We were happy with being there. We failed to understand the responsibility that, once you get there, the thing that matters is to win the game."

Such was the Dolphins' desire to avenge their loss that players would begin meeting each morning during the summer at the University of Miami to lift weights and train, despite having to hold down regular jobs.

Safety Dick Anderson sometimes made more from his sales job than he did pro football, while captain Buoniconti was a lawyer who had passed the Florida Bar.

In mid-July, Shula sent his squad for a gruelling six-week pre-season training camp in Boca Raton with the message: "Gentlemen, just take one thing from last year - nobody ever remembers who was number two in the Super Bowl."

The camp involved four sessions a day, just one night off a week and a curfew not to be missed.

"That certainly created a lot more camaraderie," says Anderson, now 73.

"Around 7.30/8pm at night we'd all go out and drink beer for an hour or two and then race to get back because we got fined if we didn't."

Money was not the driving factor for most players. They could expect to pick up around $15,000 a season (£12,200 at the current exchange rate), albeit about the same again if they earned a championship ring. It was about "playing the game and being part of a team". And winning the Super Bowl.

"It was pride, it was a football game, it was sport," Anderson says. "We were together more often, we were friends."

Anderson was part of the Dolphins' legendary "No-Name Defence" - so called because of their more modest profile - coached by defensive coordinator Bill Arnsparger. Monte Clark was responsible for shaping the offensive line and before every game would tell his charges "we are going to be the best in the business".

"We never questioned a single defence that Bill Arnsparger called," remembers Anderson, who spent his entire NFL career with the Dolphins.

"We had players who did not make mistakes. Our coaches really set the tone for our ability to execute and not make mental errors."

By the time they lined up against Kansas City Chiefs on 17 September for the first game of the 1972 season, the Miami Dolphins were ready to make another charge for the title.

"Shula was the most intense man I have ever been around," says Langer, 71. "He believed in it to his very soul and he worked as hard as we did in what he needed to do to get us ready to play.

"I never had any doubts. At the time when I crossed that line it was the most important thing in my life. I have been married 51 years, and my family is very important to me, but I knew the best way to look after them was to do the best I could for this football team.

"Shula was an amazing individual and we bought into his programme. We out-worked everybody and it paid off. We went into a game thinking: 'We should win this game - if we play the way we're supposed to we should beat this team.'"

Week after week the wins kept coming. Kansas, Houston, Minnesota, New York Jets. And then suddenly, crisis. Quarterback Bob Griese, named the NFL's Most Valuable Player a season earlier, suffered a broken leg and dislocated ankle against the San Diego Chargers.

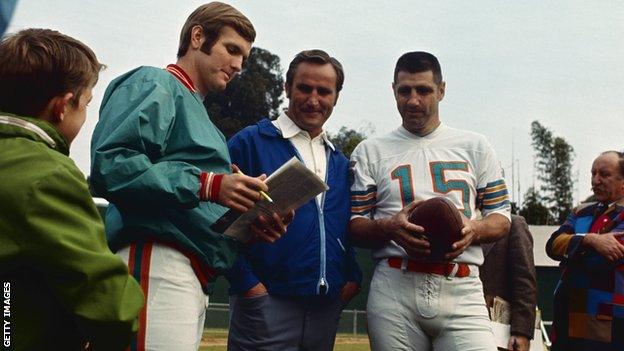

Shula turned to Earl Morrall, a 38-year-old claimed on waivers for $100 in April and nicknamed "Old Man" by his team-mates.

Shula (centre) with quarterbacks Bob Griese (left) and Earl Morrall (right) during a practice session

The veteran slipped in seamlessly, helping the Dolphins continue to grind out victories as Larry Csonka and Mercury Morris both rushed for 1,000 yards and Warfield led the receivers with 606 yards.

"We had two or three games I thought we easily could have lost," says Langer. "Champions don't beat themselves. If they have some adversity they are going to fight back.

"That's what the Dolphins did, many times. We could have given up and thought 'it's just one loss, no big deal', but we didn't want to lose. Don didn't like that!"

And so the wins continued. Shula's side, without their star quarterback, completed a 14-0 regular season.

"It really was one game at a time, you didn't want to look two or three weeks down at who we were going to play or what we were going to do," recalls Anderson. "We were really able to deal with one team and then forget about that and go to the next one."

As well as their machine-like defence and well-oiled offence, Miami used the Florida climate to their advantage. Langer says the heat rising off their Poly-Turf Orange Bowl field could reach 140 degrees Fahrenheit - that's 60 degrees Celsius - during day games.

"I played at 260lbs and I was 10% body fat," says Langer. "Six feet above the turf we were breathing in air at 120 degrees (49C). We'd lose 25lb in a football game.

"We'd get into games late in the season and teams that had been up north weren't used to that kind of heat.

"It became an advantage to us to understand 'hey, if we can conquer this heat and keep our performance level high enough we'll simply bury other teams on that virtue alone'. They just couldn't keep up with us."

Cleveland fell first in the play-offs before the Dolphins dispatched Pittsburgh Steelers on New Year's Eve, as quarterback Griese returned off the bench to help seal a narrow 21-17 victory.

The city of Miami was once again brimming with excitement - the players had been mobbed at the airport after beating Kansas in the play-offs on Christmas Day a year earlier - and the Dolphins were keen to soak it up. There were some unique opportunities for entertainment.

"I remember going out onto a British warship to have a pint with the sailors," says Langer, who'd befriended an Irish tug boat operator.

"It was a blast. It was a lot more relaxed off the field. After games the fans would have a food table set up - we'd go out, have lunch and a few beers. You'd go to the grocery store like anybody else, walk around town like anybody else."

And so to the Super Bowl.

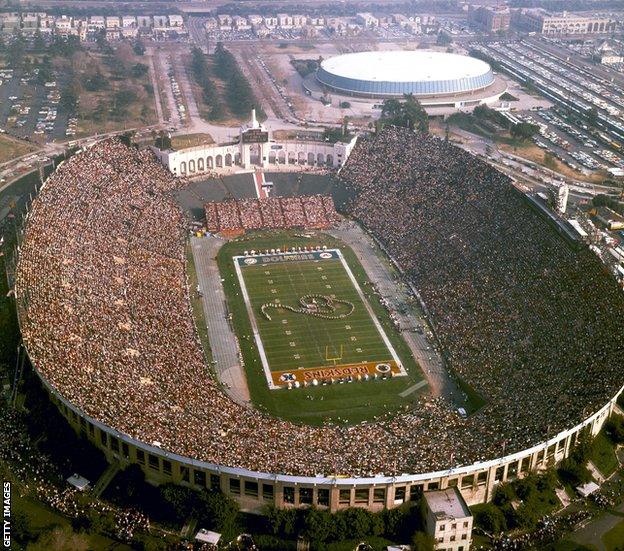

Super Bowl VII in January 1973 drew a crowd of 90,182 to the Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum

The Dolphins arrived in California a week before the match, opting to train at a local community college rather than the proposed LA Rams facility as they feared being spied on by their opponents.

Come game day, Miami headed to Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum on a 16-match winning streak, but it was the Washington Redskins who were touted as favourites, having supposedly seen off tougher opposition en route.

"We kind of took offence to that," says Warfield.

"This was the game we had been planning for since we lost the Super Bowl the year before. Everything was on the line. We were physically ready in every respect to accomplish what we failed to accomplish the year before."

After the cold snap in New Orleans 12 months earlier, 14 January 1973 proved to be the warmest Super Bowl on record. In balmy conditions hitting 29C, the Dolphins edged to a 7-0 lead in the first quarter after Howard Twilley caught Griese's 28-yard pass for a touchdown and Garo Yepremian kicked an extra point.

By the halfway stage, on the back of a dominant defensive display, Shula's side had doubled their advantage thanks to running back Jim Kiick's score and another point from the boot of Yepremian.

The half-time entertainment, a high school marching band, offered some light relief ahead of what was an intense and potentially season-wrecking final two quarters.

The cagey encounter remained 14-0 with little over two minutes left on the clock. And then, disaster for the Dolphins.

Yepremian's attempted field goal was blocked and chaos ensued as the kicker grabbed the loose ball, fluffed a pass and instead palmed it up in the air for Redskins cornerback Mike Bass to snatch and run 49 yards for a touchdown.

"Yeah, that nearly cost us the game," says Langer. "Garo was just trying to make the best play he could. He was a great kicker for us, very instrumental.

"It got a bit tense on the sideline. It gave us a scare, focused us again."

Fortunately for Yepremian, Shula and Miami it was just a scare. The Dolphins managed to blunt the Redskins' final attack and see out the final few seconds. They won the game 14-7.

"I'm in the huddle on the field at the Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum and the clock is winding down," recalls Warfield, one of seven players from that Dolphins team, along with coach Shula, to be named in the Hall of Fame.

"'Ten, nine, eight, seven…' we don't want to leave that huddle. It goes down to 'one, zero…' I look up and the scoreboard is flashing: 'THE DOLPHINS ARE SUPER!'"

Shula was hoisted on to his players' shoulders, a mixture of relief and jubilation etched across his face. "Nobody ever remembers who was number two," he'd told them after defeat the previous year. Now his Dolphins had done it: Super Bowl champions, the perfect season, 17-0.

"We came into the locker room and someone had written on the blackboard 'Perfect Season'," says Langer. "That's when it really dawned on everybody."

Anderson remembers: "Winning the Super Bowl was the big deal. That was our goal, that was what was important. We just happened to win all the games to do it."

As for Warfield, that "misfit, loser, ragtag" organisation he'd joined two years earlier were now the undefeated, undisputed champions.

"We were intent on proving we could be Super Bowl champions," he says. "Along the way a wonderful thing happened - no-one ever woke us up. Next thing we knew we were undefeated!

"That still resonates in my mind today. We accomplished something that no other team has ever accomplished."

Jim Langer died on 29 August 2019, shortly after this interview was conducted. You can read his obituary here.