Mo Farah heads to London 2012 via Kenya

- Published

In the latest part of our #olympicthursday, external series on leading British Olympic hopes in the build-up to the Games, BBC chief sports writer Tom Fordyce profiles athlete Mo Farah.

Laid-back Farah unaware of Olympic schedule

Sometimes the life of an Olympic athlete might seem an easy one: Lottery funded, big-name endorsements, masseurs on call, nothing much to do all day but indulge your singular sporting talents.

Sometimes it seems a whole lot harder. How did Mo Farah tell his six-year-old daughter Rihanna he would be leaving the family home before Christmas for a training camp thousands of miles away, and would not be back for five weeks?

"I didn't have to say too much. She saw me packing my stuff, and she started crying. She said, 'You're not coming back, are you?' She knew I was going for a long time because I was packing so much stuff."

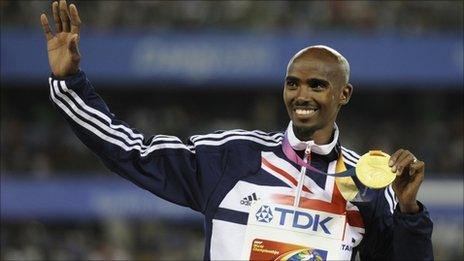

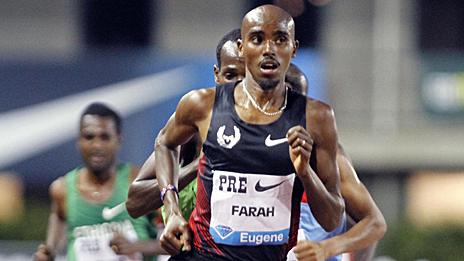

Farah, the first British male ever to win a global long-distance track title, is used to making sacrifices. His preparations for London 2012 are taking him a long way from that utopian ideal of the professional sporting life.

For the past month and a half he has been living a spartan existence high in Kenya's Rift Valley, eating like a local, sleeping like a local and running like a demon. You'd call it monastic, except monks generally have strong beer or fruit-based liquor to brew and enjoy, and almost never have to run 125 miles a week.

"I sleep in a basic room, no television, wake up in the morning, run, have breakfast, sleep, do gym in the afternoon and another run in the evening," he tells BBC Sport. "That's it. There are no other activities - no going to the cafe, no going for coffee."

Iten would be an unremarkable town of tin houses and red dusty roads if it were not for its extraordinary distance-running heritage. Perched 2,400 metres above sea level, it proudly displays a sign by the road in from Eldoret that says it all: "Home of champions".

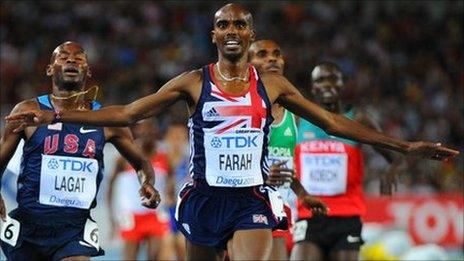

Fantastic Farah wins world gold

This is the area of Kenya that produced 81 of the 100 fastest marathon runners in 2011, including all of the top 20. For its altitude, endless miles of trail and rich distance heritage, it is almost impossible to beat, which is why Farah, Paula Radcliffe and the rest of Britain's best are based here at a training camp jointly funded by the London Marathon and UK Athletics.

Farah has been coming here for four years now, staying at a centre owned by former world half-marathon record-holder Lorna Kiplagat. It has not got any more sophisticated.

"It's very basic," he says. "You just eat, sleep, train. We eat lots of ugali - a maize porridge with loads of carbs - chicken for protein, spinach and rice. It's not like Nando's.

"It's a simple life with no distractions. At home you've got Christmas, New Year's Eve, all the people around you. Here you've got nothing. It's not easy leaving your family behind, but as an athlete that's what you have to do. I have to go and make it count.

"It's going to be hard. I want to be close to my family and be with them, but I have to train. And to be the best, that's what you've got to do. I have to work harder."

Farah's first experience of the east-African way came back in 2006, when his agent Ricky Simms suggested he take a room that was going spare in a Kenyan house-share in Teddington. "They just trained, ate, slept, trained, nothing else. I just thought, 'Wow.'"

It was the start of Farah's conversion from talented but wayward tyro into world champion.

"It got results. If you want to compete against these guys and beat these guys, you've got to learn from them. I'm lucky to be training with them.

"As an athlete I'll do whatever it takes to get close to a medal, to become Olympic champion. You have no choice. If you want to be the best you have to do that. Wake up in the morning, go for a run - it becomes a normal thing. There aren't any mornings when you wake up and think, 'I don't feel like going for a run today'."

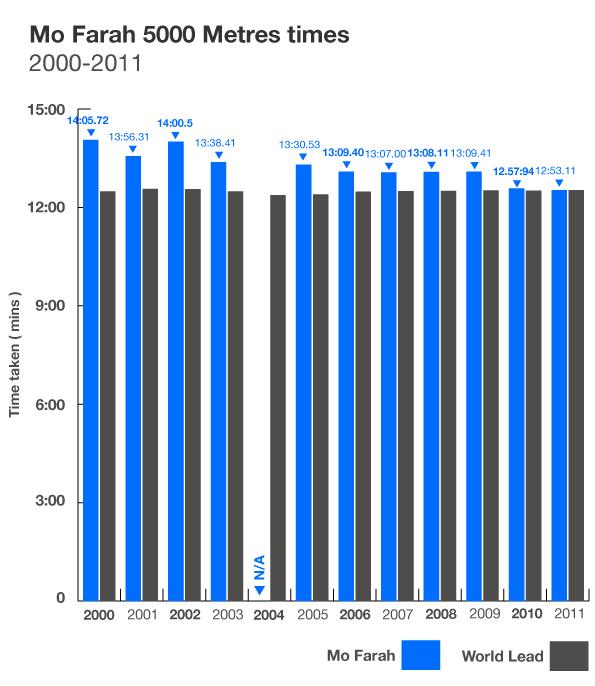

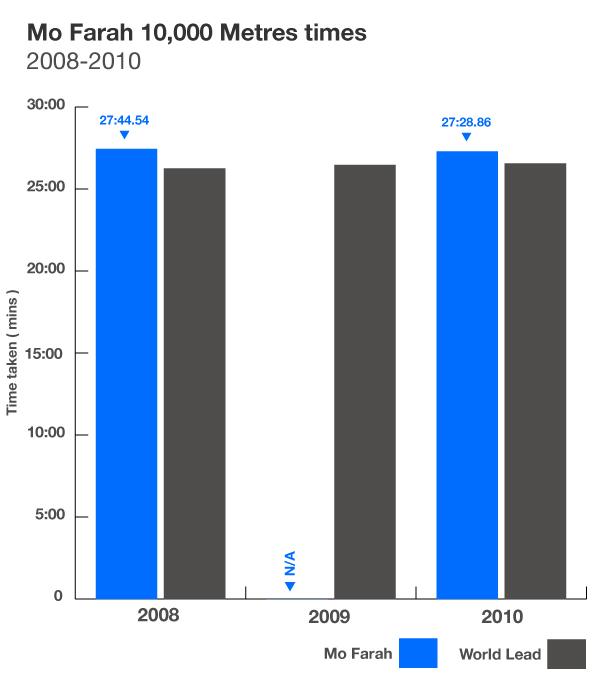

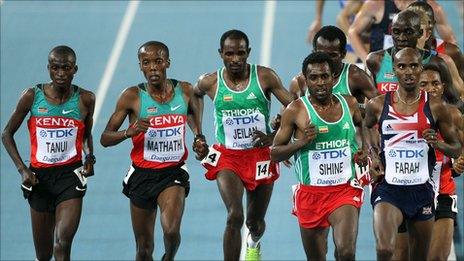

It might be hard, but it's effective. If Farah's 5,000m gold and 10,000m silver at last summer's World Championships in Daegu confirmed his status, the comments of his former mentor Radcliffe offer another endorsement.

"My relationship with Mo has changed," says the woman who once paid for the youthful Farah's driving lessons so he could get to training. "He's now an inspiration to me."

Kenyan athletes won 17 medals in endurance events at the Worlds in Daegu. Farah is no longer intimidated.

"If you train with them, mentally you think, 'I can compete with these guys, I know how they do what they do'. It makes you feel stronger. It's like if you're in a football team and you've played with someone before - you know what that player is capable of. It's doing your homework.

"They've shown over the years that they're the best in the world by far, but we've shown that we can compete against them. We can mix in. The mentality is changing now. We can do what they do. We can make it count too."

On Saturday, Farah will make his first competitive appearance in this most important of years, running the 1500m at the Aviva International Match in Glasgow. He will then have a crack at the British two-mile indoor record at the Birmingham Grand Prix on 18 February before taking aim at the World Indoors 3,000m title in Istanbul.

A year ago his demolition of the British and European indoor 5,000m records at the Aviva Grand Prix set him on the road to that global outdoor title seven months later. The plan, like the lifestyle, is simple: let's do the same again.

- Published4 September 2011

- Published18 January 2012

- Published28 October 2011

- Published5 October 2011

- Published4 September 2011

- Published28 August 2011

- Published4 June 2011

- Published19 January 2012

- Published12 January 2012

- Published1 January 2012

- Published10 September 2015