East Germany athletes were 'chemical field tests'

- Published

- comments

They talk of stolen childhoods and long-term health traded in for medals, of dissenters bundled into wooden crates and young women growing up to look and speak like men.

The history of doping in athletics has no more haunting chapter than the one covering the era of global dominance by East Germany. The well-being of the country's youth was sacrificed in the name of glory and propaganda - and still the scars are being healed.

To mark the 30th anniversary of the first World Athletics Championships in Helsinki, where the East Germans finished top of the medals table, BBC Radio 5 live has been to Germany to hear harrowing testimony from those who once were silenced and now want to shout.

In Helsinki, athletes bedecked in the blue and white of the GDR won 22 medals, including 10 golds. From 1976, across a period of just over a decade, East Germany won more medals than any other nation at three Olympic Games and two World Championships.

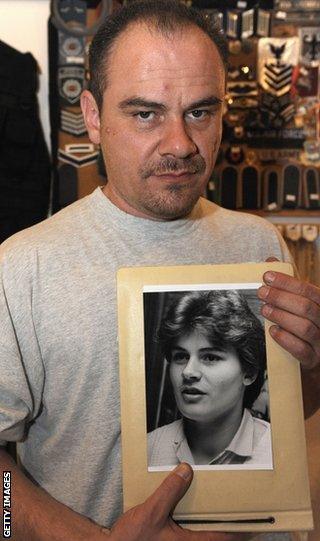

Andreas Krieger with a picture of himself as a woman (Heidi) in 1987

"We were a large experiment, a big chemical field test," says Ines Geipel (pictured at the top of this article), a former world record holder in the women's sprint relay.

"The old men in the regime used these young girls for their sick ambition. They knew the mini-country absolutely had to be the greatest in the world. That's sick. It's a stolen childhood."

The fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989 exposed the depth and extremities of the systematic doping programme on the eastern side of the bricks and barbed wire.

"It originated for one reason, that was national importance," according to Professor Werner Franke, a fearless campaigner who gained access to many files belonging to the Stasi, the secret police, and uncovered the sins of the past.

"Annually, about 2,000 athletes were added to the programme. We know this very exactly because there have been many court cases with all the details. The youngest athletes were around 12 or 13. And it was not just pills, injections also."

The Stasi kept hidden files on all international athletes. In some cases, athletes and coaches were spying on each other. Geipel's file contained more gruesome details than most.

In 1984, at a training camp in Mexico, she fell in love with a local athlete and made plans to flee East Germany to study and "start a whole new life" in the United States. She returned home to break the news to her boyfriend, only for him to reveal he was in the secret police.

At that stage, the full power and authority of the "machine" came bearing down on Geipel. At her home in Berlin, she told me of a plot that belongs in one of the novels she now writes.

"Firstly, they wanted to find a man in the GDR who looked like the Mexican I'd fallen in love with," she explained. "They thought if I met a man who looked like the Mexican, then everything would be good again. There wasn't such a man.

"Then they tried to force me to commit to the Stasi. But I didn't do it.

"The last stage was that they didn't see any other option than to operate on me and cut through my stomach.

"It's all in the files... they cut the stomach in such a way, through all the muscles and everything, so that I couldn't run any more and didn't have a way of getting to the rest of the world any more.

"The plan started with the sentence: 'She is to be strategically extinguished.' That's Stasi speak. It means she's to be thrown out of the sport."

In another file, Geipel remembers reading about the system in place at the 1972 Olympic Games in Munich.

"There the Stasi had built wooden crates, like rabbit crates, in hotel rooms," she said. "If they believed an athlete was going to flee - because the Games were in West Germany - they would put this athlete in the crate and carry them back to the GDR.

"I find it so symbolic. We were objects, we weren't people."

Geipel is now president of a group called Help for Victims of Doping, explaining that her sadness and pain have been converted into action.

It is believed that as many as 10,000 athletes were part of the programme. The drug of choice was Oral-Turninabol, a steroid targeted particularly at young females because the effects were more dramatic, at a time when women's sport internationally was under-developed and therefore ripe for domination.

In 2000, 32 women filed a lawsuit against the perpetrators and the court in Berlin heard tales of woe regarding hearts, livers, kidneys and reproductive organs, with mothers blaming the disability of their children on the wrecking ball of drugs.

One of the plaintiffs was Andreas Krieger, who represented East Germany as Heidi Krieger in the mid-1970s and underwent a sex-change operation two decades later.

I visited Krieger in Magdeburg, where he now lives and finds it hard to conceal his resentment.

"I still say today that they killed Heidi," he said. "Through administering these pills to me, Heidi was killed and she's not there any more.

"It's difficult to say whether I would be Heidi today or not but I could have decided on my own. That decision was taken away from me. And Mrs Geipel put it this way... I was thrown out of my gender."

Like many others, Krieger was enrolled in the programme as a teenager.

"In our country, we had an economy lacking many things, like fruit," he continued. "So we were told we were taking vitamin pills that would compensate for our lack of nutrition. They played God with us back then."

A compensation fund of £2.5m was set up by the unified German government and the Berlin court case ended with suspended sentences for the head of the East German Sports Ministry, Manfred Ewald, and the chief doctor, Manfred Hoeppner.

More than 300 athletes were each awarded around 10,000 euros (£8,500, $13,000). Thousands more failed to come forward to stake a claim. For some, there was lingering embarrassment, for others a reluctance to relive the agony.

State Plan 14.25 was responsible for many victories at the world's great sporting events. For an impoverished, inward-looking nation, the meticulous and wide-ranging policy left a huge dent in the national budget. The cost in human terms is impossible to measure.

A crime against humanity?

"That's the least it was," concluded Professor Franke.

You can listen again to the BBC Radio 5 live special, 'The Record Fakers' on the BBC iPlayer or by clicking here.

- Attribution

- Published16 November 2012